Search

You searched for contributors, issues and articles tagged with Environment ...

Contributors

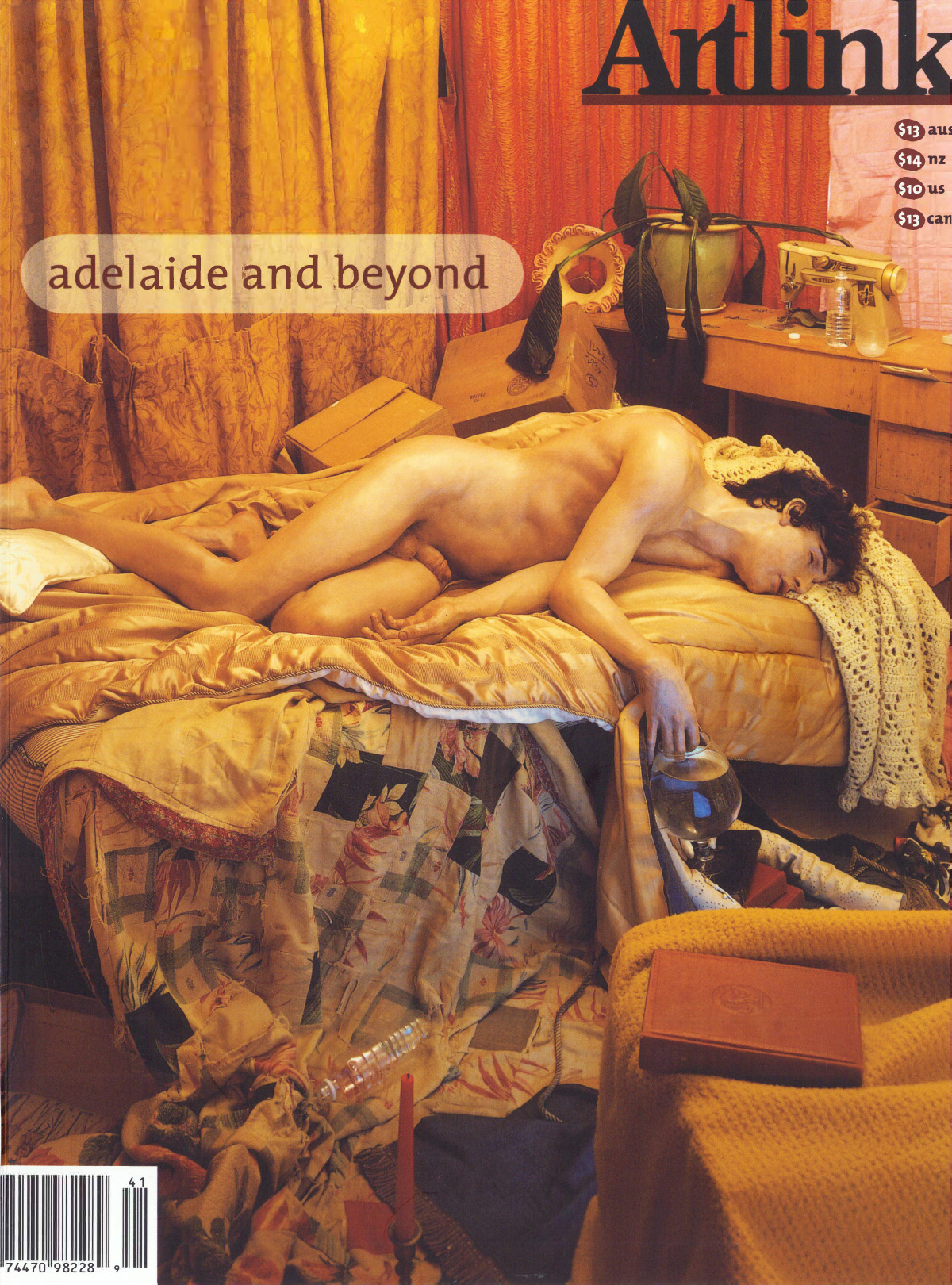

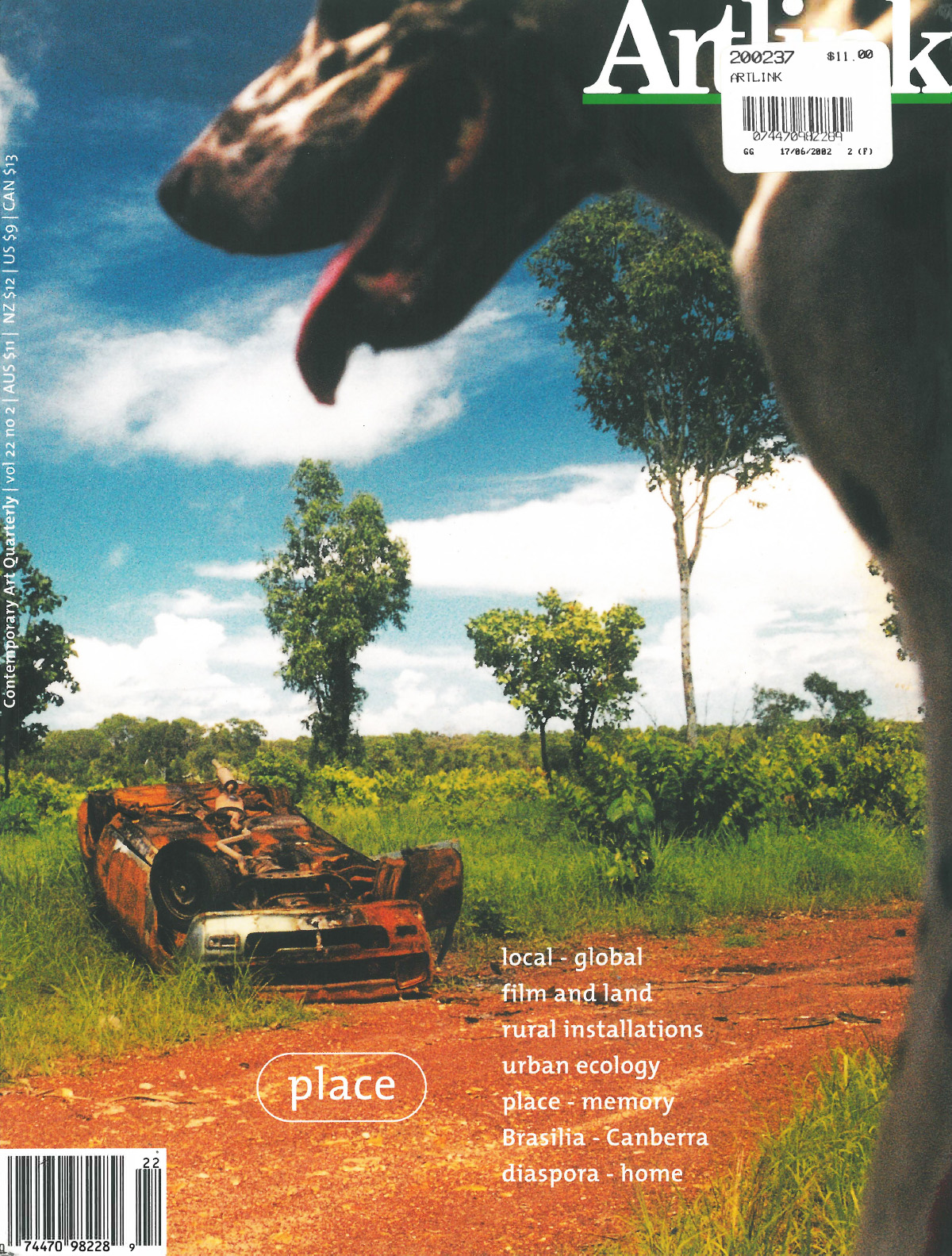

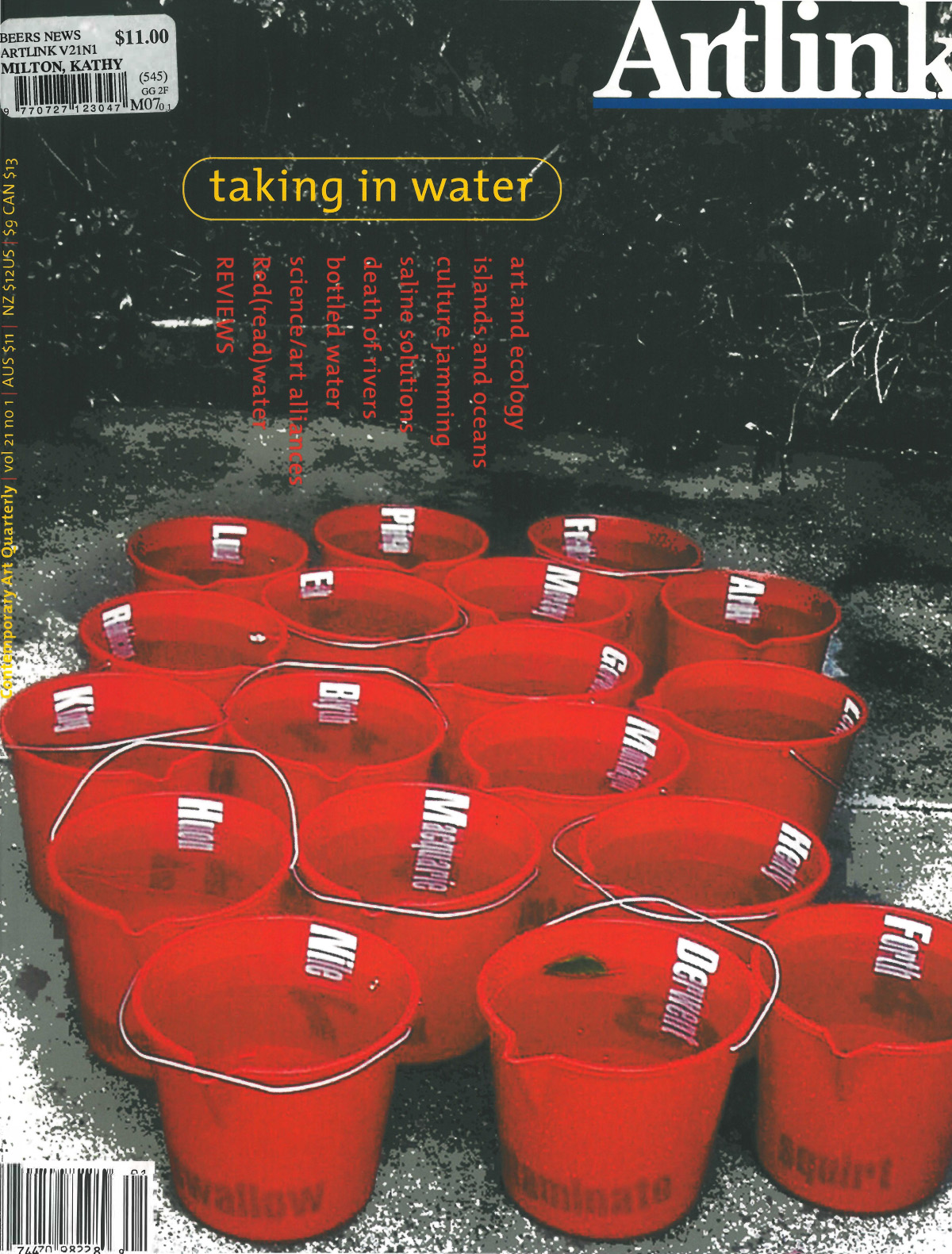

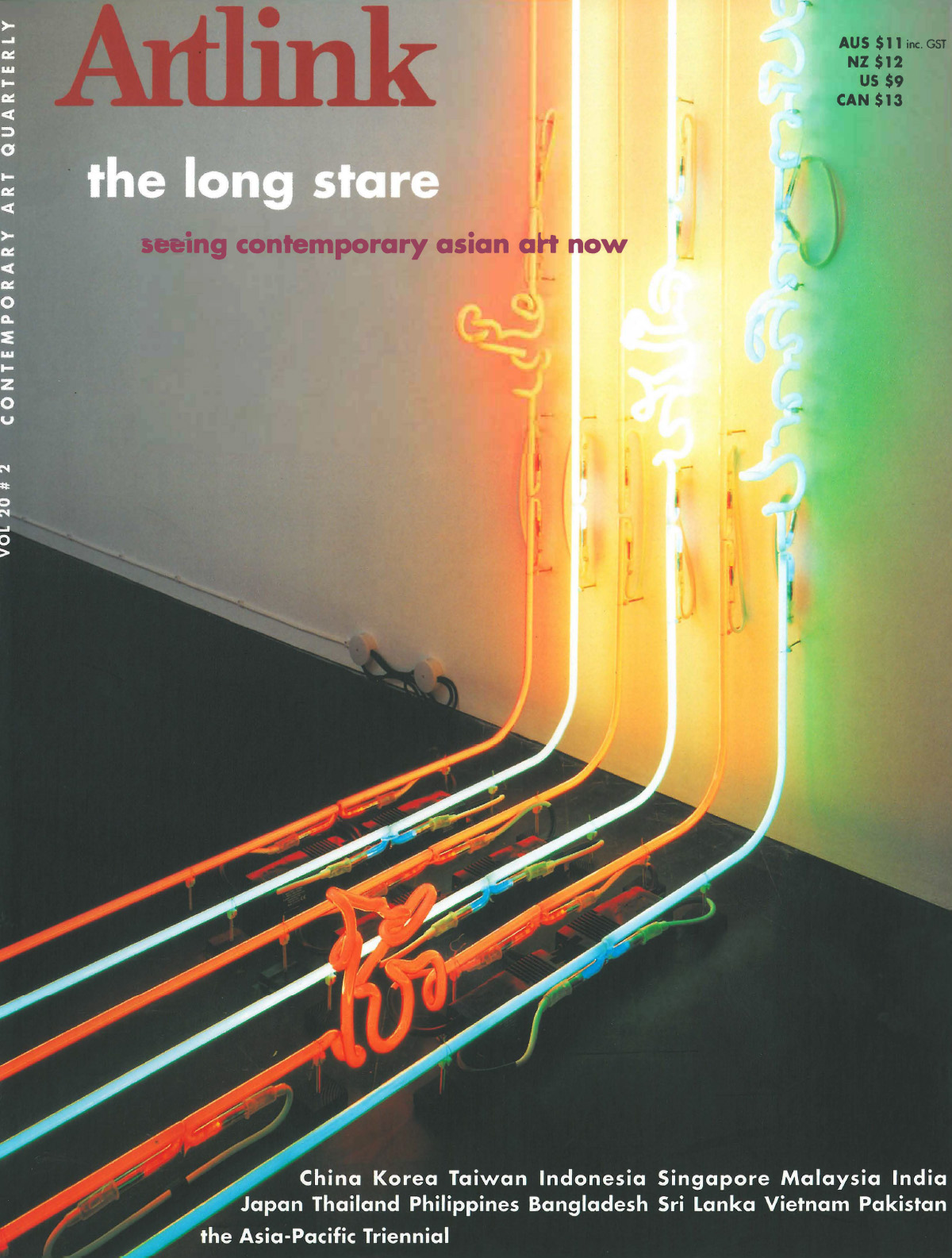

Issues

Articles

I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china.

Oscar Wilde, 1874

As an aesthete Wilde surrounded himself with beautiful objects. This epigram from his Oxford days paid tribute to and satirised the Victorian craze for the exotic. At Oxford University Wilde was introduced to the culture of aesthetes by art critic and philanthropist John Ruskin whose writings on craft also influenced William Morris.

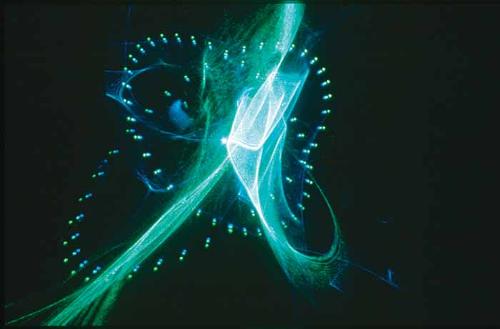

Wardlipari is the homeriver in the Milky Way.

