Search

You searched for contributors, issues and articles tagged with Sustainability ...

Contributors

Issues

Articles

“Look at that: you made it”

Alanna Okun, The Curse of the Boyfriend Sweater.

I learned to sew as a young child. Sitting in my mother’s lap, I picked up the delicate and confident touch and precision to snip threads and manipulate cloth as she made clothes for herself, my sister and me. Before I could read and write, I was adept at using a needle and thread to form my creative visions in the three-dimensional materiality of cloth. Mum taught me to cut, alter and mend to make efficient use of materials and garments, a make-do-and-mend sensibility that she learned from her own mother, raised during the Depression in rural South Australia. At my mother’s side, I also came to understand and express my sartorial sensibility and identity through the garments I made. Mine is a common story.

“Beauty is a curse and I’ve got it.”

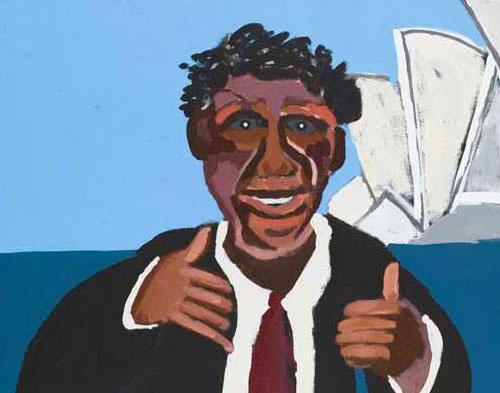

Effie is the most beloved character from the 1989 Australian TV sitcom Acropolis Now, which is set in a fictional café of the same name. Her character is a defiant assertion of “wog” ways: her high hair and incessant gum-chewing are flamboyant stereotypes, but her character, and those of her castmates, were then new to Australian TV. Acropolis Now, a spin-off from the highly successful stage play Wogs out of Work, dislodged the Anglo-centric narratives of Australian comedy TV. The show has been credited with popularising the term “skippy” or “skip”, used by Greek, Italian and other non-Anglo Australians to refer to Anglo-Celtic Australians since the 1970s.

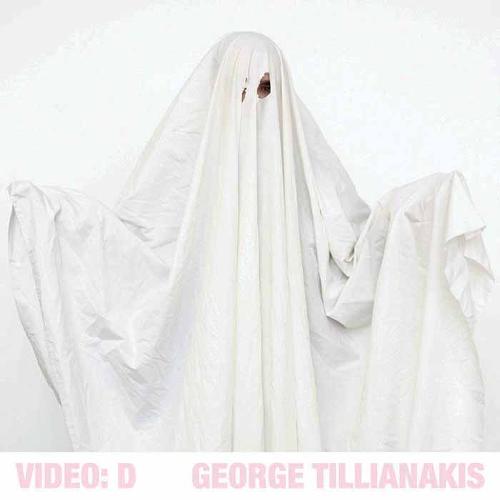

How do you haunt a ghost?

For the most part, this is not a rhetorical question because, simply put, a ghost can’t be haunted: it is the medium of haunting itself. The space-time paradigm of the terrestrial won’t allow for it. Haunting, as conceived in the vernacular imagination, demarcates an activity reserved solely for “the unhallowed dead of the modern project”, those improperly buried inheritors and victims of repressed, unresolved violence and injury—those whose lives were stalled and silenced. So by virtue of this logical impasse, you can’t technically haunt a ghost.

