When the ‘‘Commemorative Digger Statues’’ were unveiled on Sydney’s Anzac Bridge in 2000, it went unnoticed to the mainstream that they were both white men. In fact it was taken as a given that it should be so. But a significant number of Indigenous Australians participated in World War I. Equally little known, and even more seldom discussed, is that the possibility of getting killed was the only pretext by which they could leave Australia. As non-citizens and classed amongst flora and fauna, Aboriginal peoples were not allowed to carry a passport. The grimmest irony of all is that they were defending the countries that came up with the very imperial system that had decimated them. War indeed stalks the colonised history of our Indigenous history like a phantom: war for oppressors, war amongst themselves, war for rights and recognition – and the intense mourning over death, over forgetting, over neglect.

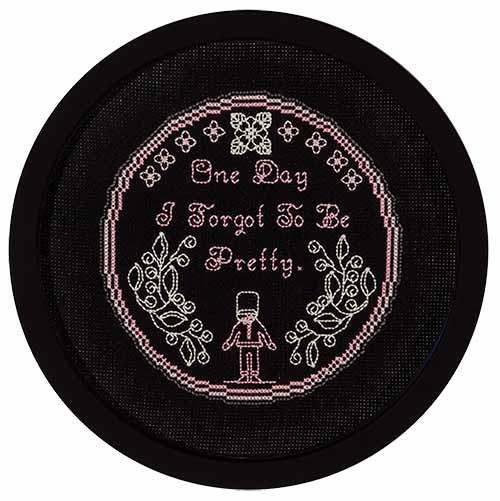

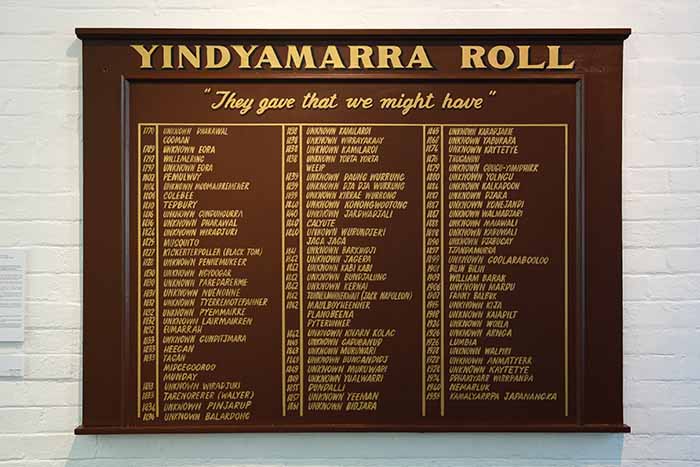

Hence the title of the exhibition, (in)visible, curated by Yhonne Scarce and Meryl Ryan in consultation with the Aboriginal Reference Group, a moving if not harrowing exhibition by contemporary Aboriginal artists dealing with the sadness, anger and ambivalence of the legacy and the continuing onus of war as it relates to them. On entering the exhibition, one was confronted by the now notorious bronze bust of Captain Cook with a balaclava by Jason Wing. Behind it was a wooden honour roll like those found in RSL and sports clubs commemorating former winners or the dead. But instead, Amala Groom’s Yindyamarra Roll (2014), remembered the many lost language groups as a result of the innumerable frontier massacres in the last two hundred years.

In flouting an august and conservative memorial convention, it served as a dry rebuke. Complementing this work nearby was the Poppy Wall Project for which local Aboriginal people designed and made paper poppies which gallery attendees were encouraged to inscribe with personalised messages of remembrance or condolence, and affix to the wall. Significantly, these poppies, although outlined in orange, were a pale yellow, metaphorically drained of blood.This transitional space led to two installations by Julie Gough, including Shadowland (Time Keepers) (2014). In this work, a line of branches jutting from the wall, bore small cut-out figures dangling from copper chains, as if hanged at a lynching.

Equally haunting was Judy Watson’s Salt in the Wound (2008–09), an installation featuring a strange elongated shape in red ochre on the floor, topped with salt. To the side was a small barrier of suspended sheaves of brush, and on the wall was a configuration of disembodied ears. The brush symbolised the windbreak that the artist’s great-great-grandmother hid behind during a massacre at the hands of troopers at Lawn Hill in Queensland in the 1880s. The peculiar shape of the ochre is explained when realising it describes, in uncomfortably enlarged form, the bayonet wound that Watson’s relative sustained while escaping. Meanwhile the ears are like the trophies of the killers, but also the inept receptors of lost voices.

Tony Albert’s triptych of young Aboriginal men with red targets painted on their chests, Brothers (Our Past, Our Present, Our Future) (2013), was hung near a procession of five oversized bullets (from the 2014 Babana Bullets Fundraiser), each painted by a different artist, including Vernon Ah Kee and Megan Cope. In a case nearby was Archie Moore’s paper work General Sanders vs Colonel Saunders (2013), prompted, or provoked, by the knowledge that not far from the gallery is a KFC complex, boasting to be the largest in the country, built on a cultural site important to the Awabakal and Worimi people. With the same irreverence, the artist fabricated fast-food-like from a book recounting the Anzac campaign in Gallipoli.

I write this a week before the centennial Anzac celebrations, knowing that an exhibition such as this is low on the political agenda – the worse for us, yet the silences just seem to get louder and louder.