The library as we might recognise it had its beginnings in the Italian libraries of the sixteenth-century. A nobleman such as Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest would have built and maintained such a library to collect and secure documents, significant books and curious objects. His library, like its imagined version in curator Juliana Engberg’s exhibition Tempest at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, is likely to have also contained significant objects related to discovery, philosophy and nascent scientific theory. Reflecting the spirit of optimism and enquiry of the time, they could be maps, navigational instruments, globes, records of encounters with the “new” World as images and tales relating to wondrous and exciting journeys and bizarre environments and their equally bizarre inhabitants – a Wunderkammer of sorts. Within this space a large shard permanently installed containing a range of objects of curiosity as well as a work by Patrick Hall, Hollow Vessels (2012), also functions as a Wunderkammer but on a much smaller scale, now so neatly absorbed into the curatorial concept of Prospero’s Library.

This is our entry into the complex, rambling and expansive experience that is Tempest, an exhibition which explores a range of interpretations of that theme from the specificity of its basic definition in (mostly) maritime contexts to a much deeper and richer evocation of states of experience and psychic and emotional conditions. The external and internal aspects of “Tempest” sit side by side and often overlap in the grand sweep of this comprehensive show.

As Engberg makes clear in her catalogue essay, she was not seeking to “re-tell Shakespeare’s story, nor illustrate it, but to respond to the various ingredients of the play with genres and episodes that imagine a super-fictional account of The Tempest – open to interpretation and imagination, as its author intended”[1]. In this, they have succeeded admirably. This methodology is entirely appropriate given that The Tempest is perhaps the most open-ended of Shakespeare’s plays inviting various readings and often contested interpretations.

As one of a declining number of Australian institutions that serve as both a museum and art gallery, resident curators have at various times sought to utilise the collection of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in a series of often interventionist exhibition projects as well as broad-ranging social history shows, with varying degrees of success. Tempest takes the idea of such projects to another level, borrowing works from other collections, as well as commissioning a few works for this exhibition. Objects and artworks (many of which have not been exhibited for years, if at all) have been drawn together in a context which can cope with their diversity and curiosity. The show extends virally throughout the complex, from the Central Gallery into The Argyle Galleries, The Hunter Gallery and even into stairwells and as subtle interventions in the Decorative Arts and Colonial Gallery spaces. Elements of the collection which are not part of Tempest equivocally hover at its edges, conceptually entering a shadow space around the curated elements.

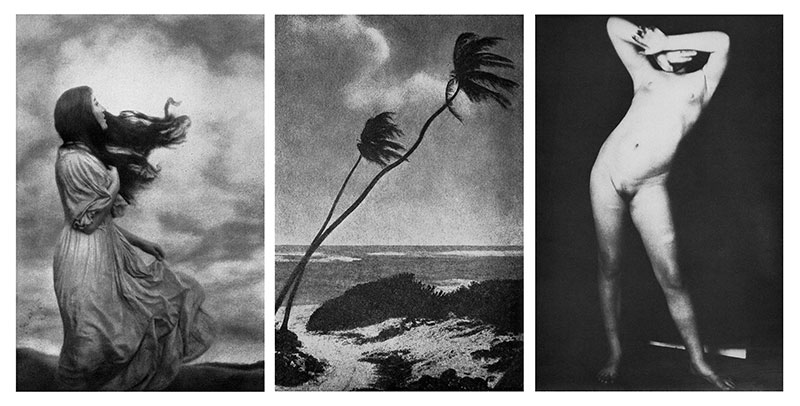

The works of Tacita Dean are well represented and the artist’s work Event for a Stage “Storm, Storm, Storm” 2014, is cited by Engberg as a key trigger point for the exhibition. Dean’s script starts with an encapsulation of the beginning of Shakespeare’s Tempest. Pat Brassington’s three- panel work Untitled (1989) from a major show of Brassington’s work that Engberg curated for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne, completes the connection, suggesting a new narrative around the three images: a windswept girl, an island palm tree and an hermaphrodite, resonating serendipitously with layers emerging from the text of the Bard.

Curating this show over a two-year development period cannot have been anything but marvellous fun. There is alive in the result a sense of joy, awe and wonder in the works themselves and in their interactions. For sheer scale, Dean’s expansive blackboard storm drawings, (When I first raised the tempest, No 17599), Rosemary Laing’s weather #4, Valerie Sparks monumental wallpaper collaged visions, Prospero’s Island, which evokes the start stormy entry into Shakespeare’s play in a specifically Tasmanian setting, and video works like Fiona Tan’s A Lapse of Memory are big, immersive and compelling. But the tiny, intimate works, like the sweet little watercolour of the Tasmanian Spotted Handfish (1864) by Louisa Anne Meredith, interwoven between them, are also engaging, mysterious, precious and entrancing.

