Extending the theme devoted to life in the Anthropocene that was the extraordinary focus of the September issue on Bio Art (34#3), my first issue as editor of Artlink pays tribute to founding editor Stephanie Britton, whose vision and energy has sustained the magazine over more than three decades. Publishing 145 issues in a little over 33 years, Artlink is Stephanie's great legacy: a vast archive of developments, debate and coverage of the field of the visual arts, not a little of which was devoted to a keenly ecological way of thinking about the arts and the environment in this wide brown land.

Reflecting on the challenges of geography for Australian art and artists, I recently attended 'The Undiscovered’ symposium at the University of Western Australia, an initiative of Artsource, Perth. The collective lament, also in the face of many recent private gallery closures, was lack of opportunities for Perth-based artists to promote and show their work. The declining number of physical visitors to smaller galleries is indeed a notable development across the sector, as are the shifts in the market to bigger monopolies (like art fairs). (See the article in this issue by ex-gallery director, Damien Minton). But the implication that state galleries and national institutions are there to bail out artists (like failed banks) is clearly misguided.

At this forum, I was struck by the risk-averse attitude of the artists whose opinions were voiced, and of the need for artists themselves to think up new strategies and ways of working. Audiences don’t want to be ‘educated’ (as in dictated to) but they can be attracted, challenged and entertained by vibrant ideas, resonant fields and perspectives.

What would make the artworld and art more sustainable? This is a big question for creative producers. Clearly, the artworld is part of the problem as well as the solution, with our propensity to travel, high freight and production costs, leading to what Robert Nelson calls in his essay for this issue, our high ‘carbon plinth print’. Proposing ‘poetic solutions’ to validate an essentially aesthetic aim might seem modestly constrained, but it does acknowledge a role for art that is potentially more sustainable than grandiose posturing.

For those who want something more polemical, the end-stage predictions of complete social breakdown as a result of the accelerated effects of climate change, proposed with apparent relish by Ian Milliss, represent an alternative perspective. So, too, in the various art practices represented here, looking at resource re-use and recycling, big and little human landscapes, ideas of social engagement and mobility, I present to you a bounty of lively art interactions.

Sustainability, like feminism, is not an aesthetic that can be reduced to a merely representational or instructive viewpoint, like what might be more properly described as eco- or environmental art. Here, I am thinking of leadership projects like In-Habit: Project Another Country, by Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, focusing on the threatened livelihood of a minority group in the Philippines, and or the art coming out of Bimblebox Nature Refuge in Queensland as an action against the coal-mining interests of the state (profiled respectively in Artlink issues 32#3 and 33#4). So, too, as featured in this issue, Debbie Symons (like the late Stieg Larsson as corporate crime investigator) makes use of her skills in data research and visualisation to draw our attention to rates of species extinction (amongst the most devastating of threats), linked to our profligate lifestyle.

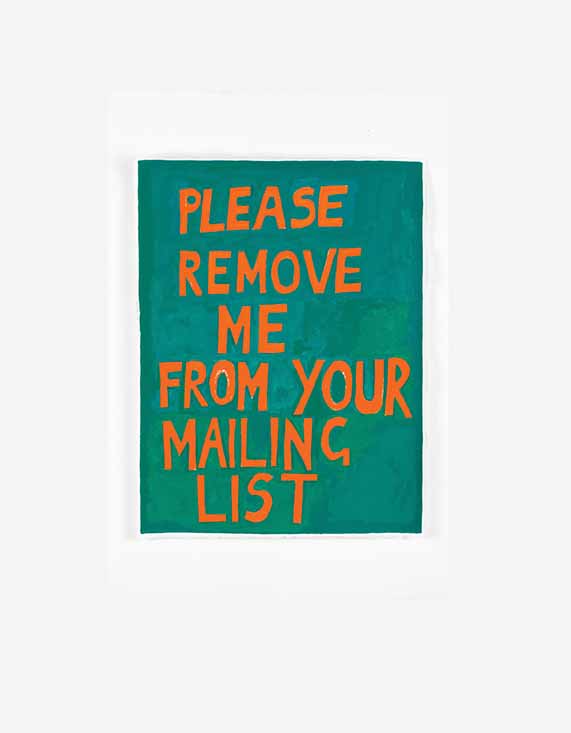

The case for art is rarely sustained by its literal message, as is evident, I hope, in the choice of artwork for the cover. This painting by Elizabeth Newman transforms the ‘environmentally friendly’ form letter into a wild act of defiant gesture. As she writes in her essay, there is much that is unsupportable and unsustainable in this world of ‘flabby pluralism’ and consensus without real choice. It is this inertia that is the real danger for humans.