How many photographs did Vivian Maier take? Some written reports say 80,000, others 100,000, 120,000 and even up to 150,000. I'm commencing with numbers, because the appearance and global dissemination of Maier’s work, recently discovered and brought to the public gaze, is manifestly tied to numbers in the context of her archival emergence into the public domain of photography. This unintentional gift of a life and life’s work is a freak of reincarnation, documentation and mysterious indifference, demonstrated through oppositions of private exhibitionism and voyeurism combined with compulsive narcissism and abject self-erasure.

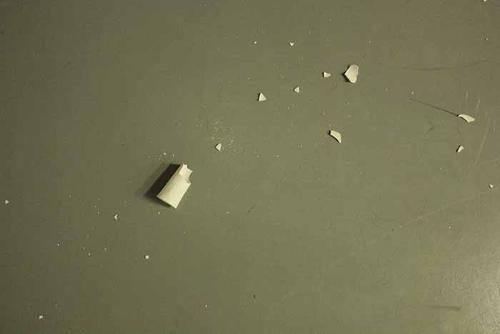

The exhibition of selected images of Maier’s work at the CCP gives a clear sense of what she desired and what gave her pleasure. Some comment on the functional 'click’ of the camera lens and ‘click’ as a means of philosophical self-confirmation: I photograph, therefore I am. This may have been a visual way of being and permitting herself to be part of an outer world that she found difficult to communicate with. Her self-portraits are astonishing in compositional originality; her eye in looking for material layers often found an infinite mirror of progression that is both humorous and metaphysically abstract. Her personal expression in self-portraits is not so much dour, as is often stated, but the face of concentration and blatant self- enquiry, honest above all. Naomi Cass, Louise Neri and Karra Rees, the curators of Crossing Paths with Vivian Maier, selected nine other artists to be included in this exhibition: Cherine Fahd, Gabriella and Silvana Mangano, Debra Phillips, Patrick Pound, Clare Rae, Simone Slee, David Wadelton and Kellie Wells. Their photographic and media practices, in their own terms, refer to identity, or ambiguation and concealment of identity, as both self-portrait, or as a kind of insertion of self into place and time. Most overtly, Patrick Pound and David Wadelton have worked in the domain of the ‘found’: Pound, in finding and re-presenting anonymous personal photographs as an archival sampling of the personal meeting the photographic; and Wadelton, as a long time photographer of a very specific Melbourne suburban commercial and domestic architecture that has a before and after of almost 40 years. Simone Slee obliviates and yet marks her absence in her ‘self-portraits’. The Mangano sisters, along with Kellie Wells and Clare Rae, make duration and their engagement with it, a kind of instinctual dance that is moving as well as frozen. Debra Phillips and Cherine Fahd also move between the selection of markings and the secreted personal mark as evidence of presence and the obscured.

The idea of a contemporary photography enquiry and relationship to Maiers’ work through the work of the other nine photographic artists was a good one but it did point out an epic abyss of time between Maiers and the impact of photography history, theory, and institutional education on contemporary practices. That abyss is partly to do with complex differences between practices but also the dramatic difference between nostalgia and photography in our current understanding and reception of the then and the now.