John Glover’s studies of the sea at Scarborough from 1804 have probably never been exhibited at all but they have been awaiting this context, enabling Enberg to incorporate many jewels from the collection aided by TMAG Curator Jane Stewart and the curators of the various scientific collections. The premise of this exhibition has inevitably cast a very broad net, yet it all hangs together surprisingly well and forms a rich visual exposition of the many layers of such a potentially difficult and exponentially enlarging concept. This is no runaway train or glorious grab-bag, as it could so easily have become in the hands of a less astute curator faced with such a massive field of choices.

The flow of the exhibition is marvellous. The balance of interior and exterior, the quiet and the roaring, the sombre and the downright amusing (Rodney Graham’s cynically slapstick Vexation Island from 1997), the deeply mysterious, magical and beautiful (Mariele Neudecker’s 4.7km = 3 Miles or – 2.5 Nautical Miles from 2009), the haunting and emotive (Fiona Tan’s video Nellie from 2013), is well orchestrated to make The Tempest a rich and absorbing experience for the viewer, pushed and pulled, overwhelmed and intrigued, and allowed to enter imaginatively into the works and their implications and possible interconnections. One senses that this is an experience which can be entirely unique for everyone who engages with it, no matter what age or background. This was borne out in my visits to the show over three days.

Scale and intimacy evoke aspects of the Sublime. Artists whose work is often loosely described as sublime usually depict a situation which evokes it and therefore the Sublime is a function of referral to the presentation of a situation as the actual trace or context which evokes it (in the work of Turner, Friedrich et al), but it rarely evokes a direct encounter with the Sublime, which Thomas Weiskel characterises as the suspension of all known relations. Somehow, the totality of this experience seems to do just that. The swing between these states of awe and enchantment is at the heart of the rhythm, as an active and dynamic experience of “Tempest”. I spent the best part of two days immersed in the exhibition and can’t wait to return, there is just so much to see and so many levels to move between. The heart-rending ennui and anxiety of works like Nellie remain in the heart, quietly resonating long after the initial engagement with the work.

That this show makes real sense in Tasmania is no accident. Many years ago, Engberg curated an exhibition for Chameleon that explored aspects of the Tasmanian Gothic. This was a convenient conceit in which to engage with the history and mindset of this place. Dark Mofo, the Winter Festival which has brought national attention to Hobart, is an entirely appropriate context in which to explore many of the themes present in Tempest and to celebrate through ritual and elemental forces, things which have lain long-buried in this place. Tasmania’s coast is littered with shipwrecks often of ships like the Neva which made it all the way from Cork, Ireland only to be wrecked in Bass Strait, so close to its destination with its cargo of mostly women and children.

The experience of Tasmania is often dichotomous, at once beautiful and soul-opening but also fearful and menacing. Nowhere is this better described than in the jail journal of Irish patriot John Mitchel whose Tasmanian experience has been published as “The Gardens of Hell”. In it Mitchel shifts from a light and melodious prose when describing the landscape to a flat terse language when bemoaning his sad fate at being incarcerated in this place. This collision of opposites exists in Tasmania still and we hold both within us simultaneously. Tempest accepts and even revels in this strange equivocal balance and it is reflected in the range of works in the exhibition, including individual works like Sparks’ Prospero’s Island, in which the left panel depicts the storm and the forbidding coastline and the right reflects the bucolic peace of a quiet safe cove. Yet the two are joined, they are both as true as each other, and they form an uneasy coexistence. The shadow of one is always behind the reality of the other.

The extensive public program for Tempest included floor talks by Juliana Engberg, an artist’s talk by Mariele Neudecker, an Australian premiere screening of Tacita Dean’s Event for a Stage at the State Cinema, open rehearsals and two performances scheduled for October and November of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in the museum’s Bond Store by local theatre company Blue Cow, and of course a great program for children based around the idea of a quest through the gallery, among other activities. This exhibition is also significant in that it brings many departments of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery together to work in a collegial manner to produce something special and truly unique. Having spoken to some of the team who brought this vision into reality I think the following quote from a wall text is a relevant conclusion here.

Naturally men are drowned in a storm, but it is a perfectly straightforward affair, and the depths of the sea are only water after all.

Virginia Woolf

.jpg)

Footnotes

- ^ Juliana Engberg, Tempest, exhibition catalogue, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, 2016.