Fashion Performance Industry—three words in parallel alignment express the modes in which fashion can be experienced in the world. Undeniably, the act of dressing, of selecting the clothes we wear on our bodies, inextricably intertwines us in performances of who we are across matrices of culture, race, gender, sexuality and class. The adage that clothes make the person, attributed to great men of pre-feminist eras (Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Mark Twain), asserts a connectedness between dress, identity and performance that has since been scrutinised from feminist, queer, Indigenous, cultural, postcolonialist and contemporary forms of “otherness”. But, as Judith Butler famously wrote in 1993, it’s bodies that matter. Every act of putting on clothes is an individually coded performance of a particular body.

Industry, the back-end processes of making, sourcing and supplying garments, has more recently been shamed into the limelight. Under ethical pressures over worsening conditions for labour and major pollution issues, the fashion industry has had to become accountable, with activist groups like Fashion Revolution and consumers alike no longer dazzled by the front end of the runway. And, to counter combinations of poor land management practice and negative effects of climate change, there has never been a greater need to develop ecologically friendly sustainable fibres.

Loosely divided under those broad categorisations, this edition was developed with Eve Sullivan, as Artlink executive editor. A positioning essay by Adam Geczy puts fashion at the epicentre of identity politics and performance in global art debates, while also answering the question of the “why” of fashion in art—why fashion retains its hold of centuries. Reading across dynamic folds of East and West, Geczy’s examination of transorientalism also unpacks the condition of our global present in the works of Rei Kawakubo, Cao Fei, Lindy Lee, Blak Douglas and Shirin Neshat.

On the home ground of country, at Ngukurr in the Northern Territory, Tristen Harwood negotiates “the rakish vernacular of Indigenous style” in presenting a history of “minor rebellions, comportment, respectability, and the phantom histories of Indigenous lifeworlds elaborated through dress”. In a stunning analysis of a set of juxtaposed images—a photograph of a young woman in a creased skirt leaning against a truck, a painting in which the outline of a group of stockmen only just resists their absorption into the ground, and a colour photograph of a dapper Ginger Riley Munduwalawala—Harwood sketches the “radical acts” of disorder through which they “stake a claim on a metaphysics of dispossession”. Indeed, elements of this ongoing dispossession are highlighted in his opening remarks, where he draws an important distinction between “Indigenous style”—what people in community actually wear—and what has been produced as “Indigenous fashion” under the “multi-sited, asymmetrical power dynamics and labour conditions that constitute global fashion design”. Recent community-driven fashion initiatives are radically shifting the ground, with Indigenous elders and artists setting the terms of engagement.

Belinda Cook unpacks the story behind the innovative vision of elders Eva Nargoodah and Tommy May, trust in the cultural authority of artists, and how a partnership of equals developed with Melbourne designer Lisa Gorman in the hugely successful Mangkaja x Gorman collection. Cook also underlines what this has meant to community, reflecting that “while the Indigenous art sector continues to put Indigenous artists on the map globally, fashion serves a purpose that is almost more potent as it infiltrates the very mode in which we identify ourselves. It enables Indigenous artists to wear their art, to wear the country passed down through generations, to proudly show their connection in the very cloth they are wrapped in.”

In a conversation with her mother Peggy Griffiths-Madij and with Alana Hunt, Jan Griffiths affirms the significance of Peggy’s award-winning “Legacy Dress” after it took out the Cultural Adornment and Wearable Art Award in the inaugural National Indigenous Fashion Awards. “That one dress for Mum is like bringing all the textiles from the girls together, with the stories that got handed down to them, and stories from Mum and their elders. Textiles are another way of putting our stories into art, again. It’s not a canvas, or a cave, or the sand, it’s now on the material of the fashion world, our story on people’s bodies, to carry on that story.”

Loosely grouped under the rubric of performance, four diverse artists challenge sartorial stereotypes and recode mainstream dress. Paying homage to drag culture in Cigdem Aydemir’s lip-synced performance of Madonna’s Like A Prayer, Sumaiya Muyeen explores femme ecstasy as a queer feminist aesthetic for women who choose the veil.

Melanie Jame Wolf calls out toxic masculinity in her deconstructive performance practices and wears her male targets as costumes in drag. Analysing Wolf’s nightclub and strip-joint performances of Acts of Improbable Genius and MIRA FUCHS, Daniel Mudie Cunningham draws out the correlations between labour, intimacy and gendered economies of desire. The discursive space/time of night and the shape-shifting power of three-minute pop songs are tracked through Oh Yeah Tonight. The disruptions of hetero-normative clichés extend to Michaela Stark’s self-portrait photographs as a bound grotesque, bulging under the discipline of pink satin bindings. Through conversation with the artist, Alison Kubler reflects on the pairing of the pretty and the abhorrent.

