One of the most moving pieces in the 2014–16 Welcome to the Anthropocene exhibition at the Deutsche Museum in Munich was a sound recording of an extinct bird offered to the listener through a stainless-steel handpiece held to one ear. Above the device, a 19th-century illustration showed the lost New Zealand huia (Heteralocha acutirostris).

The idea of a vanished bird’s voice outliving its own demise thanks to the archival properties of sound-recording technologies is compelling enough. However, Julianne Lutz Warren and Matthew Young’s Extinct Birdsong — Huia Echoes (2012) is even more poignant and refracted than it first seems. [1]

The call is uttered by Maori tracker Henare Hamana, imitating the song of an imagined conversation between a female and a male huia feeding together in the forest. The species disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century due to over-hunting, land clearance and habitat loss. The recording was made in 1949 – meaning Hamana had held the bird’s voice in memory for more than four decades.

In turn, the original gramophone recording made by R.A.I. Bately, a European researcher in Aotearoa/New Zealand, is a repository for Hamana’s knowledge gleaned, perhaps, through what Bundjalung and Kullilli artist Daniel Browning calls “deep listening” (active, relational, ethical).[2] And in yet another turn, Warren and Young edited Bately’s “echo” of the huia to remove his narration for their own digital rendition, described as a “third echo of this bird-human-machine song”. A fourth echo occurred when the piece was performed at the People’s Climate March in New York City in 2014.

This complex system of traces resonates, too, with the Site & Sound exhibition held at McClelland Sculpture Park + Gallery, where something of the world itself – water flowing through landscapes, katabatic winds in the Antarctic, an empty glass bottle rolling along a pavement, human voices in the wake of a tsunami, a clicking dawn chorus of shrimps – is transmitted via its sonic residues.

Like Extinct Birdsong, these works are canny about their machinic assemblage. Across the exhibition, to greater or lesser extent, recorded sounds enter into what Indonesian sound artist Frans Ari Prasetyo calls “a complex relational dynamic with the environment from which they are taken”. [3] They are subjected to myriad transformations – distortion, reverberation, amplification, dissipation, composition with other sounds and instruments, dismantling and recomposition.

In an evocative description of the latter, Canadian composer Barry Truax’s work is explained as breaking sound into “grains” or “sonic fragments that are fractions of a millisecond, which are then manipulated to build up complex dynamic flows of sound, much like individual droplets of rain might together create a powerful flood”.[4] Ros Bandt, co-founder of the World Soundscape Project (1993–), is described as having used “granulated, stretched eagle calls to represent the orientation of the eagle looking down over the land” for her piece Raptor (2014).[5]

Rather than marking absence (extinction), though, works in Site & Sound hint instead at imminent loss and what gardens scholar Paul Gough refers to as future remembering.[6] As scientists identify 19 ecological systems currently under collapse in Australia alone,[7] and data modelling suggests that the world will taste its first experience of dangerous 1.5°C warming as early as 2024,[8] we listen “carefully and anxiously” to the world around us.[9] Sounds of cracking ice, or the “thick” soundfield of a remote Amazon rainforest teeming with species, conveyed in Lawrence English’s A Mirror Holds the Sky (2019), or even more “everyday” soundscapes such as bird choruses in David Chesworth’s Peron Station (2006) and Douglas Quin’s Madeira Soundscape (2013), take on extra resonance. They assume the air of future archives, seeming to chart and mourn a passing before it has even occurred.

Philosopher Danielle Celermajer describes a similar sensation as “anticipatory nostalgia”. When bushfire approached her home in the summer of 2019–20, she took a moment to sit inside at her window and write: “I look at them [garden, animals, bush and wildlife] as you can only look upon what you fear you may never see again. If I never see them again I will not be the same person.”[10] This is not “tragedy”, she argues – descended from capricious gods or indifferent nature – but disaster of human making, one in which we are all implicated and responsible.

Site & Sound offers an aural equivalent of acute attention to that which surrounds us, and which might soon slip away.

**

The exhibition is ambitious in scale. Curated by Jon Buckingham, Lawrence Harvey and Simon Lawrie, it draws together works from the RMIT Sonic Arts Collection (a unique initiative dedicated to acquiring, commissioning, presenting and promoting sound art in Australia), pieces held in artists’ personal collections and new commissions. The latter includes Madelynne Cornish’s audio-visual installation Borderlands (2020), created during a month-long residency at McClelland, which teases out aural and physical boundaries in the hybrid McClelland landscape.

