Late last year Donald Brook died in Adelaide at the age of ninety-one. To those of us who were lucky enough to have worked alongside him and witnessed the scale of his contribution to Australian art, the loss is beyond measure.

The sense of loss is not sentiment. Donald was an unusually acute thinker – a philosopher who was also a gifted artist; possessed of a complex, often contrary spirit that was realised in both his expressions of love for and dislike of, the institutional aspects of the art world.

There was never any doubt about the intense, focused intelligence Donald brought to each aspect of his multiple contributions to the field, shaped by his laser-sharp critical responses and his indomitable energy. Donald was a force to be reckoned with, his influence is profound, but his gift of “shape-shifting” is also what defines the mercurial nature of his legacy.

Throughout his life, he was highly regarded in many roles: as a sculptor, philosopher, teacher, writer, scholar, instigator, creator, facilitator and mentor.

He was born an only child into a very poor family in Leeds, which he later described as, “A cultural wasteland of lower middle-class environment where artistic ambitions persisting into maturity were taken as evidence of insanity.”[1]

In a bid to appease his parents’ anxiety about his future earning capacity, Donald began his tertiary education in electrical engineering, although from an early age he only wanted to make sculpture.

He was conscripted towards the end of the second world war and benefited from the free post-war university training offered to ex-servicemen, choosing to go to art school at the University of Durham, the only university art school that had a sculpture course at that time. Donald got to know Henry Moore as the external examiner of his degree work and was awarded a travelling scholarship to the British School in Athens.

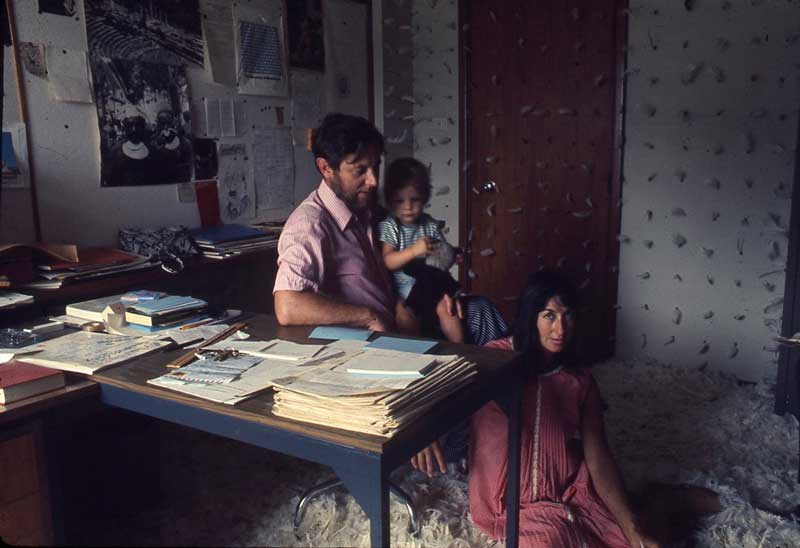

Instead of attending classes he wandered around Crete looking at his favourite Cycladic art, and drawing. Optimistically he went to Paris to be a starving artist. Back in London, he worked for a firm that made props for the film industry, and later for a group making public sculpture commissions for companies. He met and married Phyllis who was a dancer and shortly after applied for a teaching job at a university in northern Nigeria where his friend the British studio potter Michael Cardew was doing important work in the field. Donald headed the sculpture department there for two years, introducing a new emphasis on the arts of Africa but fell foul of the hierarchy over a matter of principle.

Returning to London, he had a solo exhibition which was much admired by John Berger. He was awarded a place in the Digswell Arts Trust, a studio complex sponsored by industry. Finally he had a studio to call his own, but the problem of an income proved insuperable. One day Phyllis saw an advertisement from the Australian National University inviting applications in PhD research studies in the humanities.

“I wrote to John Passmore who was professor of philosophy at the ANU, whose name was in the advertisement, and said I would like to spend three years just thinking about what I was doing. And he said, ‘What are your qualifications?’, so I sent him some of my writings, unpublished philosophical writings about the visual arts, and he seemed very happy with that. He wrote back immediately saying the university would be happy to have me.” Donald arrived in Canberra in 1962.

His research was to consider some fundamental questions about the visual arts world as it was currently regarded, raising questions about how art is appraised and understood, in particular photography and sculpture. Were judgements about contemporary art all really just as flimsy as fashions in clothes or marketing? His supervisor was Bruce Benjamin and the Brooks became close friends with the Benjamins over many years.

Keen to continue making sculpture, he was taken up by Max Hutchison and exhibited at Gallery A in Sydney and put on a small stipend. He was the art critic for the Canberra Times and judged the Mildura Sculpture Prize in 1967. But the five years of thinking and writing and making work (which suited him very well in many ways) came to an end, and he was still short of an income.

