Sprawling theatrically through the basement galleries of the Art Gallery of South Australia, The Black Rose is Trent Parke’s gesamtkunstwerk. Seven years in the making, with the exception of Bill Henson’s 2005 retrospective, probably no other Australian photographer has ever shown at this scale. But it presents a dilemma for the reviewer. Autobiography is a vulgar way to understand art, yet here is an exhibition that begins with a diary entry.

Entering through a fairytale-like gothic montage of silhouetted bats and birds, a video of the artist relays the primary plot: Parke was twelve years old when his mother died from asthma, he was alone with her at home at the time, and he dealt with this ‘‘defining moment’’ in the only way he knew how, by blocking out his entire childhood. Since the laconic sound of the artist’s voice echoes throughout the room – which also includes a gold-framed archival photo of his mother on a merry-go-round – it is impossible to view what follows without recourse to this underlying trauma.

The glowing metal of a playground slide, interiors of a childhood home in Newcastle, images of his children being born, even a strand of his mother’s hair – everything is haunted by this loss. It’s the anchoring discourse, supported by a sprinkling of stream-of-consciousness wall texts from which we also learn that Parke took up photography using his dead mother’s Pentax. In short, photography – its capacity to memorialise life’s great and banal moments, and its uncanny ability to mark the melancholy passing of time – is explicitly cast as a medium for catharsis.

We should be sceptical of therapeutic justifications for art. It’s the work that matters, not the artist’s life. And yet here these two things are so obsessively and energetically entangled that it makes little sense to even try to separate them. Parke is Australia’s only member of Magnum – the prestigious agency known for globetrotting photojournalism – but the only voyage here is one of self-discovery. A paean to his family and setting in suburban Adelaide, Parke describes the project, which started as a diary entry, as the sum of everything he has tried to do as an artist.

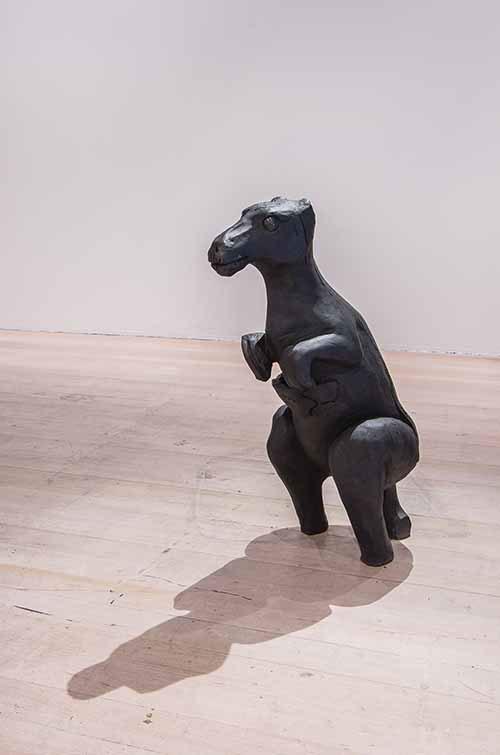

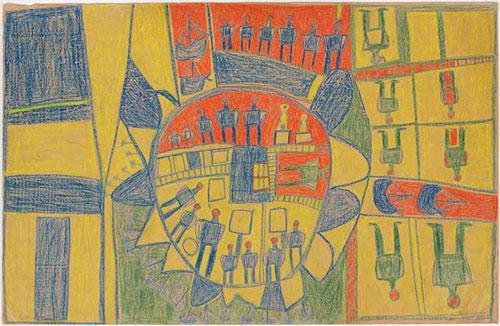

The installation plunges us into his psychological universe, with dark walls and dim lighting. Unashamedly wrapped in mysticism, the exhibition also includes dirt swirls, tarot cards and accounts of Parke’s dreams. Testing various photographic formats and techniques, he clearly works intuitively, searching for coincidences, recurrent motifs and patterns. With such grand themes as birth, death and fate, the results are inevitably mixed.

The metaphors and juxtapositions are occasionally overstated, and some work verges towards the self-indulgent (such as a fetishistically reconstructed darkroom with Parke’s own face in the developer). Some series feel tangential, or like ideas half-started. And yet the whole experience is punctuated by little revelations and epiphanies. Deploying film cameras and an anachronistic style of raw personal documentary that evokes Robert Frank (but also, at times, Roger Ballen), he mines his repressed childhood memories through black-and-white images and a characteristically dramatic use of light and shadow.

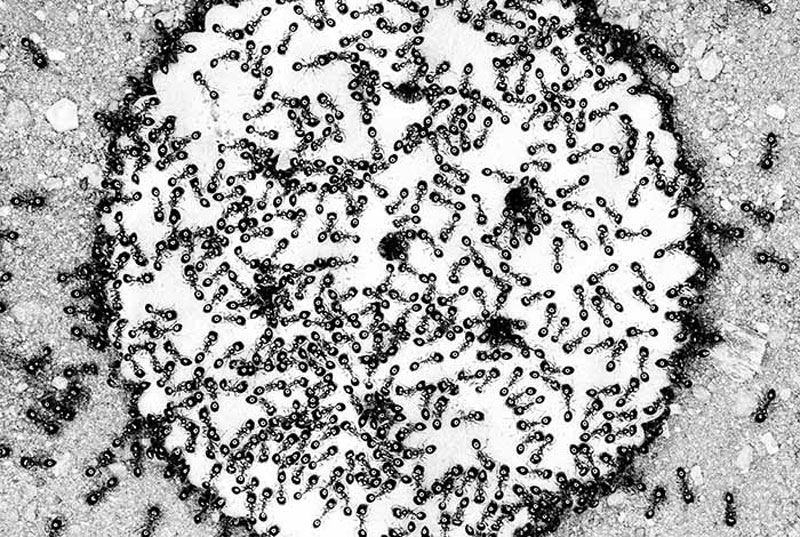

Heavy flashlight pierces the darkness of the Australian bush to reveal untold images of animals – dogs, rabbits, moths, snakes, birds, rats – which function, in their dying or dead state, as a metaphor for the human condition. The coast reveals fish, turtles, crabs, a shark and children – a Tim Wintonesque ode to beach life. The best, most disarming images have a Surrealist quality: a letterbox crawling with ants, an ashen landscape with faint cows’ eyes lit up by flash, granulated street portraits and so on. Although The Black Rose lacks the tight coherence and social critique of Minutes to Midnight (2005), Parke’s road trip around Australia, the exhibition confirms his place as an irrepressible photographer with a singular, if unfashionably Romantic, storytelling sensibility.