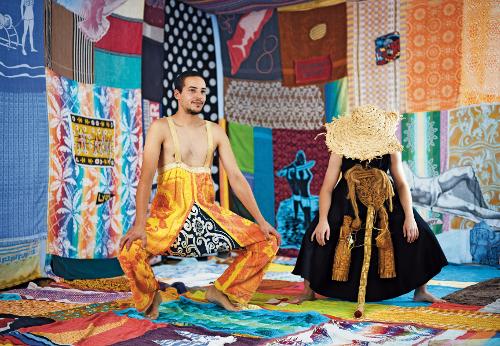

Melanie Jame Wolf’s Pop-Cultural Drag: The Chronopolitics of Labour, Libido and Image

Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982) portrayed an unfunny would-be comic Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro) kidnapping his comic hero (Jerry Lewis) as a frenzied effort to nab the spotlight at whatever cost. Too clever for its own good, The King of Comedy succeeded as a critique of the rampant and delusional desire for fame and overnight celebrity within a late 20th-century televisual milieu. But commercially it was a failure, dubbed “box office poison” and chalked up to not being funny at all. The price of Rupert Pupkin’s comic quest warns of a blurring of fantasy and reality that results from an overinvestment in media imagery. One telling scene shows the wannabe stand-up performing in his basement to a cardboard audience, the camera panning back to reveal a cold and empty sound stage where canned laughter spurs him on, even if it’s only heard as diegetic sound in his imagination. “Rupert can be understood as an existential clown,” writes film critic Christina Marie Newland, “a comedian who is his own perpetual joke”.