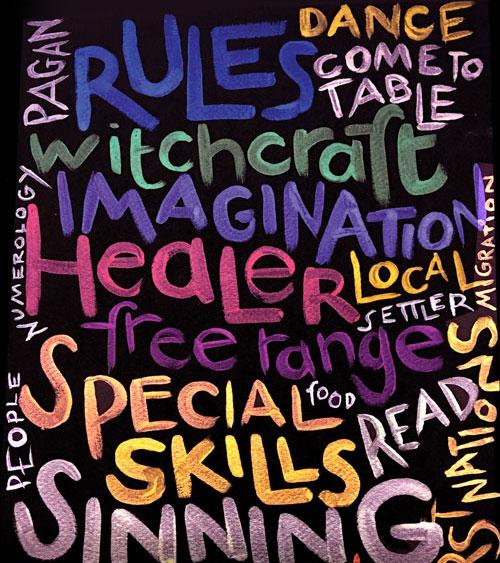

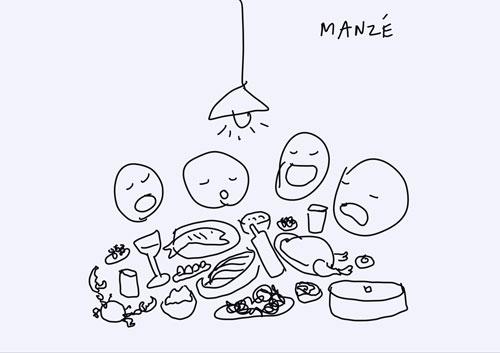

In 1906 Alfred Henry Lewis famously stated in Cosmopolitan that “there are only nine meals between mankind and anarchy.” Food has the capacity to bring us together. It is familiar, relational and cultural. But in times of conflict and scarcity, food also can be the trigger for chaos and social disruption. In a world with increasing and unprecedented ecological degradation and economic inequality in the distribution of resources, future food security is a global concern and a food fight to avoid. We are distracted, choking and bloated on choice and misinformation when it comes to food and health (our own and that of the planet).