Purlirna kardlarna ngadluku miyurnaku yaintya tikkiarna.

The stars are the fires of people living there. Yurarlu yurakauwi trruku-ana padninthi Wardlipari.

Yurakauwi the rainbow serpent goes into the dark spots in the Milky Way.

Ngaiyirda karralika kawingka tikainga yara kumarninthi.

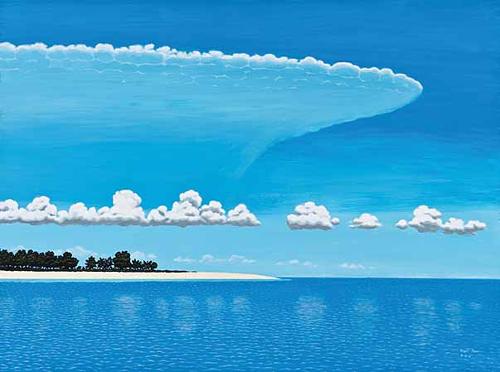

When the outer world and the sky connect with the water the two become one.

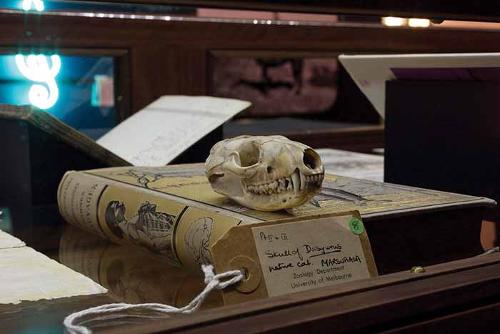

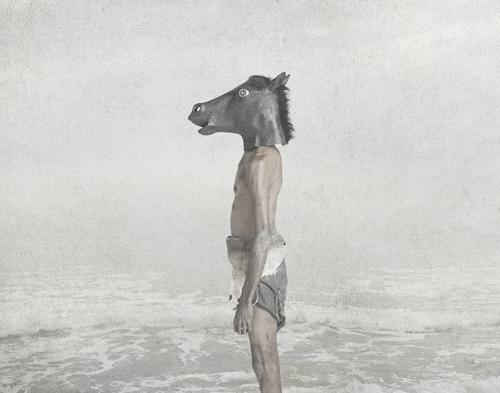

Sometimes the truth is impossible to hear. At year’s end, dinner table conversation turns from climate change to mass extinctions, and people consult their pocket encyclopaedias for facts. Someone asks: “Exactly how many birds in Aotearoa have gone extinct?” Even Wikipedia claims an incomplete list. In Te Ara ecologist Richard Holdaway tells the numbers more clearly: 50% of vertebrate fauna gone in the 750 years since human arrival in New Zealand. Numbers overwhelm in Australia too. Here, humans have been living amidst other animal species for tens of thousands rather than hundreds of years, and the list of extinctions add to our dinner table litany.

Four humanimals creep, crawl, sniff and moan their way through a seated audience, towards an empty performance area which awaits their presence. Snorting and snuffling is audible as the liminal creatures rub themselves against giggling audience members, rolling across laps and crawling under chairs. Their faces are painted with dark bands across the eyes—like a species of bird, bandit, or warrior. When they reach the performance area, they crouch in a circle, continuing their muffled cries as one of them stands.

From the early 1970s, driven by drought and degradation of interior wetlands, the Australian White Ibis (Threskiornis moluccus) began migrating to the nation’s coastal cities, towns and inland centres from north Queensland through to Perth. Ibis have flourished in urban spaces, where there is a ready food supply guaranteed by our endemic over‑consumption. Their robust colonisation and presence has garnered the bird a reputation as unwelcome pests and interlopers, reflected in the quotidian idiom: dumpster diver, flying rat, tip turkey, pest of the sky, trash vulture, dump chook, bin chicken, bin chook.

“I don’t know” sings the chorus in response as Madison Bycroft rallies off quip after quip the characteristics of a mollusc life-world while occupying a mollusc-like dress at the back of the mollusc-like stage. What this lecture-performance Soft Bodies (2017) addresses is a problem that faces much of the arts and humanities in the twenty-first century: a grappling with the ontological becomings and tentacular thinking, of those things that are and are not us. As science continues to illuminate the molecules and viruses that make up our bodies, we are plunged into a world where ideas about what distinguishes us as humans (and our understanding of what a human is) have become increasingly vague. As environmental philosopher Timothy Morton avows in solidarity, we are more non‑human than we are human. So what happens when boundaries that previously demarcated one thing from another disintegrate? And what do molluscs have to do with it?

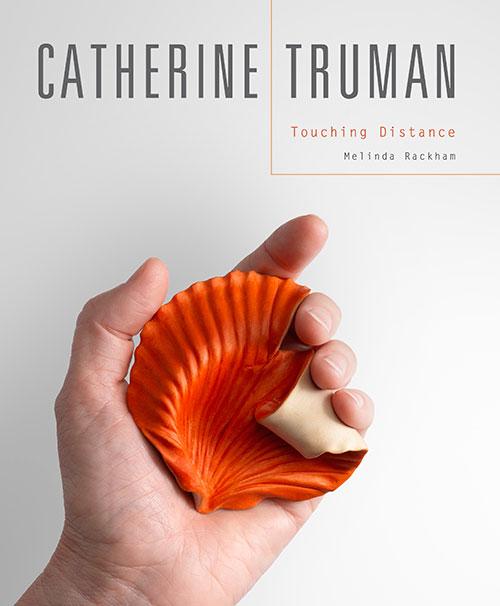

Theories are living and breathing reconfigurings of the world.

