In Nicolas Roeg’s 1971 film Walkabout a lithe Aboriginal hunter emerges from the intense glare of the sun, his long stride dotting the mountainous dunes. A mirage, a necklace of flyblown goannas hangs lifelessly from a rope around his gracile hips. According to the film’s internal logic, he is a mysterious stranger who speaks a language known only to himself. A fanciful reimagining of first contact, Roeg’s film slips into a hallucinogenic trip – as though the viewer has been intoxicated by some potent bush narcotic. From the Western position, this encounter in the desert is strange and frightening: a collision between the original and the alien newcomer, it is saturated with longing; bodily thirst and hunger conjugated with sexual desire. If we perceive the distant we can imagine all kinds of mirages, dreamlike illusions of the mind.

Any publication that purports to be global is clearly making a big if not unreasonable claim. I want to issue a disclaimer: from my perspective, this edition of Artlink magazine was never intended as a survey of global Indigenous art but more a broad attempt to focus inwardly on the outward gaze, the simple uncomplicated act of looking outwards, of perceiving the distant. I have been challenged on this point. I would say that no one owns the term global and we might attach it less amplitude.

This Indigenous edition of Artlink – the sixth – is driven by the need to widen the reach, the retinal surface, the eyeline, of the magazine to include investigations into the largely undocumented recent history of cultural exchange between Indigenous populations here and overseas, of intercultural dialogues about colonialism and the global environment, the ‘‘reframing’’ of world culture to include Indigenous perspectives and the transnationalism that underpins so much artistic production today.

Artists generally aspire to reach across the borders of nation states to communicate with audiences at a deeper conscious level: beyond politics, language and culture into the visual, the global imaginary. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists deliberately exceed the fixed category of ‘‘Australian’’. As Michelle Evans suggests in her incisive critical text in this issue, we are already perceiving the distant – as we have always done. The outward gaze is nothing new. Indigenous people in settler colonial societies such as Australia are global in that we are taking a broader view, reckoning our own place and that of others, just as Roeg’s hunter did in his fictional encounter with the lost children in the desert.

As communities in Western Australia are forcibly closed down, on the pretext that they exist as a lifestyle choice, few could be surprised. The former Howard Government minister Amanda Vanstone characterised such communities as ‘‘cultural museums’’. Despite their extraordinary cultural production and economic output as centres of Aboriginal art, they were recast as fiscal basket cases, and therefore lifeless and moribund. The Northern Territory Emergency Response was considered by some as a cynical attempt to assume control of Aboriginal-owned land, using the protection of vulnerable children as a hollow pretext. It seems that there is a price to pay for infrastructure in remote communities, the Australian Government is unwilling to pay for the basic services which other citizens take for granted.

My co-editor Djon Mundine and I conceived of this issue and its global focus independently of each other. I was living temporarily in Shanghai, the world’s largest city by population. At the time I was working as an intern for a collective in the art district in Moganshan Road. Although I saw a lot of contemporary Chinese art, I felt an absence: do we exist? In a controlled, monolithic state that restricts access to Internet sites as banal as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter the idea of a global art reaching beyond national borders became more urgent. Art – the articulation of a creative impulse – is a political act as much as it is social and cultural. It can empower its maker or express political agency through social mobility despite extraordinary attempts by the complex machineries of state control worldwide to mute, suppress and destroy the human voice. In states where a form of liberal democracy is practised and where freedom might include the shaming of racial and ethnic groups to ‘‘closed’’ societies where there is apparently no freedom there are degrees of control, silence and censorship. I remember feeling a sense of freedom in China. I was unknown; whoever I was, my cultural identity did not seem to matter. Censorship is a fundamentally political act that is executed at minute levels on a wide spectrum: in close personal relationships; at the local, community level; moving on to a national level; and from there to the global, international level. In my opinion, silence is a language.

At the same time, as I unexpectedly returned to Australia, my nephew Bodhi was in the latter stages of his gestation. I had witnessed the incessant power of his heartbeat – the urgent pounding of life. Unfortunately, around the same time, our father also experienced the near-fatal effects of aspiration: when ingested fluid rests on the lungs. Suddenly the need to focus on anything but the immediate seemed extremely foreign and almost obscene.