Individual works range in length from around 10 minutes to an hour. When I meet curator Simon Lawrie at the McClelland Gallery, he tells me that it would take a full day for an “ideal listener” to absorb all the pieces in their entirety. “But I know that’s unlikely to happen,” he says. Instead, works can either be encountered by chance, in an eclectic, almost random smorgasbord of snatched sound; or particular items or suites of work can be selected from timed loops across several sites, in a more deliberate, dedicated and patient listening.

“The genre of sound art has a somewhat hidden history,” Lawrie explains, “occurring in the gaps between other art movements and practices. It derives from two distinct traditions: fieldwork and experimental music.”

These two tendencies can be felt across Site & Sound, pulling and mixing in different directions. Rachel Meyers’s Southern Ecophony: Wind and Water (2020), for instance, playing outside the gallery entrance, sits more obviously in an experimental music tradition, with its original composition for two violins blended with recorded sounds from the Tasmanian coast. Likewise, Philip Brophy’s Atmosis (2013), which takes city sounds (Tokyo and rooftop Melbourne) and transcribes them for musical instruments.

Paul Carter and Christopher Williams’s Cooee Song (1990/2019) blurs lines between scriptwriting for theatre, spoken-word performance (veering fleetingly towards something like Laurie Anderson’s experimentation) and sound capture to reimagine early colonisation and cross-cultural encounter. Daniel Browning’s Latitudes: A Song Cycle (2015), which he describes as an act of decolonisation, an effort at “unmapping the end of the world”, is almost ethnographic in approach, dwelling (in part) on the human voice as his artist-collaborators respond to three very different acoustic sites of Lake Mungo (an almost “soundless basin depression”), the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage route in Japan and the Valcamonica alpine valley in Italy.[11]

Other pieces recall a more natural science approach of data gathering, a field that has recently bloomed through “bioacoustics”, with huge data sets collected through small acoustic recorders positioned near endangered or difficult-to-access species. [12] Some of these projects, which listen to nature, are attractive as citizen science initiatives that invite amateurs (such as this writer) into the field. [13]

**

I visited Site & Sound twice, first for outdoor installations that launched in December 2020 when the McClelland reopened after COVID-19 disruptions. A larger cohort of gallery installations opened in late January 2021, followed by a rollout of ongoing events in collaboration with RMIT’s Spatial Information Architecture Laboratory (SIAL), including a major event with Liquid Architecture.

To find the outdoor installations, visitors follow a simple map of the sculpture park. Clustered across three sites, these pieces don’t have any signage and, unless you know the park well, they are not necessarily easy to locate. Lacking visual cues, I found myself wandering the grounds with a heightened anticipatory listening, unsure whether any given sound (birdcall, distant traffic, wind stirring foliage) might signal the beginning of a piece. Once encountered, though, the works are unmistakable.

When I reached a dry creek bed, Prasetyo’s City Noise – Sound (Art) and Disaster (2006) was playing. From among a dense stand of shrubs and trees came a scramble of hectic urban sound, distant and almost stylised human screams, thunder and rain, and a Muslim call to prayer. This “composed memory” is dedicated to friends and relatives who suffered tsunami and earthquake disasters in Indonesia, and it creates a great sense of disjunction between the site of installation (a windless thicket of Langwarrin bushland on a hot summer morning) and an unelaborated and urgent narrative of some kind unspooling. [14]