Karen Barad, from “On Touching—The Inhuman that Therefore I am.”

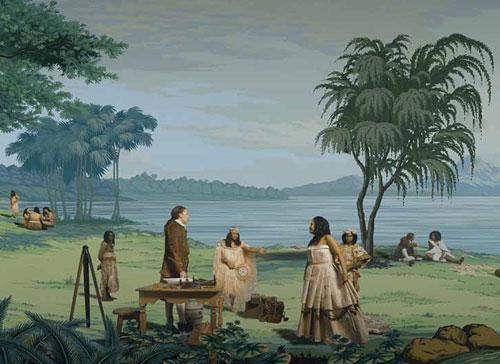

Contemporary animal theory confronts some of the most profound issues of our time—what it means to be human in the Anthropocene, anthropocentrism and the mass extinction of species, the rights of nonhuman animals and the future of ethical thinking. Artists, writers and filmmakers explore these and related issues in works that are experimental and challenging, testifying to this time of crisis. These include Michael Cook’s human–nature studies (Civilised, 2012; Invasion, 2017), Janet Laurence’s work on extinction (After Eden, 2012), Patricia Piccinini’s exploration of the posthuman (Evolution, 2009), Sue Coe’s bearing witness to slaughterhouses (Dead Meat, 1996; Porkopolis, 2001), J.M. Coetzee’s writings on animals and ethics (Elizabeth Costello, 2003, Disgrace, 1999) and Nicolas Philibert’s indictment of zoos in his documentary, (Nénette, 2010).

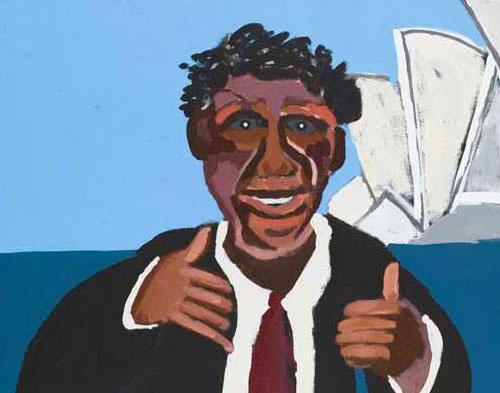

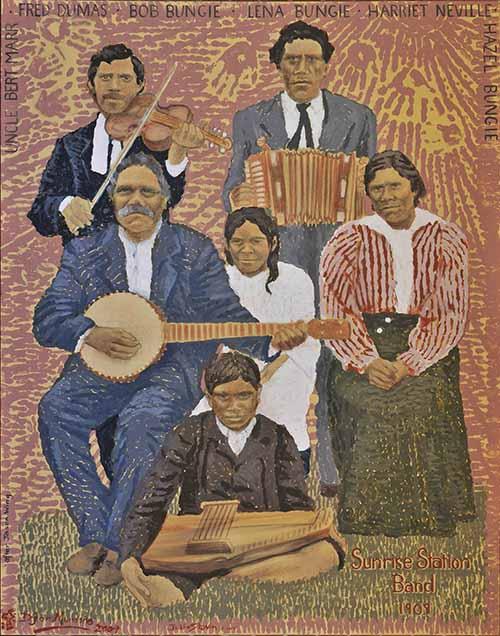

Vivid and arresting paintings of Australian wildlife are the hallmark of an artist known mononymously as Turbo. Born Trevor Brown (1967–2017) in Mildura, he took up painting in his mid‑thirties after he had relocated to Melbourne. He rapidly gained critical and commercial attention for works using a quick and direct application of pure colour, bursting with raw energy, and featuring a varied cast of native fauna. So exclusive—obsessive, even—was his portrayal of animals that there arose a kind of origin story explaining his single‑mindedness: “Uncle Herb [P]atten, the man he loves as a father, once asked Brown why he only painted animals. He replied that when he was fifteen and living on the Mildura streets and the Murray River bank, the animals were his only friends.” Other explanations Turbo gave for his choice of subject matter included, “Animals are my friends. They come to me in my dreams” and “When I paint, I feel like I’m in the Dreamtime and can see all the animals that live there.”

In 2016 the arts in Australia inhabit a dystopian world. It could be described as a place of absurdist contradictions, where only those who have mastered the arcane rules of the Hunger Games have any chance of surviving. Possibly the greatest change is that arts funding is now a partisan political issue in a way that it has not been for some generations. In the past there were concerns about the internal politics of art bureaucracies, but now the allocation of funds to support the arts (or not) has become a party‑political issue. The Commonwealth Government recently presided over the greatest reduction in arts funding in Australian history, but when questioned on this in a public forum, the art‑loving/art-collecting Prime Minister was unaware of the impact of his party’s budgets on the arts. It is probably unfair to blame the current Prime Minister for the devastation that was wrought in the time of his predecessor.