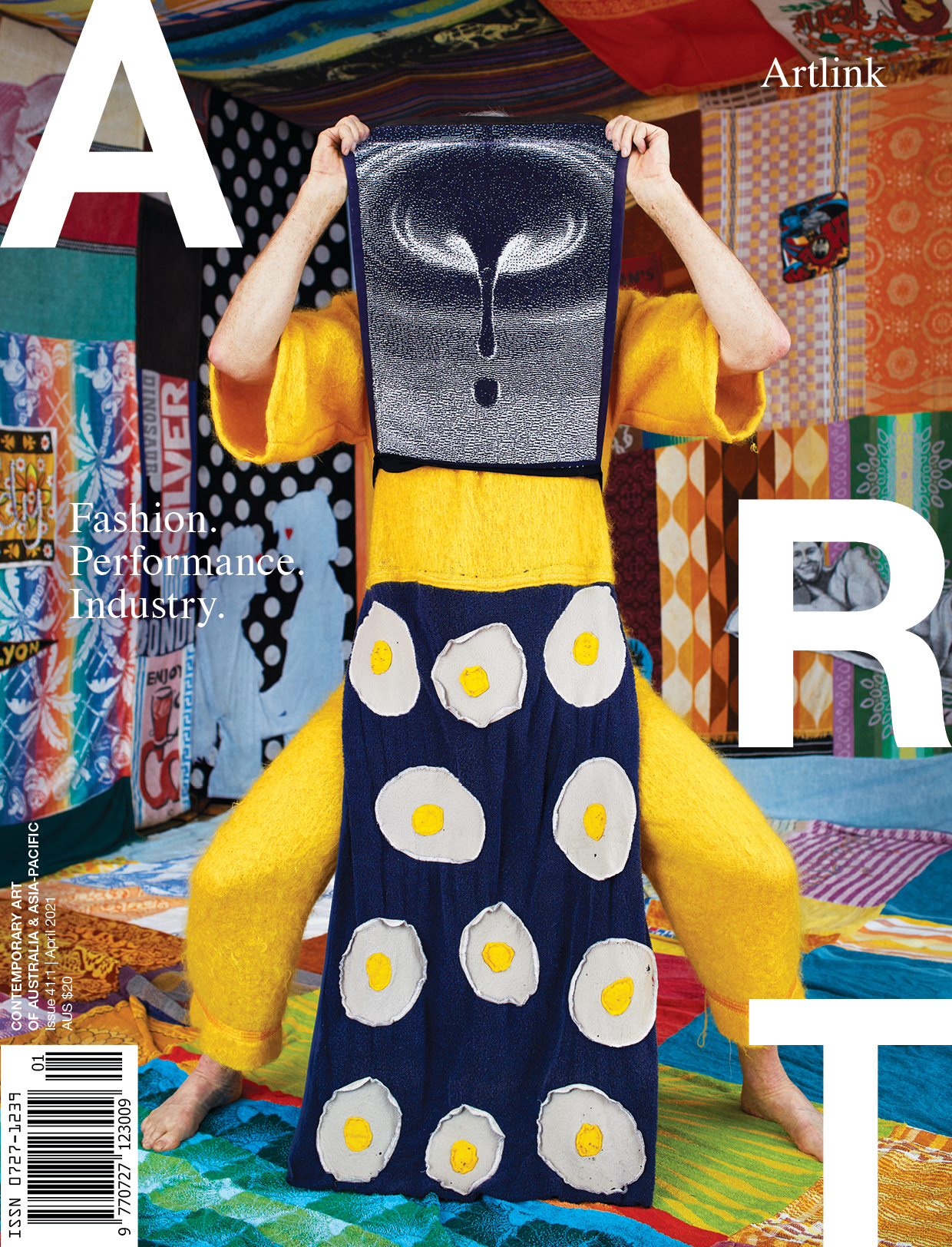

When art meets food, their offspring are often surreal. One need only look back to the ubiquitous presence in kitchens world-wide of reproductions of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s fruity portraits or René Magritte’s iconic green apple to find triggers for this impulse.

The relationship between food and art has long dominated the world of painting, photography, literature and cinema in an often-noxious pairing of gratuitous ingestion and aesthetics, most notably in Marco Ferreri’s The Grande Bouffe (1975) and Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, The Wife and His Lover (1989).

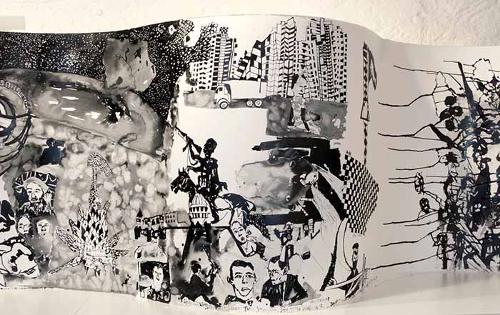

In conversation with Sabrina Baker

In recent years, I have worked alongside Jason Phu on a number of projects, notably My Parents Met at the Fish Market commissioned for West Space in 2017. This professional relationship became a friendship, with Jason often staying with my partner and chef Nagesh Seethiah and I on his frequent trips to Melbourne. Almost every visit would become a conversation over dinner about life, politics, family, careers, love and of course food. These are also recurring topics in Jason’s art practice.

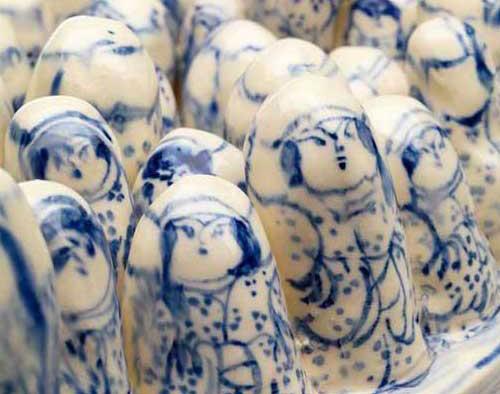

I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china.

Oscar Wilde, 1874

As an aesthete Wilde surrounded himself with beautiful objects. This epigram from his Oxford days paid tribute to and satirised the Victorian craze for the exotic. At Oxford University Wilde was introduced to the culture of aesthetes by art critic and philanthropist John Ruskin whose writings on craft also influenced William Morris.

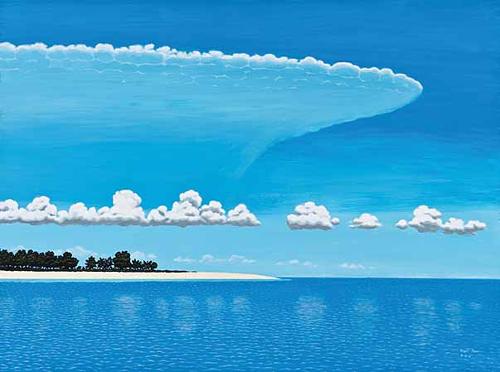

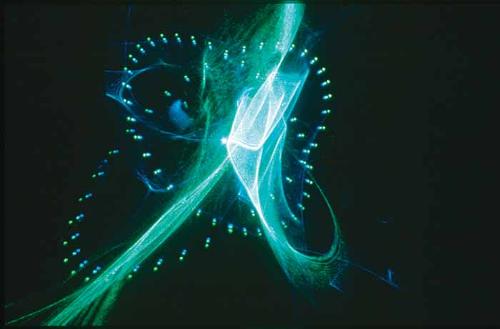

Wardlipari is the homeriver in the Milky Way.

Purlirna kardlarna ngadluku miyurnaku yaintya tikkiarna.

