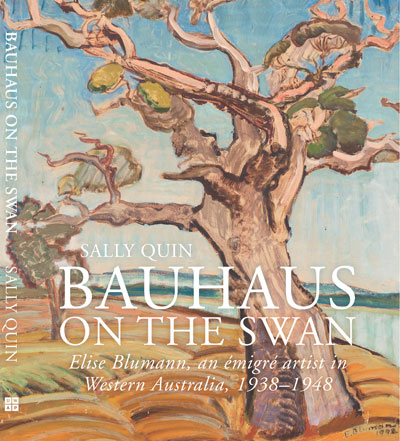

In Bauhaus On The Swan: Elise Blumann, an émigré artist in Western Australia, 1938–1948, Sally Quin tells the story of Prussian-born Elise Blumann, one of Australia’s most important women modernists. After fleeing Nazi Germany with her newborn second child, a diamond ring and smuggled cash in her baby’s bassinet, the artist is reunited with her husband and first-born son, and in 1938 settles in Perth on the banks of the majestic Swan River. She had spent her early years studying in Berlin and worked in proximity to the avant-garde developments such as Die Sturm, Die Aktion and Der Blaue Reiter group, and became the first artist to undertake a sustained engagement with the Western Australian landscape in modernist pictorial terms, remaining particularly committed to pursuing an introspective, utopian form of expressionism.

The obvious question is: why did she move to Perth, so distant from central Europe? The reason was both poetic and pragmatic. It was not Western Australia’s renown mineral resources, but extracts from Australian eucalyptus oil that prompted the artist’s industrial chemist husband to accept a new position in Perth. This same essence would infiltrate his wife’s work in which the eucalyptus melaleuca became a recurring and inspiring motif.

Carefully avoiding the clichés of the émigré story, Quin writes a focused biography that charts Blumann’s significant achievements from her arrival in Perth until leaving for Germany in early 1949 and simultaneously touches on attitudes to modernism and the influence of local culture on European refugees and émigrés newly arrived in the city. Unsuitable to position within the standard framework of Western Australian modernist art history, we enter her artistic realm through her own individual vision within a broader context of radical local literary circles. We learn that Australian cities were not ready for her Weimar expressive impulse when she exhibited for the first time in Perth in 1944 and later in Melbourne. Yet, working in isolation and with little critical support, the artist produced a remarkably progressive body of work.

This beautifully designed book is the first major monograph to be written on Elise Blumann and rightfully places her at the forefront of Perth modernism. Nicely titled and well-illustrated with supplementary family and social milieu photographs of the period, this narrative makes an important contribution to our understanding of Blumann’s role in the development of Western Australian modernism and situates her within the history of the modern movement nationally.