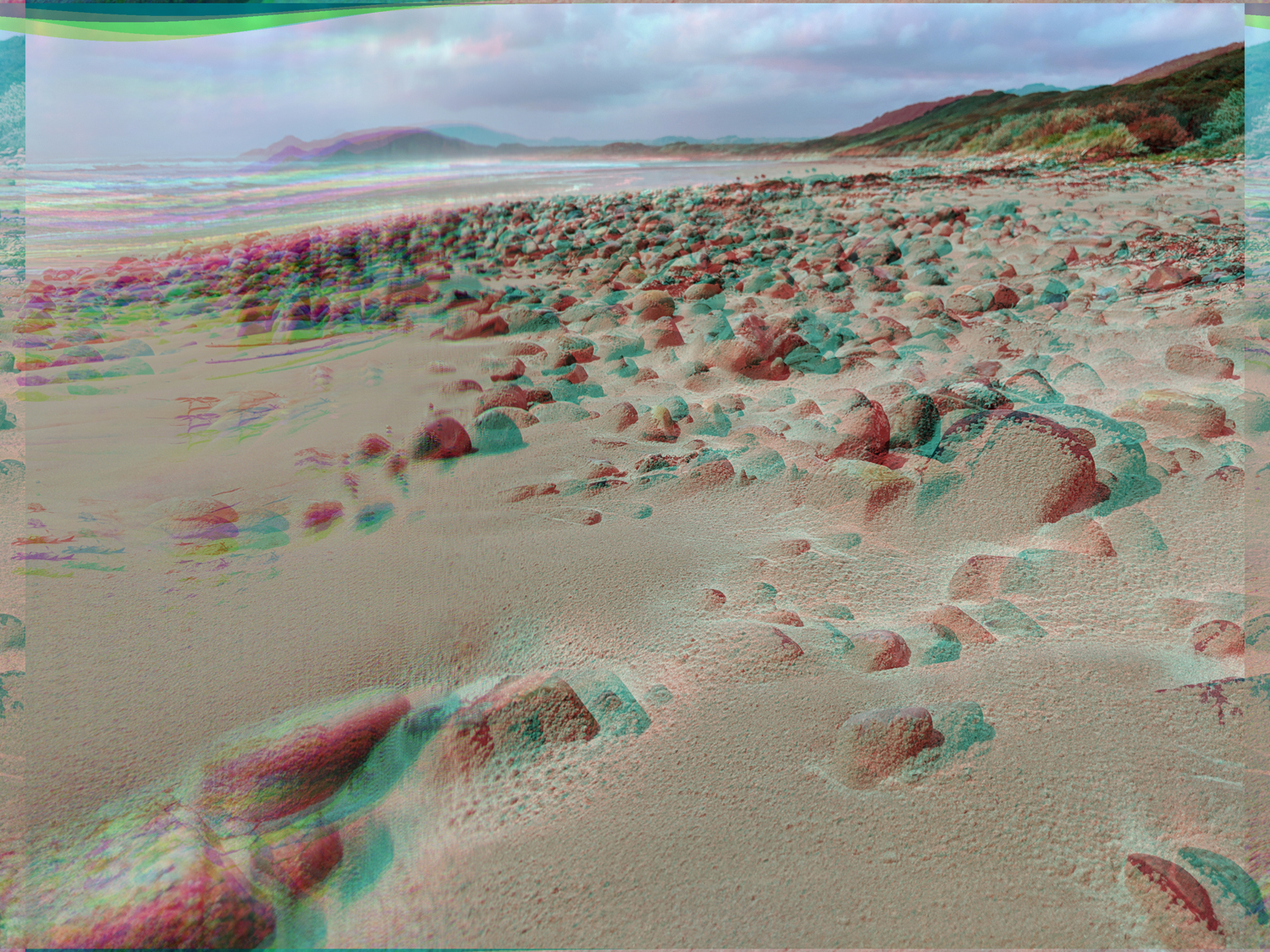

The sense of one environment transposed and co-locating with another is only heightened with Reuben Derrick’s Poranui (2012), recorded on a stretch of wild coastline on New Zealand’s South Island. From this eight-channel installation, the sound of ocean meeting rock swirls amid the vegetation, emphasising the motion-filled spatialised quality of sound, which is, after all, a “wave of pressure caused by vibration passing through air”. [15] Shifting from speaker to speaker, Derrick’s waves seem to heave overhead among foliage, surging and circling about the listener. There is an uncanny sense of water flooding the dry landscape, conjuring a deep past when land may have been seafloor, or a future where sea levels rise once more.

In a further curatorial gesture towards drainage patterns in the McClelland landscape, Leah Barclay’s Hydrology (2016) channels underwater animals groaning, moaning and clicking, the gloop of water sucking beneath hull of boat or some other object, an unidentified swooping noise. Working in coastal mangroves in Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve in Mexico, Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef and frozen rivers in Norway, Barclay uses hydrophones as a “non-invasive way of understanding changing aquatic ecosystems” and Hydrology functions as a kind of collaged report back to the terrestrial world.[16]

**

On my second visit, I entered the main Murdoch Gallery space to find Philip Samartzis and Eugene Ughetti’s Polar Force (2018/2020) playing. The room is designed (with the assistance of RMIT Master of Design, Innovation and Technology students and Associate Professor Ross McLeod) like a swimming pool: with a shallow end of listening at one end, and the deepest section in the middle of the room where the largest concentration of sound converges from 24 speakers. Listening is thus shifted away from the atomised experience so common of gallery headsets into a shared, visceral experience.

