14 Queensland Nations (Nations imagined by RH Matthews) created by Kamilaroi artist Archie Moore was originally developed as an installation for the symposium Courting Blakness at the University of Queensland in 2014 with the intention to disrupt the courtyard space. His flags became a powerful symbol of an anthropologically-imagined nationhood. When transporting this exhibition to Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute it became something more; it transformed from sign and signifier into the Barthesian concept of mythology to speak back to dominant culture. Freed from the restrictions of flag protocol and storied for visiting gallery groups it evolved into another narrative.

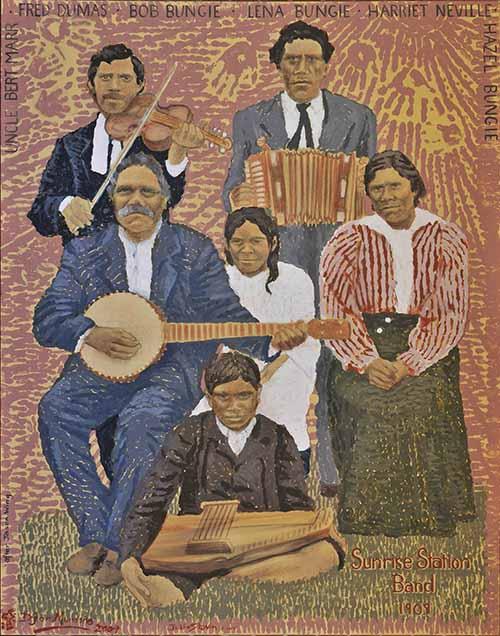

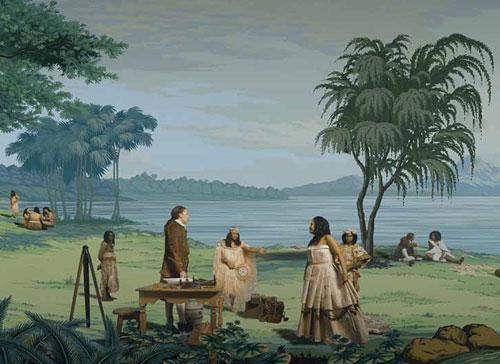

Moore based his flags on the work of self-taught non-Indigenous early 19th century anthropologist RH Matthews who, within his own white privilege and position of knowledge, mapped the boundaries of Indigenous nations within New South Wales and Queensland. Just as the inventor of the Aboriginal flag, Harold Thomas, imagined a flag to unite Aboriginal Australians using recognised symbology, so Archie Moore used the symbols found within the 14 Nations to make flags similar to national flags used across the world. For example we see a constellation of stars in his Kamilaroi flag that represents the Seven Sisters Dreaming, a constellation also recognised by others in the mythology of the Pleiades.

When installing and making use of the flagpoles within the Great Court at the University of Queensland the artworks, now identified as flags, had to follow Government protocol. This action meant that some of the flags could not be flown but it also meant that in having to adhere to the protocols the flags were elevated to recognised symbols of nationalism thus realising the artist’s vision.

When Tandanya curator Troy-Anthony Baylis took delivery of this case of flags he no longer had to follow protocol but could display the work in all its glory. As you entered the space the two largest flags not only made you look up but as you moved into and under the full exhibit you became sheltered under this imagined nationhood. Whether seen through the eyes of gallery visitor at the opening, or while attending the Tandanya Spirit Festival, or within a scholarly visit by university students the flags took on new meanings, freed from flag protocol and Eurocentric dominance. These playful constructions could speak within the language of symbology unfettered, speaking back within the bounds of semiotics, transforming themselves into a mythological knowing as objects imagined; as neither true nor false.

School children sitting patiently listening to a floor talk put their hands up in unison wanting to imagine their own flag designs. University students were challenged to think first of the meaning of ‘‘nations as imagined communities’’ as described in Race and Ethnic Relations edited by Farida Fozdar, Raelene Wilding, and Mary Hawkins; and then of the hidden language of symbology that transcends mere signification with its fullness of meaning and thus to be carried away – as French Semiologist Roland Barthes described – by myth and to open a dialogue to challenge colonisation and nations imagined by the coloniser. Moore’s work is therefore raised into the possibility of nationhood.