The Great East Japan Earthquake and the subsequent disasters of 2011 provided a keenly felt existential matrix to the 2014 Yokohama Triennial. Yasumasa Morimura's title for the show, ART Fahrenheit 451: Sailing into the sea of oblivion combines Zen poetics with the recognition of dangerous reality. As the title indicates, another matrix was Ray Bradbury’s 1953 future fiction Fahrenheit 451, a novel depicting a world where all books are burnt so that whatever knowledge remains is compromised and suspect while machines and technologies reinforce a dull conformity of minutely monitored social isolation. Bradbury was surprisingly prescient, yet while the Rule of Law, censorship and surveillance were leitmotifs, this exhibition was not a bleak politically correct sermon.

Yasumasa Morimura is an artist much admired for the consistent strength of his interrogation of the nature of power relations, in particular the hegemony of the male gaze with an extraordinary series of photographic (self) portraits. So I was intrigued to discover that he was the Artistic Director/Curator of the 2014 Yokohama Triennial. Even though the artist has had 40 years curating his own work, my umbrella anxiety for Morimura was that the logistics /aesthetics of coherent display in these mega shows, the management of a large number of disparate works across multi venues is a difficult task even for an experienced museum curator (über or not), a fact unfortunately evident in recent manifestations of the Biennale of Sydney.

My anxieties were quickly allayed, encountering the work of 62 artists: there was wit, play and subversion aplenty but also a quiet resolve and a belief in the supernatural powers of art, something that, in Morimura’s words, 'enables us to respond to every forgotten thing that is neglected, carelessly overlooked or simply out of our sight’.

Most striking was the simple relevance and direct mode of address to the audience through juxtapositions that made complex relational conceptual works, ‘difficult’ and ‘alienating’ in any other context, accessible sensuous teasers redolent with humanity. Heralding further delightful provocation, English artist Michael Landy made a see-through architectonic scale dumpster where the general public were invited to throw away their old, now unloved, art. Landy proclaimed his Art Bin (2010/2014) as ‘a monument to creative failure’.

Another iteration of the anti monument, Turn Coat/Turn Court: constitution-constellation (2014) by Temporary Foundation was a literal tour de force that overlooked the Landy piece. It was comprised of a set of toy-like, luridly coloured and pristine environments - a court of law, a tennis court and prison cells – in startlingly clear references to systems that attempt to manage bodies.

At the opposite end of the grand entrance hall, The Drifting Classroom (2014) of Kama Gei was a riot of colour and participatory interaction after somewhat dour meditations on the isolating purity of abstraction with works by Agnes Martin, Kasimir Malevich, and John Cage. Marcel Broodthaers’ hilarious sound work Interview with Cat (1970) and Isa Genzken’s cement transistor radio World Receiver (1982) complete with two antennae reiterated but also challenged the Duchampian trope of the ultimate impossibility of true communication. Maybe there is another way.

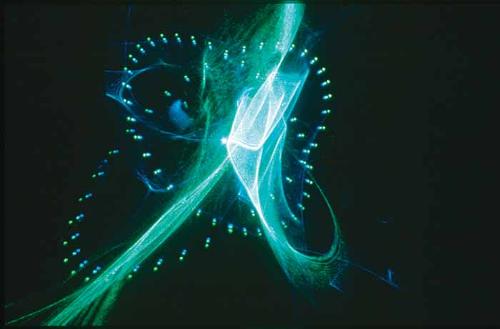

Sensate recognition of elements of life in the minor key became points of wonderment: such as the depiction of a stained mattress, string and cardboard boxes in the paintings of Zhang Enli. The low abject materials of the 1970s chewing gum Photosculptures (1972) of Alina Szapocznikow and Andy Warhol’s Come Paintings (1970s) made the vanitas and performative underpinnings of Pop transcendent while the subtle tics, shakes and occasional rumblings of the intergenerational collaborative sound installation Chamber of a musical composer (2014) by Yuko Mohri and Victor C. Searle was both amusing and captivating.

There were a number of works with quasi-documentary anthropological methodology or content. Taryn Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII (2008–11) used photographs, personal letters, official statistics and other documentation to hurtle the viewer into a contemplation of what can constitute knowledge and how information is collected, used and interpreted, while Eric Baudelaire’s video The Ugly One (2013) a strangely romantic and cathartic narrative set in Beirut used the juxtaposition of French, Arabic, Japanese and English languages to reiterate a sense that we are all Orpheus-like figures stumbling through life slowly coming to knowledge. Indeed the idea of myth-making and primordial spirituality as a sort of solution to present societal ills infused much of the exhibition. Just the act of making can be a balm – witness the quiet narrative fetishism of Joseph Cornell, Pierre Molinier and Chiyuki Sakagami as exemplars. Or the giant guardian figure by Masunobu Yoshimura Oh-Garasu (Japanese homonym of The Large Glass and a big crow (1970).

I was taken aback by my journey through the exhibition. It was at once gut-wrenching and inspiring.