When encountered at the “deep end” of the pool, Polar Force is a bodily as much as an aural experience, with sound travelling not just through ears but feet, bones and flesh. The scale conjured by this piece is immense, alluding to some kind of pulse at a planetary level. I was reminded of Open Spatial Workshop’s video of sand dunes at Wilsons Promontory, shown at Converging in Time (MUMA, 2017). Individual grains of sand shift, settle, resettle, slide and flick, hinting at imponderable timescales. Just as the patient work of a migrating sand dune might outlive the human species, the powerful twisting, straining metallic groan of wind and ice hints at a nature “forever beyond the tampering reach of man”, as scientist and nature writer Rachel Carson wrote (uncertainly) in 1958.[17] Simultaneously, Polar Force serves as a portent of the environmental disaster in which we are all implicated. A strength of the work is that both things seem possible at once.

In the same gallery, among numerous other works, Jana Winderen’s Spring Bloom in the Marginal Ice Zone (2017) reveals underwater sounds of the “dynamic border between open sea and sea ice”[18] in the Barents Sea near the North Pole – bloom of plankton, bearded seals and migrating humpbacks, orcas and spawning cod. These thread together in a braid of haunting whistles, trickling, crackling and low, plaintive mammalian calls sounding at intervals. It is a mysterious, inaccessible world brought to the surface through audio topography and is mesmeric in its effect.

The deep sea has long been a “final frontier” of exploration, lingering well beyond the efflorescence of 18th- and 19th-century expeditionary cultures linked so closely with colonisation. While I was writing this essay, for instance, researchers accidentally discovered marine organisms on a boulder on the sea floor beneath 900 metres of Antarctic ice shelf where no life was thought to exist. [19] Winderen’s piece gives voice to such little-understood recesses. The “sounds of living creatures become voices in the current political debate concerning the official definition of the location of the ice edge”, she suggests. [20] In this politicisation, they are not so different to the extinct huia’s call.

**

Perhaps unsurprisingly, because of their acoustic affordances, certain leitmotifs circulate, bleed and morph across the works taken as a whole – water in its many guises (flowing, dripping, trickling, sucking, surging); birdsong; insects (exemplified in Chris Watson’s Namib, 2013, with insects singing into the night in Africa’s Namib Desert); underwater lifeforms that use sound to communicate; weather phenomena (both wild and understated, as in Christophe Charles’s Sounds of Weather); the idea of making what is usually invisible or inaccessible “sense-able”; and, to a lesser extent, urban sound (a child’s passing exclamation, a moment of collision, a bottle rolling in Nigel Frayne’s What U Might Have Heard, 2016).

None of the pieces in Site & Sound are interactive. They are not triggered inadvertently by audience movement, for instance, or by more deliberate participatory acts, such as those elicited in the Material Sound exhibition at Manning Regional Gallery. [21] However, the outdoor setting, in particular, results in a form of “collaboration” between soundscapes of the hosting site and those of the works. Sounds from the surrounding landscape flow into, disrupt, interject and create segue-ways among recorded sounds.

When a sequence of outdoor works comes to completion, it is followed, in a playful nod to John Cage’s 4’33”, by a brief period of silence. This is a risky curatorial strategy in that audiences may miss the works entirely. On the other hand, it creates the kind of active listening and interrogation of “silence” that Cage’s piece is renowned for. In the interval between pieces, surrounding sound takes on new immediacy and significance – the cascading notes of a butcherbird, wattlebirds squabbling at a nectar source, a slight stirring of wind, the doppler effect of a passing car, an insect pulsing in summer sun. A liminal space is created between what may or may not be a piece of sound art and the perpetual suite of varied sounds in everyday surroundings that so often become almost inaudible due to familiarity.

In a moving account of his creation of Latitudes, Browning says:

"All I wanted was to capture the essence of each place acoustically. We all know how hard that is. No field-recordist will say it’s an easy thing to do and it seems simple but it’s such a big task … I tried very hard. I was obsessed with the sound of each place.[22]"

One of the great achievements of Site & Sound is its conveyance of this passionate obsession with an acoustics of place. Another is the educative role the exhibition plays in bringing this niche genre before wider audiences (assisted by an informative and engaging catalogue with contributions from key figures in the field). Still another is its emphatic and unapologetic stripping away of the visual that gallery goers are more familiar with, to facilitate a heightened listening that demands patience – not just to the pieces themselves but to the rapidly changing ecological world around us.