Through analysis of Sarah Rodigari’s Effie T-shirts, Abigail Moncrieff navigates “aspirational modes of normality” in second-generation migrants and negotiates Rodigari’s redressing of the vernacular in her performances of filibustering activism.

In respect of industry, no encounter with contemporary fashion can ignore the consequences of the overproduction of Fast Fashion. Many major fashion companies, including the likes of Zara and H&M, not only produce too many collections a year, but produce such quantities of cheap, poor-quality, highly disposable fashion that the planet’s landfill and waste-disposal systems are struggling to cope. The statistics that Dana Thomas presents in her book Fashionopolis are staggering, with a sixth of the world’s workers employed in clothing manufacture yet less than 2% of garment makers earning a living wage. The clothing industry is responsible for 20% of industrial water pollution and 10% of global greenhouse emissions.

It doesn’t stop there. More than 60% of garments contain fabrics derived from fossil fuels. Polyester, ubiquitous in cotton blends, is basically a plastic byproduct of the petroleum industry. Should the world manage to free itself from fossil fuels, it will hopefully also free itself from plastics. Currently up to 35% of the plastic pollution in the oceans comes from plastic particles washed off synthetic clothes. Cotton itself has become an offender, with its overproduction responsible for drying out the Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth largest lake. Given these statistics, organisations such as Fashion Revolution have put themselves at the forefront of the pressure for change, demanding ethically produced clothes from fibres that are environmentally sustainable.

Madeleine Seys is part of this consumer rebellion, sewing her own clothes under the moniker of #IMakeMyClothes, an affiliate of Fashion Revolution. In her multi-layered essay, she presents an insider view of the maker revolution and the broader collective agency of her community of home sewers.

In the field of textiles, innovations in green chemistry have been key to advances in wearable marine biopolymers sourced from seaweed, one of the most sustainable and renewable resources on the planet. Based in South Australia, where prolific quantities of seaweed grow along the coast, artist researcher Niki Sperou is well placed to discuss her collaboration with the Centre for Marine Bioproducts Development, at Flinders University, under the title “Green Plastics – Blue Ocean”.

Environmentally, the carelessness of human action has led to unforeseen extinctions and invasions of introduced species. I am drawn to include reference to artist Christine McMillan and the extraordinarily delicate dress she sequined with carp scales from a fish retrieved during an environmental river clean-up. An introduced species, carp is a notorious bottom feeder that muddies the water to the detriment and near-extinction of many native fish. The fragile-looking garment is in fact extraordinarily tough—the carp scales had to be pierced with an electric drill to be serviceable. Furthermore, that airy web of thread holding the carp scales together is plastic fishing line, making the garment doubly environmentally unfriendly. The contradictions in analogous human behaviour are in evidence here: we carry on creating beautiful, spectacular items of dress from products that have proven catastrophic for the planet.

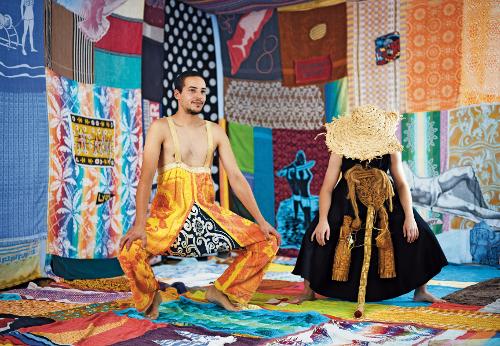

On this point of responsible action, Rachel Buckeridge’s Dadaist creations for Circumnavigate Kandos in our clothes have been grouped with industry for their strategic and ethical resonance with global maker movements. Through her use of materials sourced from street throw-outs and second-hand pieces from op-shops, her absurdist humour is underscored by a salvage ethos.

Lastly, rounding out the edition is Michaela Gleave’s Cosmic Time, a costumed performance for four percussionists. With a theme extending all the way back to the big bang and the formation of the planets, through to the evolutions of biology and consciousness, her contemporary allegory charts the history and ontology of the universe in a radical decentring of human importance from a universe-centric approach. Dressing her musicians as spirits of the multiverse (a hypothetical group of parallel universes that comprises everything that exists: the entirety of space, time, matter, energy, information, and the physical laws and constants that describe them), she rethinks our conceptions of the universe through the codes of dress.