The stars are the fires of people living there. Yurarlu yurakauwi trruku-ana padninthi Wardlipari.

Yurakauwi the rainbow serpent goes into the dark spots in the Milky Way.

Ngaiyirda karralika kawingka tikainga yara kumarninthi.

When the outer world and the sky connect with the water the two become one.

Eve Sullivan interviews Lisa Slade Curator of the 2016 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Magic Object

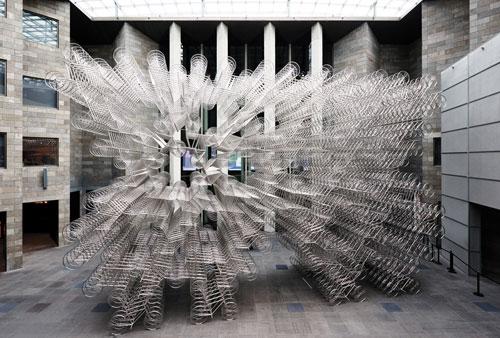

One of the centrepieces of Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei at the National Gallery of Victoria is a fresh iteration of Ai’s Forever sculpture. Located in the foyer, the sculpture consists of a towering arch of over 1,500 interconnected bicycles, all uniformly produced to a minimalist design. The Forever series is now among Ai’s most known works, having been exhibited in many configurations in museums and public spaces in London, Taiwan, Taipei, Venice and Toronto and elsewhere. The namesake is China’s Yong Jiu (which translates as“Forever”) brand of bicycle. Established in the 1940s, the prized Forever brand dominated China’s cycling culture for several decades before the car became more widely used. For Ai there is a tainted nostalgia about the Forever bicycle. In the remote village where he was raised after his father – an enlightened and popular poet – was exiled from Beijing, the bicycle was not only needed for travel but for transporting things. It was also out of reach to all but the well-off, a high status object of intense desire for a child like Ai living in poverty.

