Since its inception over twenty years ago in 1993, the Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) has played a key role in the reimagining of the region’s cartography. Born in the Paul Keating days when the significance of the region was framed by economic policy, the APT has worked tirelessly to constantly reimagine the region away from the originally US-defined rubric. Through the lens of art as a political, social and cultural driver, the region’s boundaries have been stretched, tested and extended to now include countries such as Georgia, Dubai, Mongolia, Nepal and the Kyrgyz Republic.

Each APT has recalibrated the region’s boundaries, flows and agenda. The APT functions to reinvent the region from within; it does so by curators travelling to different countries and visiting studios to uncover new ways in which artists are working in the region. In this way, the APT marries art to ethnography in new ways. Now consisting of an APT Conference, APT Kids, APT Cinema and APT Live, the APT deploys various frames to rethink the region as an entanglement of different and shifting localities. APT8 consists of more than 80 artists and groups from 30 different countries.

Given the twenty years of iterative processes it is no surprise that APT8 focuses upon performance and the body. Here the theme becomes a metaphor for the region’s shifting identities and cartographies. While the theme could be reminiscent of early 1990s feminist poststructuralism, APT8 manages to bring new light to the body theme through non-Western explorations of texture and affect. Here the work of Sara Ahmed is evoked, particularly her publication The Cultural Politics of Emotion (2004) in which she argues we must move away from traditional Western binaries of emotion as inside/outside but rather as a force that resides in the texture and on the surface of the skin. It is through the role of performative texture and affect that the Asia-Pacific cartography is giving new light.

.jpg)

The significance of texture and skin in the exhibition can be read as an antidote to current Anthropocene critiques arising from climate change and global warming debates. As new media scholar and curator Joanna Zylinska put it, the Anthropocene is “a geo-historical period, in which humans are said to have become the biggest threat to life on earth”[1]. So how can we (the Anthropocene) redeem itself? APT8 seems to provide multiple pathways, ideologies and visualisations of humans in and within the environment that suggests hope in a time of great uncertainty.

Textures on and in and around skins feature throughout APT8. In a period where “skin” has been colonised by videogame vernacular creativity it is interesting to note how little new media figures here. The exceptions are the performance works by Filipino Australian Justin Shoulder and Bhenji Ra (with the mobile phone playing music) and the Vietnamese UuDam Tran Nguyen’s online multi-player crayon car drawing. The only area that seems to fully engage with the quotidian, uneven and all-pervasiveness of media like mobile phones is APTCinema.

.jpg)

Curated by Jóse Da Silva, APTCinema consists of three strands that all explored differently the texture of the visual – “Pop Islam”, “Filipino Indie” and the work of Lav Diaz. Co-curated by Khaled Sabsabi “Pop Islam” explores the manifestation of Islam as popular culture and mobility through the lens of visual media. “Filipino Indie”, co-curated by Yason Banal, harnesses the powerful role of everyday media like mobile phones and YouTube to bring new playfulness around do-it-yourself (DIY) reappropriations of cinema tropes. Consisting of a screening program and a video work by Banal, “Filipino Indie” highlights the deployment of vernacular, creolising and playfulness particular to the Philippines. This is complemented by Lav Diaz’s more sombre and historical approach to cinema to comment upon social, religious and governmental shifts in the Philippines.

While it is a success on many levels, it’s a shame more of this new media discussion wasn’t incorporated more generally across APT8, rather than being relegated to the job of cinema, especially considering the increasingly powerful role new media plays in the social, political and cultural transformations in the region. Moreover, given the paradoxical role of new media through the powerful and uneven role of ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) in terms of the region’s consumption and production, it is surprising that there were not more works investigating waste in and around media technologies as both generating “meaning, but also detritus and disease”[2]. Artists such as Ravi Agarwal, Yao Lu and Tattfoo Tan are obvious examples of this intervention into quotidian media paradoxes to provide alternative media solutions or reflections.