Just as the forced closure of Aboriginal communities might seem an unrelated event affecting remotely located people, I was triggered into a wider understanding – why am I and my Aboriginal family living in our place any more entitled to basic services than our countrymen in remote areas living in their place?

My former ABC Radio colleague Ursula Raymond was at Uluru to produce a radio documentary about the 10th anniversary of the handback in 1995. She captured a brief but extraordinary moment of cultural exchange that still resonates. As his largely white audience tried vainly to attempt to enunciate the nasalised term anangu (person) a frustrated senior traditional owner tried in response to assert that anangu was a human, not racialised term. He was insistent: ‘‘You – me – Anangu!’’ As heretical as it may sound today, twenty years later his meaning was clear: we are all one people. In the east we have differentiated, racialised terms for the invader, in Bundjalung we call them dugay. Pale intruders who mark territory and gesticulate wildly; their wide, flourishing movements – bewigged in frock coats or bearded in skinny jeans – pretending as if they own the place.

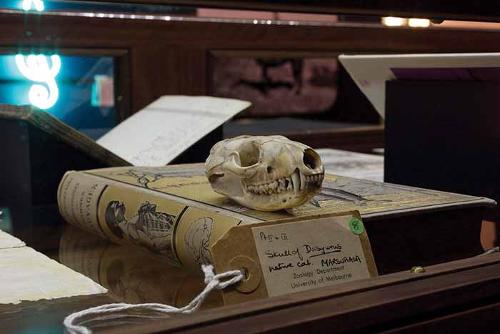

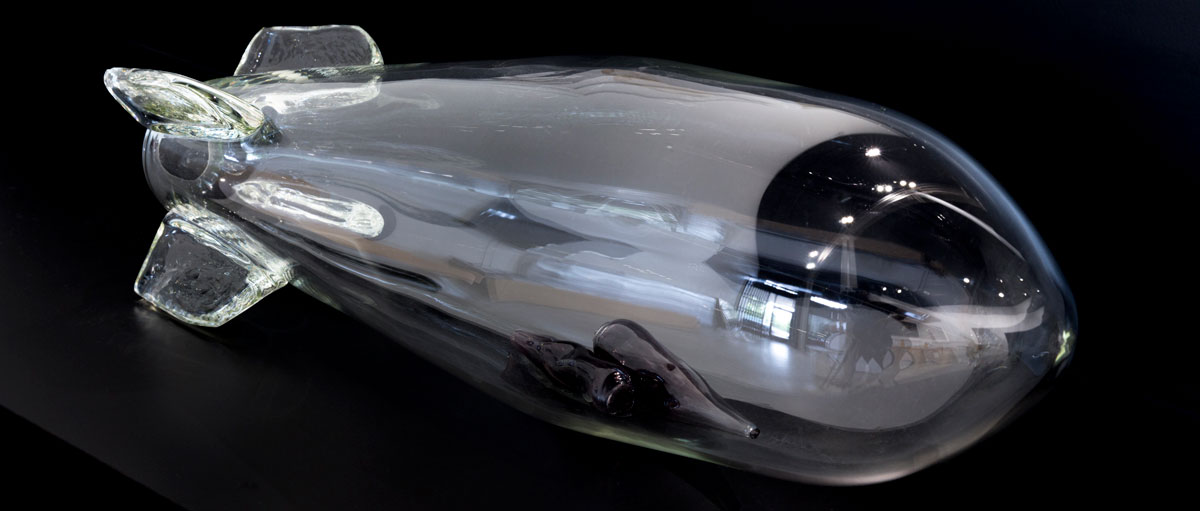

Artists are amongst the most fearless people I know when it comes to confronting the big issues, like the elephant in the room. Yhonnie Scarce’s most recent works exhibited in Hong Kong and Berlin begin a global dialogue about the effect of the British nuclear tests at Maralinga; a reverberant echo, in what is otherwise yet another great silence in Australian history. The horizon line, broken by a towering vertical cloud, its radioactive plumes were dispersing on the hot wind. The artist is compelled by the blind contempt for human life, and the deceit practised by governments here and overseas against their own populations; the hand-blown glass bombs holding withered, elongated forms represent an undeclared civil war against defenceless citizens. A contemporary artist who works with glass, Scarce also produced a series of sensuous bush foods – a signature – painted with targets in the colours of the British flag.