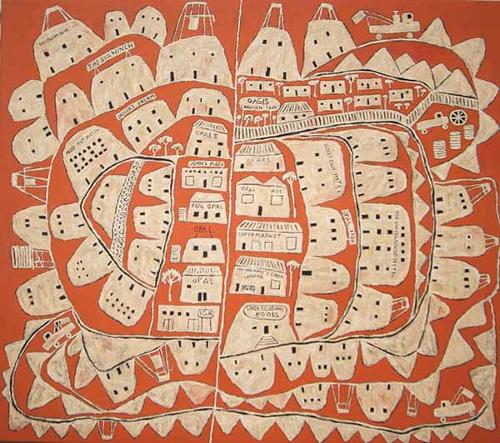

Nearly two decades ago, when artist Rodney Glick and I started discussing the possibility of developing an international contemporary art space in a small country town, people found the idea both comical and intriguing. They laughed when they heard it first but then reconsidered, perceiving a potential beyond the apparent joke. The reason for such hilarity is obvious: contemporary art is so closely associated with the inner city areas that the idea of transplanting it among paddocks and feedlots came across as funny, like a hairy man wearing a tutu.

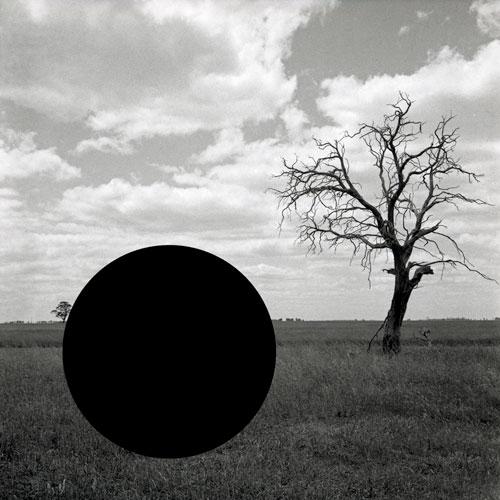

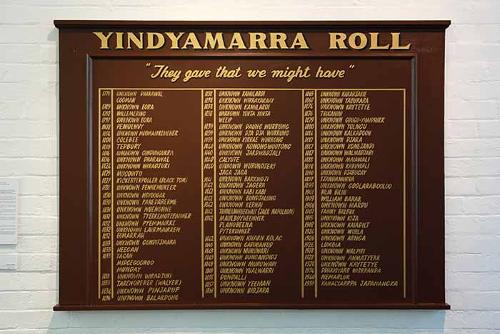

