.jpg)

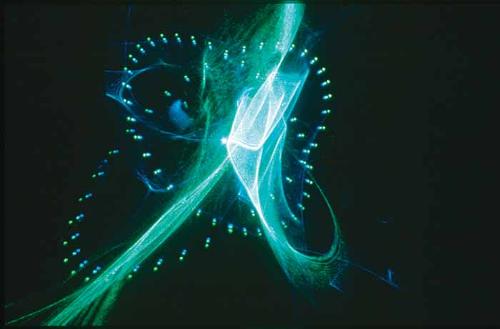

Video is superb in creating narrative, but it also constitutes a unique formal and spatial language. The recent exhibition at Griffith University Art Gallery LANDSEASKY: revisiting spatiality in video art drew attention to ways in which video investigates concepts and conditions of space in the moving image. Consisting of 20 artists from Europe, India and the Asia-Pacific, and spanning more than 40 years of art production since the early 1970s, LANDSEASKY also accentuated the global space of artists today. Artworks seemed self-reflexive, examining how a fundamental formalism inscribes a psychology of space, at the same time as they reached out and represented artists in conversation with the world around them, and each other. The exhibition as such brokers the kind of 'altermodernity' that Nicolas Bourriaud describes in his book, The Radicant (2009); a reconstruction of modernity that is specific to the present. Bourriaud’s most useful point is arguably that art now occupies a space more intent on exchanging ideas rather than imposing them. This era of ‘altermodernity’ only looks back to the extent that the past functions as a propellant through loops of change, ‘translating ideas, transcoding images, transplanting behaviours’.

Loops of change still need a compass and the point of coherence in this exhibition drew on the ways that video artists use the horizon motif as a perspective of space. This horizon line takes viewers on quite a ride because there is arguably no medium better placed than video to perform these acts of translating, transcoding, transplanting. Works from the Horizon (1970-71) series of short films by the iconic artist of moving-image minimalism, Jan Dibbets, set the tone in transcoding the horizon. Ocean horizons are doubled and redoubled in waves; cut, realigned, and reduced to their bare spatial essence. Wang Peng’s Feeling North Korea (2007) translates an experience of forbidden looking with footage of discreet film taken whilst walking in Pyongyang juxtaposed with a half-screen of black void. Wang Gongxin transplants the game of ping pong into a fascinating insight about how the synchronicity of sound and image (a ping pong ball travelling between three screens aligned with the sound of it hitting a table) incites our sensory perception of space to override the logic that differentiates real and virtual space in The Other Rule in Ping Pong (2014).

This touring exhibition also inhabits a global space literally. The curator of LANDSEASKY, Kim Machan, drew on her role and experience as Director of MAAP Space (Media Art Asia Pacific) to present the show in ten venues across Seoul, Shanghai, Sydney and Brisbane. She has collaborated with artists such as Wang Gongxin for over 20 years, giving her a sound base to work in a very innovative curatorial register. The Griffith University Art Gallery venue involved the full complement of participating artists across two ‘chapters’. The first included Jan Dibbets, Wang Peng, Wang Gongxin, Paul Bai, Yeondoo Jung, Shilpa Gupta, Yang Zhenzhong, Zhu Jia and Heimo Zobernig while Giovanni Ozzola and Yang Zhenzhong featured at MAAP Space in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley. The second chapter appears at Griffith University Art Gallery from 22 October to 13 November.