When the brand-new Power Institute was established in Sydney he took up a position as a senior lecturer working under the Director, Bernard Smith, who had come from Melbourne University: “… he wanted to make the Power Institute into a European art history department, and he rationalised doing this on the grounds that this was the only way to secure international academic respectability for the Power Institute. His test for whether we were succeeding was to be – he said this explicitly – whether our graduates would be accepted for post-graduate work in European art history at the Courtauld.”

Donald’s interests were diametrically opposed to this notion.

“I had no doubt that I could introduce theory and philosophy of art as well, because it obviously made sense to do that, but it made no sense to Bernard and, indeed, in the end, when I developed philosophy courses expecting to generate some theory of art, I was forced by Bernard to teach them, with David Armstrong’s consent, in the department of philosophy. They… were made available to the Power Institute students, you know, as a concession, but they weren’t officially part of the Power Institute’s teaching.”

“There was then the issue of getting some connection between art history and theory teaching and the practice of visual arts, and I had always believed that an art school should be in a university because that had been my own experience … although I disagreed with everybody, it did seem to me that it was the best environment. There were people thinking at these places about philosophy and history … There was serious research and sciences going on. I believed that universities were the place to put artists. I don’t know if I believe this anymore but, at the time, I was a great advocate of this.”

During this time Donald also worked as the art critic for the Sydney Morning Herald. But his practice as a sculptor had stopped. “I began to think I just liked making things and there is no particular reason why they should be sculptures … I convinced myself that works of art have no logical or intrinsic relation to art, to the concept of art. Works of art are just objects with a function within a certain branch of the entertainment industry… Art is something else. Art is concerned with memetic innovation.”

In line with this he and Marr Grounds founded the now legendary Tin Sheds, an informal venue on campus (and officially for students to explore the materials and methods of the old masters). The reality was that Bert Flugelman, David Saunders and Marr Grounds encouraged arts, architecture, engineering students and anyone who turned up, including Noel Sheridan and Tim Burns to dream up and make and do things of all descriptions. There were very early experiments with computer graphics and the group Optronic Kinetics emerged, creating some of the first environments and interventions.

That year (1968) Clement Greenberg was invited by Bernard Smith to give the inaugural Power Lecture: “… he brought Greenberg out thinking that this would be a fashionable contemporary touch to his own platform of art history, and also it would please one branch, at least, of the notional Sydney avant-garde, the New York school people … [Greenberg] was failing by then. His dominance was really over in America. It’s just that they didn’t know in Australia that it was all over… he wasn’t a fool by any means, he was just wrong, but he wasn’t a fool and he had quite a lively mind and he looked around and he thought that the most interesting stuff, if you were just going shopping in Australia, was the local mythography, the kangaroos, rats and stuff like that … He found what was going on here, apart from the mainstream modernism, was this ‘Antipodean’ art that was really ‘quaint’.”

Bernard Smith invited Donald to give the second Power Lecture in 1969. This was at a time of extraordinary personal upheaval for Donald and Phyllis after the kidnapping and murder of their first child, an event of momentous impact on the course of both their lives. The opportunity was a welcome distraction for Donald and it was obvious to him that it had to be a response to Greenberg.

The lecture, called Flight from the Object, introduced the term Post-object art, and was eventually recognised for the watershed that it was. But at the time, despite a huge audience including all the notable artists, critics, theorists, academics, there was total silence in the commentariat. Donald’s distinction between art and works of art – a major plank of his propositions – was neither debated, nor dismissed; a veil of baffled silence descended. His assertion that the closest we can get to understanding the meaning of the word “art” is to define it as memetic innovation, the engine of cultural evolution, was not something that resonated with the art world at that time, which simply ignored it and continued as before.

Donald’s iconoclastic spirit had no truck with the fine arts dogma determining that real works of art have “aesthetic quality”. He rejected this notion on the grounds of its subjective nature. Aesthetic quality was certainly not the currency at the Tin Sheds. It was clear that cultural shifts were being explored, including innovations in science and technology – electronics, sonics, image-making, communications, computer science. It was in fact a 24/7 experimental lab. The Sheds continued to operate for many years and were an important seeding ground for a vast range of challenging political art practice.

After five years at the Power Institute, the disagreements between Donald and Bernard over how courses should be taught and works of international art acquired for the Power Bequest collection of contemporary art became intense.

