.jpg)

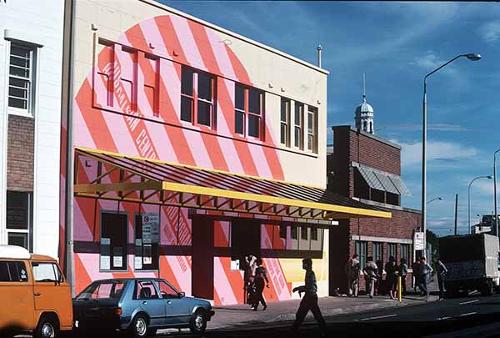

To say that I'm still troubled by curator Mark Feary’s On Return and What Remains nearly ten days after first experiencing it, is perhaps the highest compliment I can give. Complex, unsettling and remarkably nuanced given the usual dogma that surrounds any typical discussion of war; the exhibition is, in many ways, the ultimate portrait of the problematics of modern warfare.

It explores first-hand experiences of war as well as the complications of its aftermath. Its timing, coinciding as it does with the centenary of World War I, is not accidental. In fact, this context really only amps up the pervading sense of unease provoked by this carefully curated series of meditations on the manners and consequences of war today. Any notion of the nobility or heroism or righteousness that earmarked so many young men’s experiences and motivations 100 years ago is well and truly absent from this video game generation. Almost as a matter of course, six of the ten works shown here are film or video-based pieces and the slipperiness between real and virtual, imagined and experienced, is occasionally scarily literal.

Richard Mosse, whose devastating portrait of beauty and horror in the Congo was shown at the Irish Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, shows several works, created during his time as a photojournalist embedded with US forces in Iraq in 2008-09. KillCam (2008) interweaves, with chilling casualness, leaked combat footage of US soldiers killing alleged Iraqi insurgents with footage of amputee and wounded Iraq veterans at a US convalescent hospital participating in a video game tournament.

Baden Pailthorpe’s multi-channel work is a trippy, shiny, fucked up, almost Disney-fied comment on military technology and unmanned drones. In MQ-9 Reaper (That Others May Die), strange objects, like shipping containers, float malevolently against a kaleidoscopic bright blue sky, their walls opening to reveal putting greens, living rooms and zombified men going idly about their hobbies, while grim reaper flags flutter in the breeze.

Elsewhere, Bonita Ely and Harun Farocki explore PTSD and notions of reconstruction. In her sculptural pieces, Ely literally reconstructs furniture from her childhood home – beds and sewing machines – into a malevolent watchtower and machine gun; a reflection on the impact her father’s return from WWII had on their domestic space.

In his film Immersion, the third instalment in the late artist’s Serious Games collection, Farocki examines the experimental use of virtual re-enactment by the US military to help treat returned soldiers suffering from PTSD. To call this vicious loop of technology – from training to therapy to entertainment – ironic is to seriously underplay the clinical disturbance of these virtual worlds in the first place.

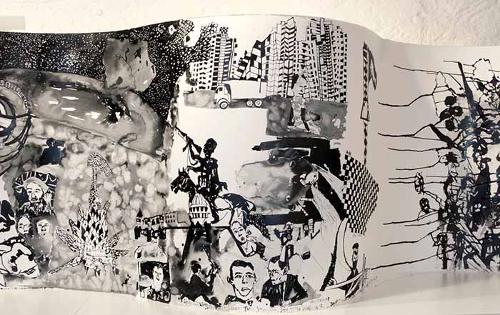

Works by filmmaker Omer Fast and current Artspace resident Khadim Ali also feature in the exhibition. Fast is his usual dark and disturbingly absurd self with the strangely mesmerising Continuity while Ali’s beautiful rug and his gouache paper works sadly get a bit lost amid the noise and movement of the surrounding video pieces. Despite this, it is a cohesive and incredibly considered exhibition, while being strategically disconcerting. God help us all.