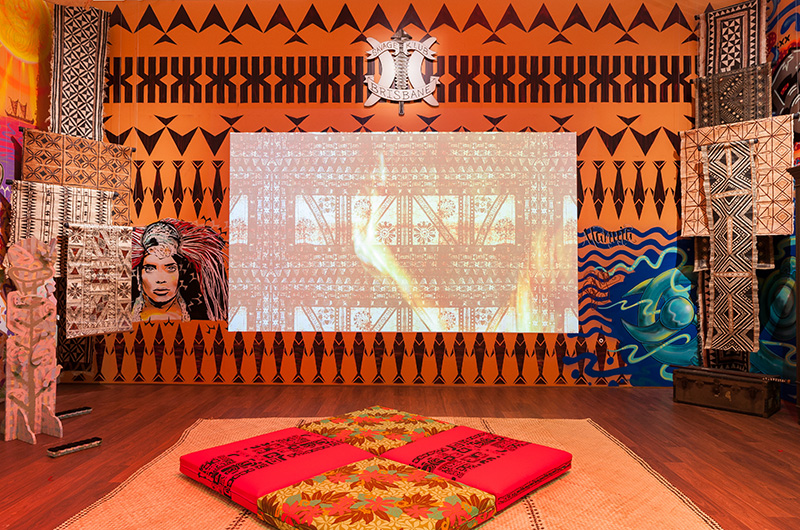

Skin as a texture and affect can be found from Justin Shoulders’ visceral performative green dragon made from balloons and various shiny waste materials to Cambodian Anida Yoeu Ali’s roaming 10-metre long The Buddhist Bug. The role of the environment and the body is heightened in works from the Aotearoa; especially Rosanna Raymond’s two interactive installations and Shigeyuki (Yuki) Kihara’s haunting skins of her colonial spectres. Raymond’s Play with Your Birds features vernacular patterns (tiputa) made from barkcloth (tapa) made for dance and ceremonies is here repurposed as rubbings onto the paper and worn as shirts. The SaVAge K’lub is Raymond’s reworking of the gentlemen’s club as a site for Polynesian reinvention through hybridised Colonial and Máori costumes as performative skins. Kihara’s photographs of herself dressed in Colonial costumes highlight the role of photography to comment on power and death.

The role of photography to comment on spectres and hauntings between human presence, history and the land is continued in the photographic work of Japanese artist Shiga Lieko. The photographs for RASEN KAIGAN (Spiral Coast) were taken from 2008–12 around Kitakama, a town completely decimated by the tsunami of 2011. In these photographs the human presence haunts the land, just as the spectres of the natural disaster linger.

The skin of capitalism continues to the surface in South Korean artist Choi Jeong Hwa’s evocative The Mandala of Flowers. Here the Anthropocene waste has been transformed into a magical and whimsical site of play. Through the appropriation of colourful bottle tops and lids, e-waste becomes aesthetic play. Adults and children could be found sorting and building patterns in both meditative and frenetic ways. Choi’s work seemed to also comment on not only the power of art to reinvent waste but also the overkill of mindfulness colouring books as people in capitalist countries seek increasingly to focus upon wellbeing in an age of quantified self.

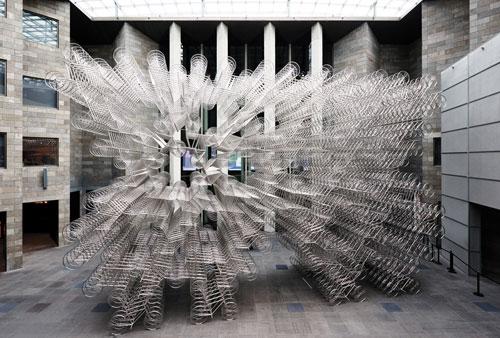

Tensions in and around the body as a site for Anthropocene questioning can be found through various works. In particular, Indigenous Australian Yolngu artist Gunybi Ganambarr’s work in which he shifts from bark painting to discarded thick rubber mats left from conveyor belts at mine sites in the Yolngu lands. Transforming everyday waste into art is inverted in the work of Iranian artists Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian, who use other artists’ works and found objects in a recreated studio. Every centimetre of space of the floors and walls is covered and adorned. It presents the everyday as a site for global reinvention and celebration.

It is the APTKids section that the most curious reworkings of the Anthropocene can be found. Not that the children participating are thinking about the anthropocene! However, it is in this space that the most interactive and playful interventions are located. From Shoulder’s and Ra’s Club Anak (Club Child) by Shoulder and Ra to Nguyen’s aforementioned Draw 2 Connect with License 2 Draw and Yelena Vorobyeva and Viktor Vorobyeva’s reinvention of fruit in I Prefer, the plethora of playful options in APTkids are more than mere child’s games. Hetain Patel’s Behind the Mask consisted of a series of photographs (and video) of children dressed as their favourite superheroes; this was extended to include children in the gallery space who could also dress up and join the digital display. What APTKids highlights is that when play comes to the forefront, art can operate in powerful ways to reimagine our relationship – to the body, others and the land. Perhaps those debating the Anthropocene should look to APTkids to see the pathways artists and audiences are offering to transform waste into art and, in turn, help to reshape our region for sustainable futures.

.jpg)

Footnotes