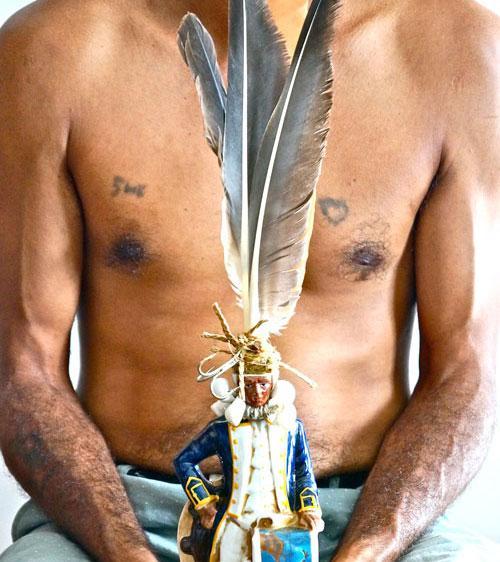

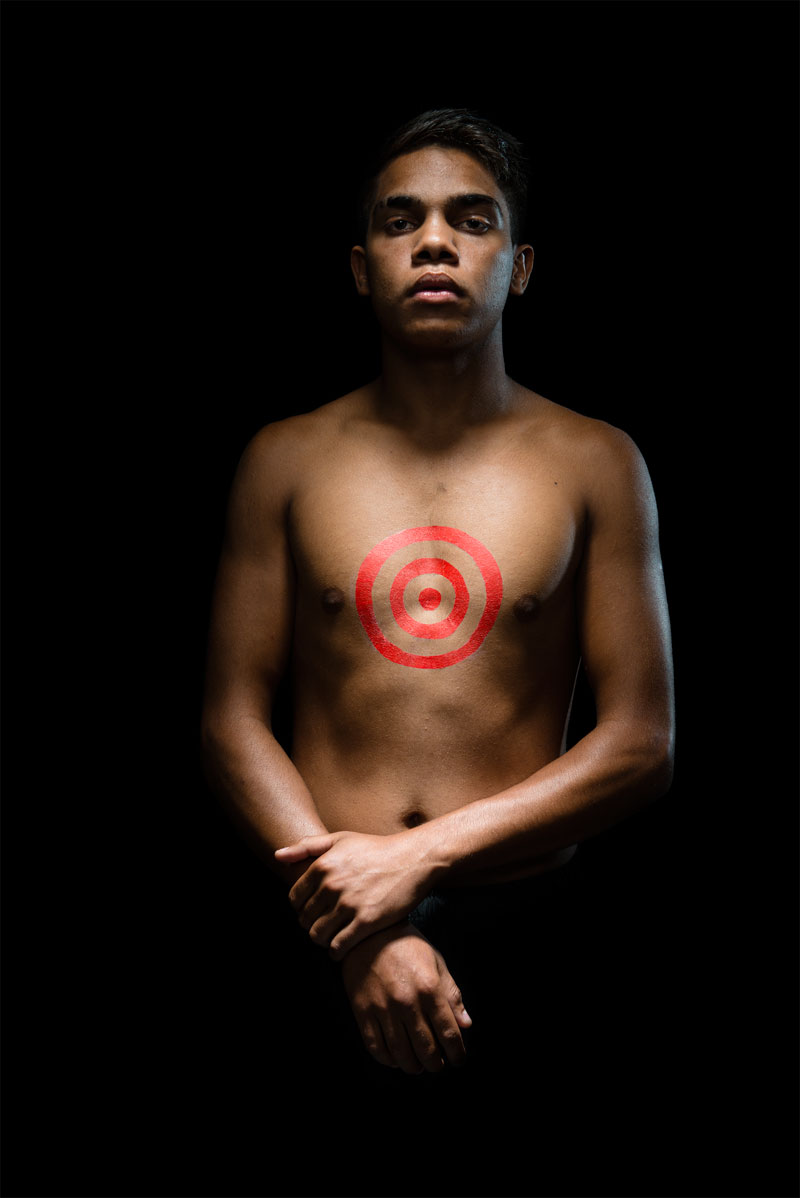

The target (a trope in the visual language of Richard Bell and Christopher Pease) recurs in the Brothers suite of photographs by Tony Albert which Scarce selected for exhibition – as co-curator with Meryl Ryan – in (in)visible: the First Peoples and War at Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery. The racially profiled ‘‘brothers’’ are civilian targets, ordinary citizens who are subject to extraordinary surveillance. Racial profiling has the effect of criminalising anyone unfortunate enough to have been born ‘‘non-white’’. Driven by social media, the Black Lives Matter campaign in the United States was in response to a wave of police and civilian killings of unarmed, racially profiled, innocent black men and children (in the case of Trayvon Martin). It was preceded by the Idle No More movement for Indigenous rights in Canada, which grew from the activism of three Aboriginal women and a non-Indigenous ally. Both movements have resonance in Australia. A local movement within the borders of a nation state had become transnational and intercultural: that is, global.

