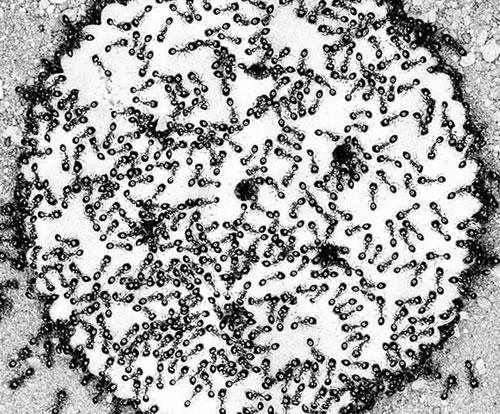

Marina Strocchi was attracted to Central Australia after seeing the work of an artist who represented the heart of the continent from the inside. It was Johnny Warangula Tjupurrula, A Bush Tucker Story (1971) that transfixed Strocchi, fascinating her with its skeins of shimmering dots and shrouded ancient signs. Months after her enchantment, Strocchi rolled into Glen Helen Gorge, where she met an old man, who introduced himself as Johnny W. It was only later that she realised that this disheveled character was the creator of the work that had affected her so profoundly.

Significantly, the meeting occurred where a red cliff face diverts the flooding force of the Finke River, a location long-favored by artists and the site of many cross-cultural encounters. Marina Strocchi A Survey 1992-2014 traces Strocchi’s journey from her accidental meeting with Warangula to the present.

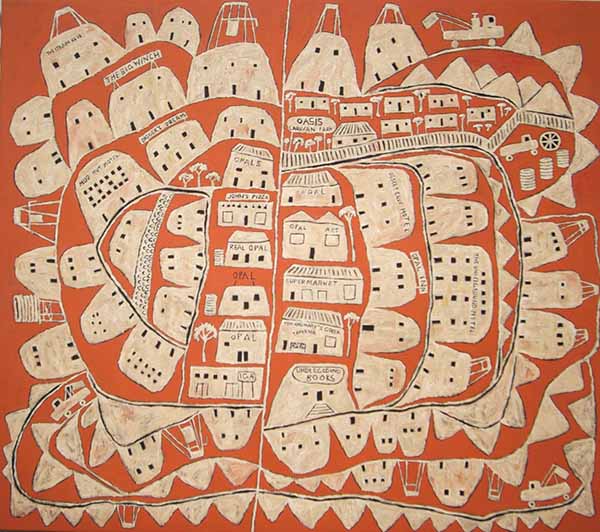

Following various formative experiences, she was tasked with establishing an arts centre at Haasts Bluff, on the Western perimeter of Arrernte country, a region regularly visited by Albert Namatjira. While bedding down the Ikuntji Arts Centre, Strocchi took advantage of quiet moments to paint the extraordinary topography surrounding the community, unaware at that time that she was representing the same sites that had inspired Namatjira. These modest works form the prelude to the survey. While they are tentative first impressions of a monumental terrain, they capture the essential mass of the country. Moreover, they convey a yearning to be embraced by the land. The horizon falls away in subsequent works, as the artist steps into vibrant country, rather than viewing a ‘‘landscape’’ from a single fixed point.

In spite of being located in the Australian desert, Strocchi remains in touch with the masters of modernism. The artist makes this point explicitly in The Kitchen (2002) where instead of books on cooking, her shelves reveal ingredients for making art: COBRA, Egypt, Fairweather, Ikuntji, Klee, Larwill, Matisse, Modigliani, Morandi, Papunya Tula, Picasso, ROAR, Tuckson and Williams. At its best, painting is a conversation across time. And Strocchi’s work is flavoured with influences drawn from distant artists whose work reflects many lands. Her disarming generosity, perhaps inherited from her father’s socialist politics, has grown through familiarity with the approach of Indigenous artists.

The two largest canvases are most memorable. The artist refers to Top End Scrub (2000) and Top End Mangroves (2011) as ‘‘field paintings’’, and they appear to be propelled by familiarity with Fred Williams, but without his stodgy formality, for they encompass a comparable vast purview with dancing vegetative figures of the Australian bush.

It is now more than 80 years since Namatjira painted his first landscapes, and there is a growing catalogue of images of Central Australia. It is into this rich mix that Strocchi’s oeuvre has been stirred. If we were in New Orleans, the mix would be called a ‘‘gumbo’’ but as her paintings were created in Arrernte country, the best term is ‘‘kere-kwatj’’ (meat-water) or stew. Strocchi is a serious painter who creates accessible, enchanting works. The survey at the Araluen Arts Centre reveals her as an important participant in the unfolding representation of Australia’s achingly beautiful heartlands.