“I was trying to point people in the direction that they absolutely didn’t want to go. They wanted either to go along roughly the path that Bernard pointed towards of Antipodean mythography, the establishment of an Australian identity, a figurative expressionism, all of that. That was one direction. And the other was New York, American internationalism, and I believed that neither of these was the right way to go … to think seriously about what art is, never mind whether it’s Australian or not, and never mind whether it’s currently fashionable in New York. But hardly anybody wanted to think like that. Some of the artists did but the authorities didn’t. The university didn’t, the educational authorities didn’t, the galleries didn’t. There wasn’t any money in it, you know.”

Donald applied for the inaugural Chair in Fine Arts at Flinders University and in 1974 he arrived in Adelaide ready to take on a new challenge.

One of the first things he did was change the name of the department from Fine Arts to Visual Arts. Flinders was a new university and there was scope to guide the course in a very different direction, offering a wide range of rigorous study programs across the visual arts. Lecturers were recruited from perceptual psychology, Indigenous cultures and archaeology, European art history and semiotics; post-graduates were free to investigate subjects of their choice.

Janet Maughan under the guidance of Vincent Megaw did primary research in the very early days of Western Desert art culminating in Dot & Circle the ground-breaking exhibition; Western Desert painters were invited to visit the art studio, a first for them and for the students. In 1975 Donald invited Tim Burns, famous for his work with explosives at the Tin Sheds and the Mildura Sculpture Triennial, to be an artist in residence at Flinders where his exploding videotape event was held to the considerable alarm of the university. These were heady days.

Two of Donald’s close friends and colleagues at Sydney University joined him in Adelaide to help shape the progressive new agendas – Bert Flugelman to run the Sculpture Dept at the SA School of Art and David Saunders to head up Architecture at the University of Adelaide. Early friendships with Ian North, photographer and curator at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Clifford Frith, Senior Lecturer at the South Australia School of Art, and Richard Llewellyn who had a small art gallery in North Adelaide, provided willing accomplices for the instigation, in 1974 on a blazing mid-summer day at Henley Beach, of the Experimental Art Foundation. Soon the group had secured an Australia Council grant, premises in the basement of the old Jam Factory in St Peters, and the first Director, Noel Sheridan, a poet, conceptual artist and legendary man in green, who was previously Head of the Dublin School of Art.

“Noel was a lovely man, clever, and understood very well what it was all about and what was needed and he had, as I didn’t, great social skills and a wonderful personality and people liked him and were easily persuaded by him. He could sell things but, if I tried, I could alienate people, so he was just marvellous.”

The EAF became the first “alternative art space” in Australia, and a template for those that followed. A succession of international visiting artists and theorists were part of a distinct sub-culture operating within a free-wheeling structure that rapidly built into a vortex spilling out across the country. Innovators were able to test their theories, including Jim Cowley placing fake billboards with inscrutable messages outside newsagencies, Stelarc’s cancelled suspension piece that became a cause célèbre or Stuart Brisley making a 24-hour performance at the end of which Noel threw a white then a black bucket of paint over his naked body. Most of these events went unnoticed by the general public even though as the art critic for The News I devoted a significant percentage of my columns to what was happening.

In 1992 Donald left Flinders and he and Phyllis went to live in Cyprus where they built a house. Later they moved to Perth where Noel Sheridan was running PICA and where Donald continued to write. In 2001 I invited him to give the Artlink Inaugural Annual Lecture, and the rapturous ovation which he received helped them to make the move back to Adelaide and to one of the first houses completed in the new Christie Walk eco-village in the middle of town.

Donald died in that house, where he and Phyllis had enjoyed many years of good company amidst the friendship of the wider arts community. He continued to write prolifically for art magazines and learned philosophical journals and in 2008, Artlink published his first book The Awful Truth About What Art Is, a short, funny and pithy summary of his theories, followed by Get a Life, a larger compilation of autobiographical pieces interspersed with his learned papers published in 2014.[2]

All who knew him are the poorer for losing such a remarkable and wonderful friend and colleague. His wit and wry humour were inimitable, and his willingness to speak out against unpalatable truths was something of a stock in trade that often got him into trouble. But Donald was never interested in easy comfort, and he maintained his brave interest in some of the deeper philosophical issues of our time to his very end.

Footnotes

- ^ This and all subsequent quoted extracts are from the interview conducted in 2011 for the Balnaves Foundation’s Australian Sculpture Archive at the Art Gallery of NSW by Senior Curator Deborah Edwards. I am much indebted to her and the Archive for permission to access and quote from this resource. The interview, made when Donald was 84 is a wonderful window onto his life and reveals more than anything his sense of humour and marvellous use of words. The unedited tapes are available from the archives of the Art Gallery of NSW: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/research/archives/interviews/

- ^ Both titles published by Artlink are available for purchase online at https://shop.artlink.com.au/collections/books. A comprehensive bibliography of Donald’s critical writing and response is published in Get a life: An autobiographical anthology of theories, Artlink, 2014, pp. 212–26.