Footnotes

- ^ Julianne Lutz Warren and Matthew Young, Extinct Birdsong — Huia Echoes, The Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, USA, 2012.

- ^ Daniel Browning, ‘I hear everything: the cultural context of listening’, Site & Sound: Sonic art as ecological practice, McClelland Sculpture Park + Gallery, 2021, pp. 12–13

- ^ Frans Ari Prasetyo, ‘“City Noise”: Sound (Art) and Disaster’, Journal of Sonic Studies, 14, 2017: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/369776/369777

- ^ 'Barry Truax, Ocean Deep’, Site & Sound, p. 84.

- ^ ‘Ros Bandt, Raptor’, Site & Sound, p. 49.

- ^ A. Frances Johnson, ‘Trent Parke: WWI Avenue of Honour’, ABR Arts, 8 February 2021: https://www.australianbookreview.com.au/arts-update/101-arts-update/7407-trent-parke-ww1-avenue-of-honour-art-gallery-of-ballarat; Paul Gough, ‘“Planting Memory”: the Challenge of Remembering the Past on the Somme, Gallipoli and Melbourne’, The Gardens Trust, vol 42, 2014, pp. 3–17.

- ^ Pep Canadell, Chief Research Scientist, CSIRO Climate Science Centre, personal communication, February 2021; Dana Bergstrom, Euan Ritchie, Lesley Hughes and Michael Depledge, ‘“Existential threat to our survival”: see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing’, The Conversation, 26 February 2021: https://theconversation.com/existential-threat-to-our-survival-see-the-19-australian-ecosystems-already-collapsing-154077

- ^ Pep Canadell and Rob Jackson, ‘Earth may temporarily pass dangerous 1.5°C warming limit by 2024’, The Conversation, 9 September 2020: https://theconversation.com/earth-may-temporarily-pass-dangerous-1-5-warming-limit-by-2024-major-new-report-says-145450

- ^ Andrew Whitehouse, ‘Listening to Birds in the Anthropocene: The Anxious Semiotics of Sound in a Human-Dominated World’, Environmental Humanities, 6, 2015, pp. 53–71; Saskia Beudel, ‘Listening to Birds in a Changing World’, Living with the Anthropocene: Love, Loss and Hope in the Face of Environmental Crisis, Cameron Muir, Kirsten Wehner and Jenny Newell (eds), Sydney: NewSouth, 2020, pp. 110–127.

- ^ Danielle Celermajer, Summertime: Reflections on a vanishing future, North Sydney: Hamish Hamilton, 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Daniel Browning, ‘Latitudes: A Song Cycle’, Soundproof, Radio National, 25 September 2015: https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/soundproof/latitudes-a-song-cycle/6794916

- ^ Anders Gyllenhaal, ‘With bioacoustics, conservationists try to save birds through their songs’, Washington Post, 12 January 2020: https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/with-bioacoustics-conservationists-try-to-save-birds-through-their-songs/2020/01/10/8b800048-0c9a-11ea-bd9d-c628fd48b3a0_story.html

- ^ Saskia Beudel, ‘Friday Essay: Frogwatching – charting climate change’s impact in the here and now’, The Conversation, 6 July 2018: https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-frogwatching-charting-climate-changes-impact-in-the-here-and-now-98161

- ^ ‘Frans Ari Prasetyo, City Noise – Sound (Art) and Disaster’, Site & Sound, p. 76.

- ^ ‘Steve Stellos Adam, Passing By … More Quickly’, Site & Sound, p. 48.

- ^ ‘Leah Barclay, Hydrology’, Site & Sound, p. 50.

- ^ Rachel Carson, letter quoted in Linda Lear, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, Boston: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009, p. 310.

- ^ ‘Jana Winderen, Spring Bloom in the Marginal Ice Zone’, Site & Sound, p. 86.

- ^ The discovery “has led scientists to rethink the limits of life on Earth”. Ian Sample, ‘Researchers rethink life in a cold climate after Antarctic find’, The Guardian, 15 February 2021: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/feb/15/researchers-rethink-life-in-a-cold-climate-after-antarctic-find

- ^ ‘Jana Winderen, Spring Bloom in the Marginal Ice Zone’, Site & Sound, p. 86.

- ^ Ann Finegan, ‘Material Sound’, Artlink, 5 November 2020: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4868/material-sound/

- ^ Browning, ‘Latitudes’, Radio National.