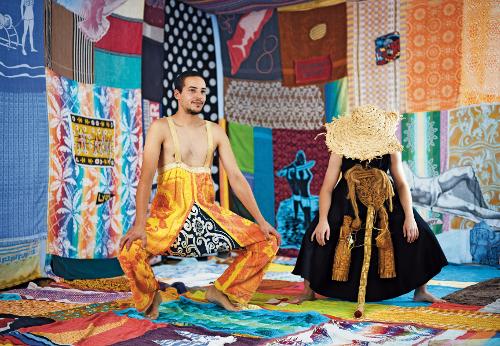

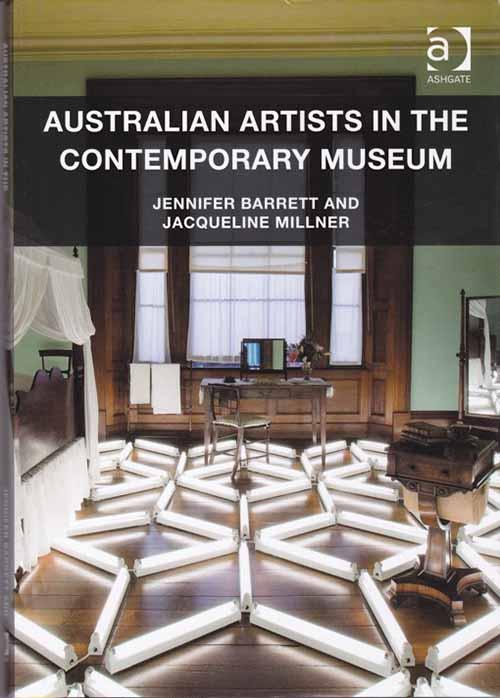

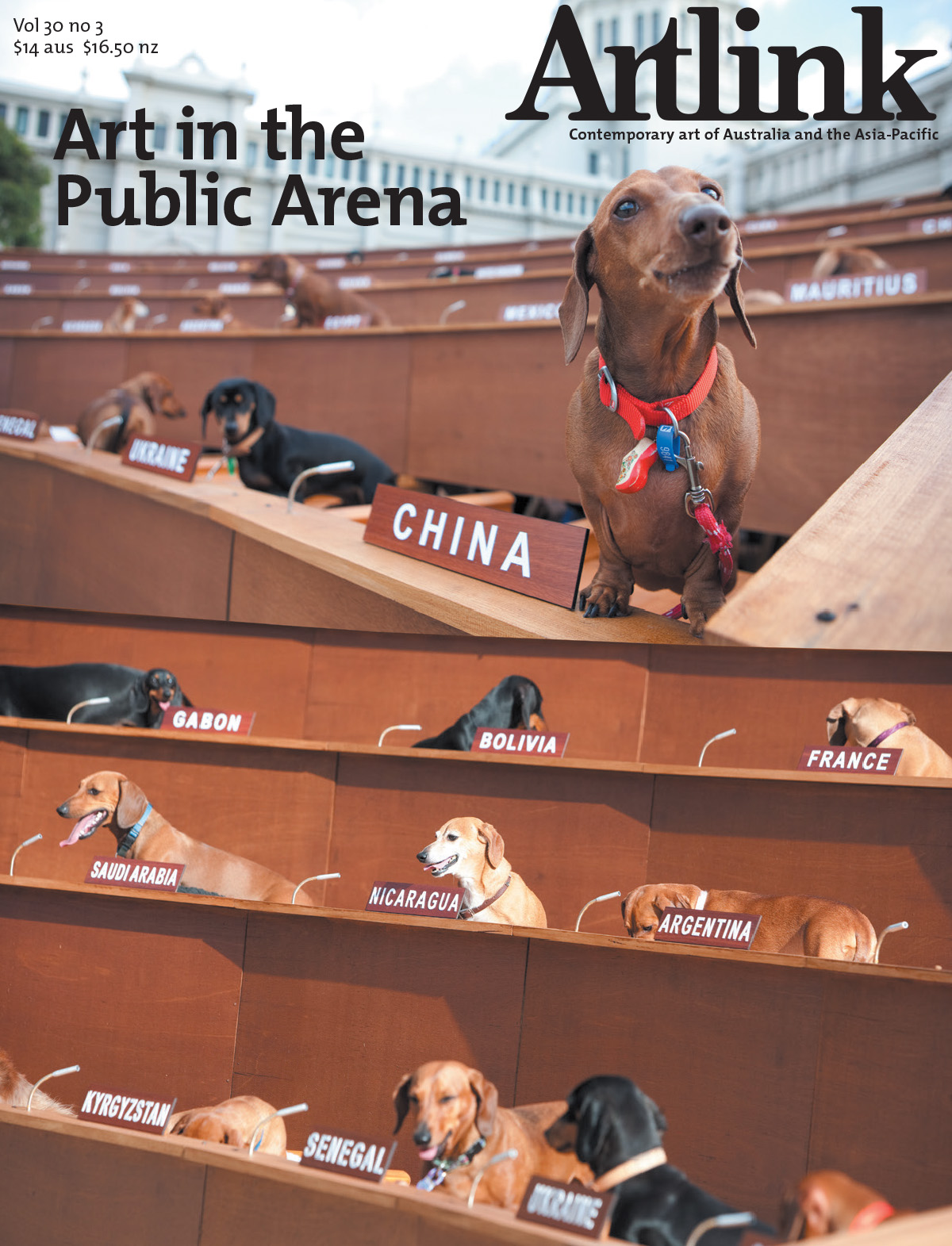

Much of the discourse around contemporary art in the last twenty years has been about the social turn, a catch-all for collaborative, conversational and relational practices of one kind or another. Claire Bishop has argued that much of this discourse is not about art at all, but ethics. She says that social practices should not be mistaken for ethical practices, comparing the art gallery dinners of Rirkrit Tiravanija to Santiago Sierra’s tattooed Mexican junkies, and the community outreach of Oda Projesi to Jeremy Deller’s re-enactment of a miner’s strike protest in Britain. Here an ethical debate turns into a political one, as Bishop finds an analogy for social conflict in Deller and Sierra, in the way that their work does not carry a clear social message but enacts an ambivalence that suspends ethical judgement.