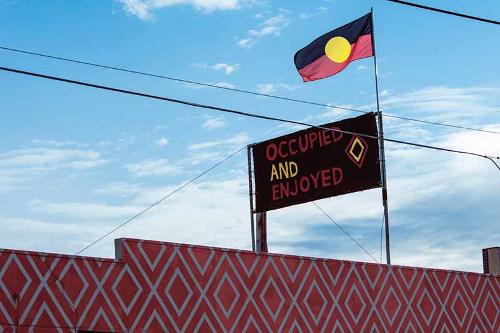

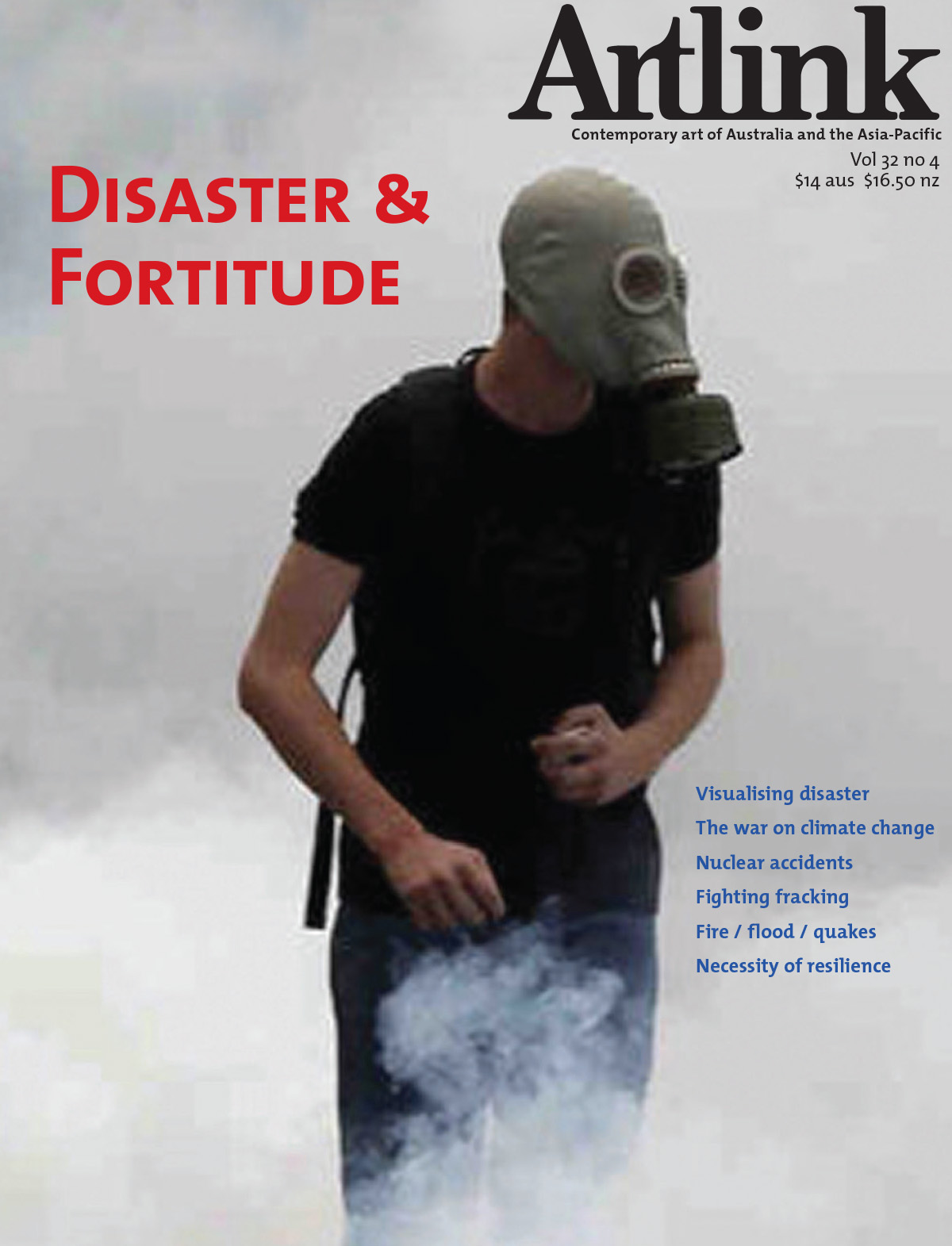

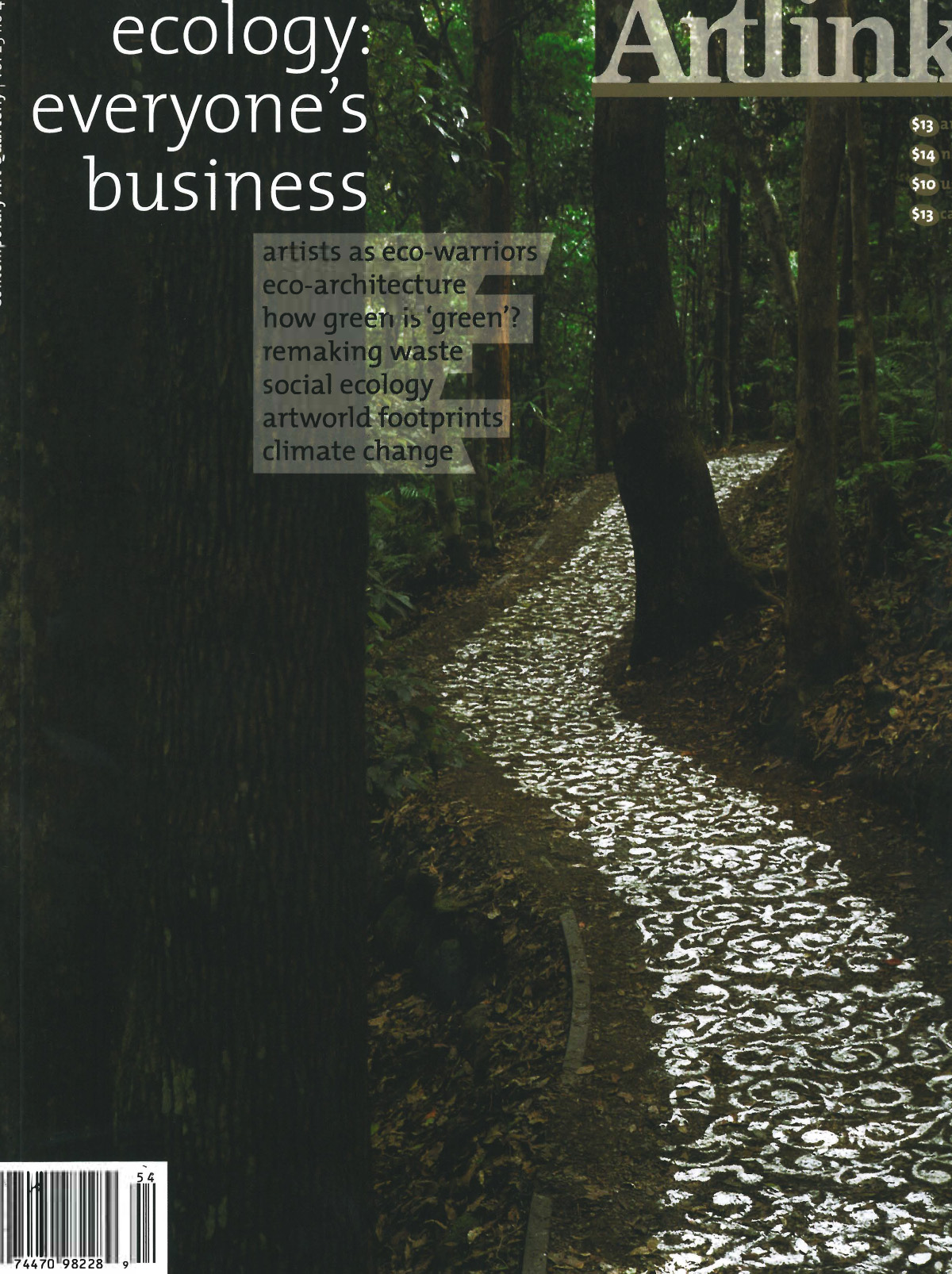

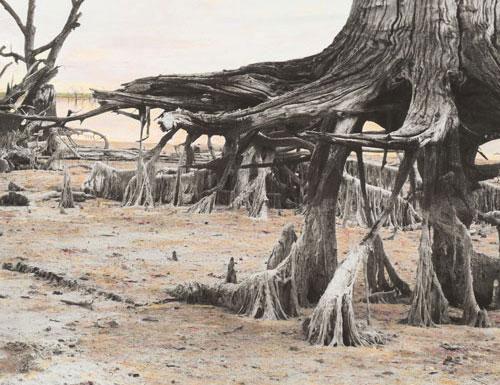

Solastalgia has come to signify distress caused by environmental damage. The term, originally coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht, specifically addressed the condition of existential distress caused by the physical destruction of one’s immediate environment. As the global extraction industries and the financial institutions that bankroll their reach increasingly dominate, with direct impacts on land, solastalgia is fast becoming a common contemporary condition associated with the loss of ground in our occupation of the planet and a general sense of helplessness.