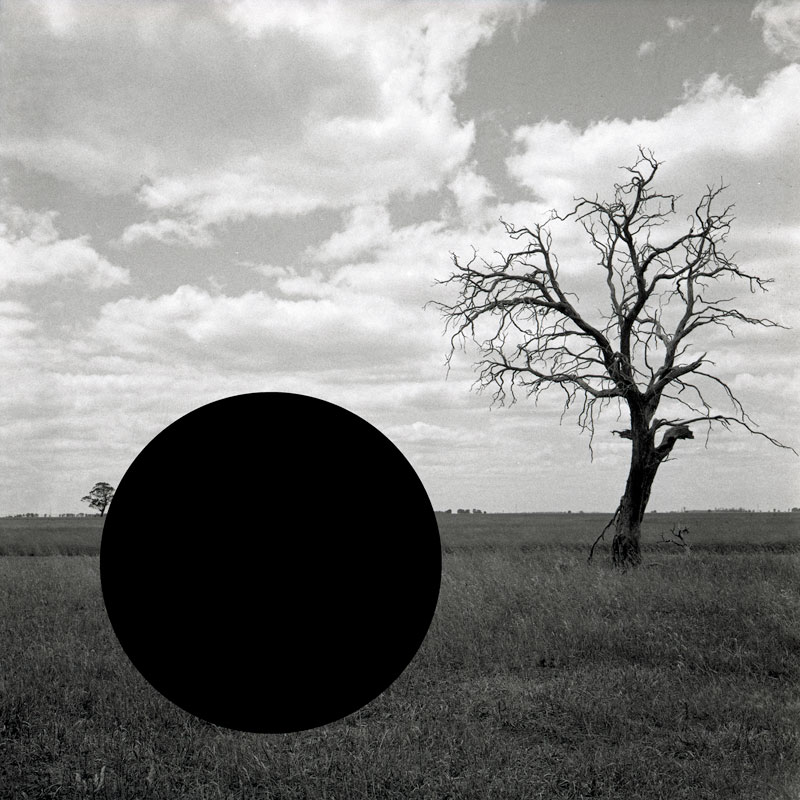

James Tylor’s perfect voids, which appear like Dr Who’s tardis in the haunted landscape are either suffocating black holes retreating into the past or flicking camera-like apertures that glimpse the promise and hope of an unburdened future. Are we victims of a haunted, overburdened past that we cannot change or lithe actors in a glinting future that we can control – even in a small way? How we apprehend, reconcile or deal with the past and how we confront the future is a global, human question.

An aside: the new rehang of some key works from the superb Indigenous collection of the National Gallery of Victoria leaves me cold. An executive decision to relocate the permanent gallery for the exhibition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art from the highly visible ground floor to the upper third floor of the NGV Australia Ian Potter Centre in Melbourne’s Federation Square represents another dispossession; cynically forced out to make way for an industrial design/car show, the relocation seems to mirror a darkening political mood.