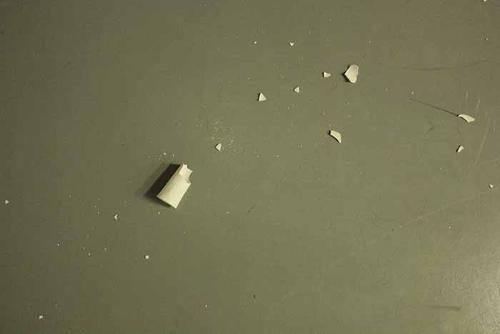

Ceramics has always been about the sticky materiality of clay. Unlike other mediums where the material is often the passage for the artistic idea or vision, the medium itself drives the concept. This gooey, organic substance has for thousands of years been crafted into a myriad of forms and textures. Recently, we’ve been hearing of a “revival” or “rediscovery” but potters and ceramicists have always engaged critically with their material – challenging form, pushing technical boundaries, experimenting with the baffling chemistry of glazes, subverting embodied narratives – in an attempt to understand their material. Over the last decade the field of ceramics has expanded to incorporate those that work with clay, rather than just those that were trained in clay, and along with it a flow of critical thinking and collaboration in art, craft and design is blossoming, driven by the possibilities of new artistic materials, and the need to find sustainable solutions for those already in use.

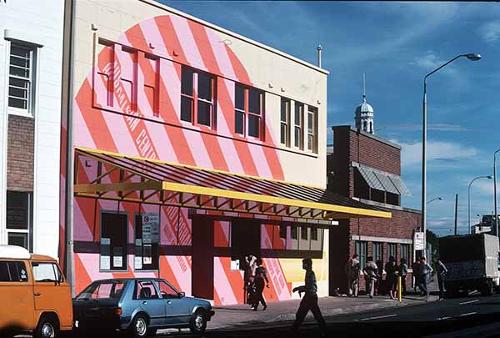

Sometimes my life as an artist feels a little fraudulent. For twenty years I worked and still work as a curator although I was trained as a painter. No art administration for me! I am an artist. So I always felt a little fraudulent as a curator as well. When I left university I wanted desperately to be an artist. Living and working in Wollongong did not present many options so we created them ourselves. In 1995, along with Lisa Havilah and Nathan Clarke, we opened Project Contemporary Art Space. About a year later I started working with Guy Warren at the University of Wollongong. Then that’s it for the artists’ life for nearly the next twenty years.

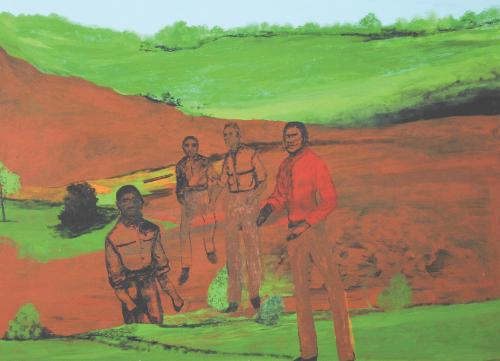

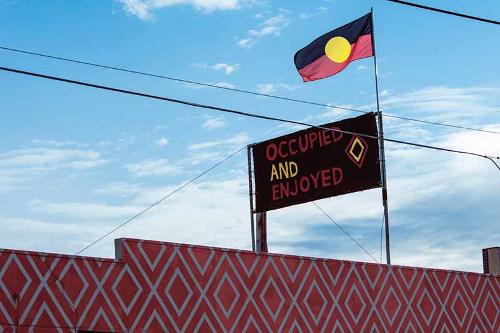

Art, performance, and spoken or now written text, all belong to the same register of cultural practice in the First Nations I am familiar with or belong to: ceremony. This ceremonial register takes place in a set of spaces created to enact cultural responsibilities to place, people and balance. Galleries and museums, as sites of cultural production and presentation, have the potential to nurture new ceremonies and new working methods.

Lucy Bleach quietly moved mountains in 2015. Based in Hobart, for a number of years her work has used the language of geology to explore volatility, impact and resonance. By slowing down the experience of these forces, the slow flux of her artworks present opportunities for intimate encounter and reflection. Increasingly, her innate sculptural sensibility has also brought these concerns to an expanded field of sites, communities and histories, generating collaborative projects that engage people in deeply felt, transformative processes. Last year saw these concerns blossom in a series of five major projects, that collectively identify her as one of the most exciting, dynamic and significant artists operating in Tasmania today.

Eve Sullivan in conversation with Fontanelle directors Brigid Noone and Ben Leslie

The founding father of independent Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, famously lectured his citizens that “Life is a marathon” (without a finish line), encouraging them to work towards long-term rather than to sprint to short-term goals, not only for the individual but more so for the state. His life’s achievement came to an end on the 23rd of March this year; but his son, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, subsequently realised one of the citystate’s long-term goals when he launched the National Gallery Singapore (NGS) on 23 November 2015.