In 2013, seven artists spent three weeks together as artists in residence at London’s Freud Museum, his last home. Curator, organiser and artist, Andrew Nicholls, identified Freudian themes in the work of this otherwise disparate group, presenting the results of their individual investigations in An Internal Difficulty, as part of the 2015 Perth International Arts Festival’s Visual Arts Program that will also be touring WA with ART ON THE MOVE.

Many of the artworks illustrate, mimic or otherwise refer to items in Freud’s collections of prints and antiquities, his theoretical propositions or facts about his personal life, often in combination. Nicholls, for example, in his photographic collage called A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière, Pierre Aristide André Brouillet, 1887 (2015) has switched the gender of the patient in Brouillet’s original, (a print that Freud owned), as well as the setting so that it is a male nude standing in Freud’s study in the contorted pose thought to typify Hysteria.

The exhibition is enriched by knowledge of Freud’s life and work. The necklaces that comprise Nalda Searles’ Puabi’s Gift to Sigmund (2014) are a case in point. The artist has included artifacts like those collected by Freud in two of the strands as a gesture of empathy with his delight in such objects. One necklace is a string of small rocks collected by Searles over 30 years, each with a naturally occurring hole. This work embodies the obsessiveness of collecting, with each stone tempting us to interpret its strange biomorphic shape.

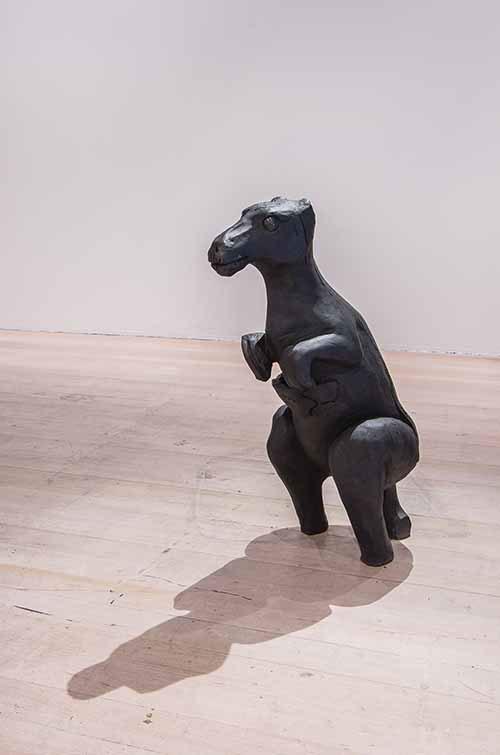

Searles’ Vagiali Figure (2015) is astonishing. A vulval form, made from the artist’s own hair stitched with cotton, cradles a carved wooden female figure from Papua New Guinea. Lying along the vertical crease in the hair mat, the figure’s open legs envelop a shadowy recess, hinting at a hole before the undulating ridge of the figure’s torso leads to its bulbous head. Searles has combined the elements in such a way that they are sublimated to become a powerfully evocative form before their individual qualities resurface; a transformation analogous to the undertow of the subconscious and the return of reason.

The fringed couch cover in Susan Flavell’s I am Filled with Objects (2015) was given to the artist by her mother but is now covered with embroidery, scrawled text, scraps of junk jewellery, buttons and hand-made porcelain medallions. In the dim light the clusters of letters dissolve before words emerge and the small forms refuse definition. The resultant ambiguity imbues the artist’s interventions with the same arcane potency possessed by Freud’s antiquities.

Thea Constantino’s beautifully rendered drawing of Freud’s oral prosthesis, Monster (2015), offers a direct experience of the uncanny. Parts of the object, the teeth for example, are familiar, yet other parts evade identification making the drawing simultaneously realistic and surreal; an utterly compelling combination.

While each artist has pursued their own lines of enquiry, certain themes and motifs recur through the dark and labyrinthine exhibition: gender, sexuality and desire; the monstrous and the uncanny; the fragility of order; and of Freud himself in his final years.