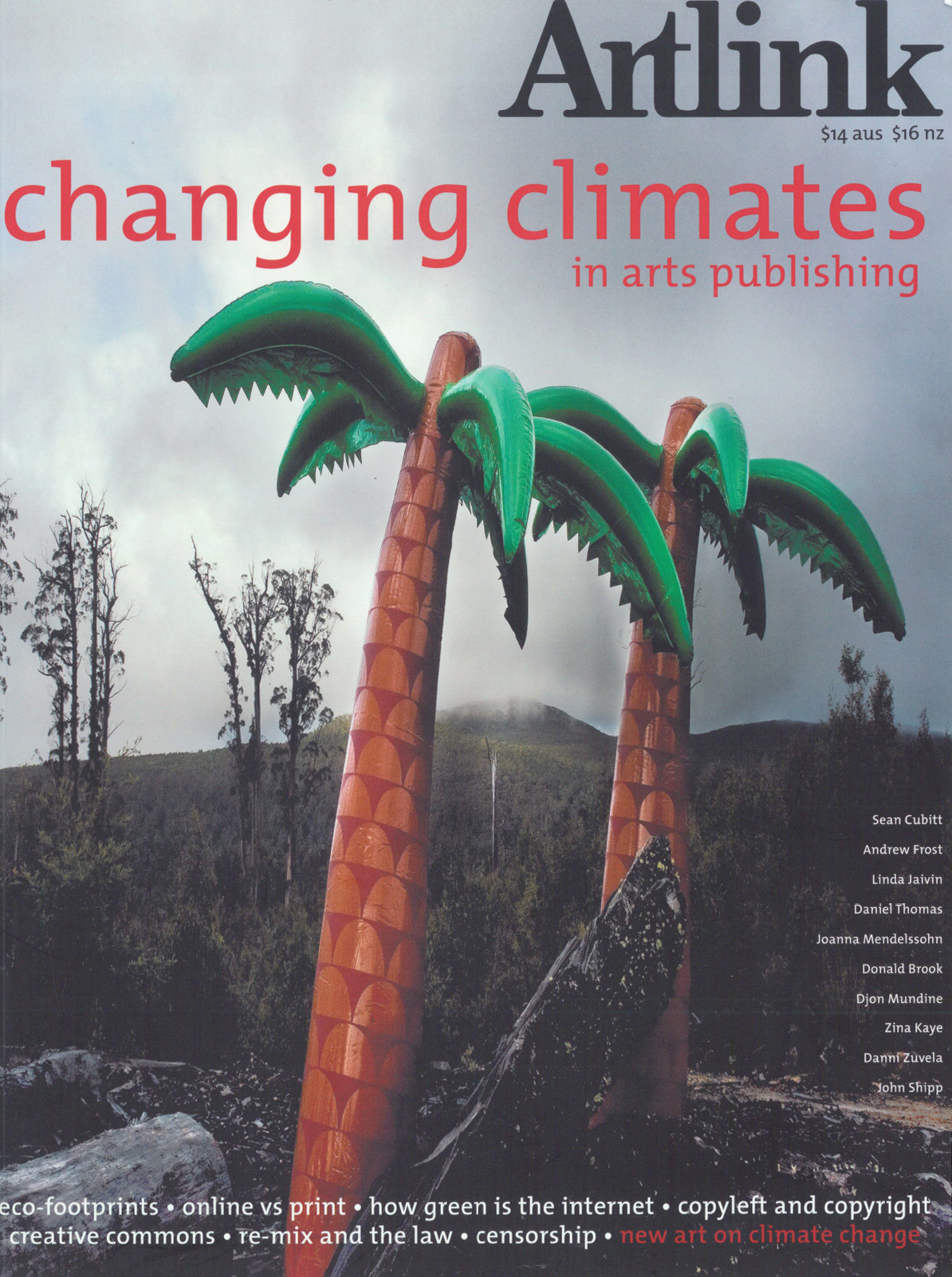

The Palmer Sculpture Biennial is a characteristically transient, remote art event that takes place in the Mount Lofty Ranges of South Australia, some 70 kilometres east of Adelaide. Led by sculptor Greg Johns, who purchased the 163‑hectare property of rain‑shadow country at Palmer in 2001, it has become a place for artistic nomads, who converge on the landscape to create ephemeral and site‑specific art. This unique art event that takes place every two years is aligned with an ongoing program of land regeneration, supported by a community of artists and environmentalists.