Sound and installation artist Gary Warner has cast a wide net in his curation of Fieldwork, a group exhibition incorporating artists with a research-based practice of working in the field, mostly in rural or wilderness locations. Regrettably, it could be one of the last shows in the magnificent SCA Galleries at Sydney College of the Arts, as its parent body, the University of Sydney, negotiates closure of the college. Outside the gallery, protest banners around the college are in synergy with the activist agenda of one of the major installations in the exhibition, While We Sleep, by Williams River Valley Artists Project (WRVAP), a call to action against the neo-liberalist economic policies of the NSW State Government policies on mining and agriculture.

Many of the artists in Fieldwork sourced the data for their research directly from the field, highlighting the natural world and natural capital with an ecological sensibility. Catherine Woo had formerly engaged the weather as a creative agent in an expanded painting process. For Fieldwork, she took large-scale rubbings of the flat rock tessellations of Tasmania’s Pirates Bay. Titled Interface, this frottage project was described in the exhibition catalogue as a partnership with the local geological formations, a form of “drawing with geology”.

Not all the artists in Fieldwork directly sourced their own data: John McCormack and Gary Warner accessed the sonic records of ornithology for a quivering marginalia (Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab or Ornithology), creating their own unique field. This consisted of a sound work that positioned its visitors inside a bespoke built geodesic dome. A multitude of tiny speakers distributed ornithological samples mixed with data of the human voice. The field existed nowhere in Nature, even though its elements were taken from specific actualities.

In works by Barbara Campbell and Helen Grace, the methodology of fieldwork was foregrounded. Impressions on human agents were dominant in Grace’s video-journal of a train journey on the Trans-Siberian Express. Ten passengers were given diaries in which to handwrite their experiences, and snatches of text, selected by Grace, were overlaid on the moving-image footage. The fieldwork was very much her own construct, an assemblage of moving train, diaries, passengers and landscape.

Barbara Campbell worked the other way. Responses of her human actants were driven by the behavior of cattle and birds in the landscape. Working in the Yangtze delta mudflats of Asia she was struck by the natural frottage of drawings traced out in the mud by the imprints of oxen pulling a plough as they turned and changed direction at the end of each row. Even though it could be argued that human agents were directing the plough, these boustrophedon – or bi-directional written texts (from the Greeks who first gave a name to this process) – are created through animal agency.

The struggle for dominance within the field manifested in several more works. The principal actant in MERAPI: Stories from the Volcano – An Interactive Documentary by Josephine Lie was a recently erupted volcano. Even though the work consisted of video interviews by those who had experienced its wrath, the dominant player determining the action was very much the volcano.

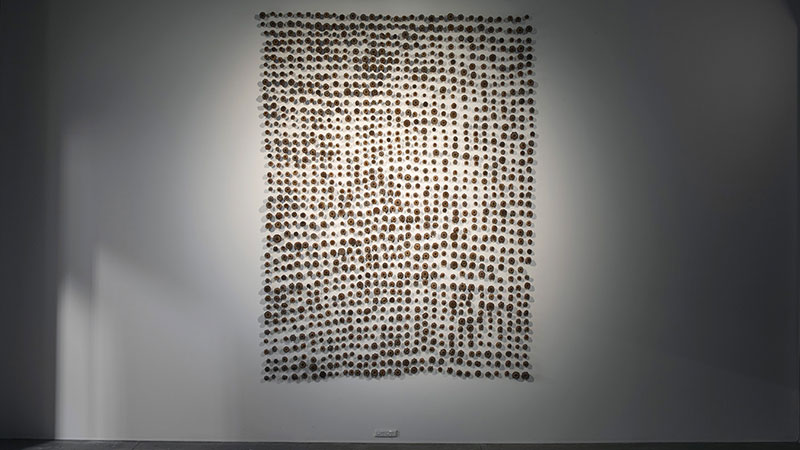

On the side of human agency, Maria Fernanda Cardoso worked with women from the Tjanpi desert. With their assistance she collected hundreds of distinctive seed pods from a tree in the red desert country, Eucalyptus macrocarpa, whose pods resembled brown roses. As an invited guest, working within the group, her fieldwork reflected the habitus and her place within the socius. When laid out in modernism’s classic grid, the seed pods rippled with the natural variations of dot paintings, as if something of the sacred relationship to country had been transmitted through working in the field. Cardoso had come into country ”proper way” and this respect was reflected in the larger field of relations between people and land.

In a painterly vein, Fieldwork included a trio of painter–photographers. Carl Warner recreated a nineteenth century ”Claude glass”, a small black converse mirror which nineteenth century artists used to distort the field of Nature into painterly images of landscape (Error and Illusion). His rainforest video periodically distorted and then recalibrated like those employed in casting painterly perceptions over nature. Eugene Carchesio used observations of the world, and his own mental abstractions, as fieldwork for his series of small abstract paintings mysics and prophets. Field photographs of bush landscapes also became the erased substrate for Jeff Doring’s large semi-abstract paintings.

Since the early 1990s Jon McCormack has been receiving international accolades for his delivery of highly refined digital code. His digital gardens, evolving in real time, featured in Mediamatic, alongside Benjamin Fry’s Tendril. For Fieldwork, McCormack takes colourfield painting to a digital high with a subtle work of self-changing bands of abstract colour. Each line is programmed to read the colour values of adjoining lines that mutate.

Jeff Doring, After a fire the bush shoots with fresh green, 2013–16. Photo: Ian Hobbs

In sum, Fieldwork is a broad show that admirably delivers with fidelity to concept. Some gallery goers might find it academic, even dry, in its rigorous foregrounding of matters of method – a little too research-based in tone.

Less illustrative of method, the collective installation of work by the Williams River Valley Artists Project (WRVAP) directly engages in the fieldwork of rural activism in protest at state government policy that prioritises short-term profit over long-term goals: destruction of prime agricultural lands and water in the name of Big Coal. David Watson employed a professional sign writer to detail the names and environmental crimes of the global corporations: Kepco South Korea (Bylong Valley), Yancoal China (The Drip on the Goulburn River), Whitehaven Coal UK (Maule’s Creek on the Liverpool Plains), Rio Tinto UK (Bulga and Super Pit), Peabody USA (Wollar). In plain unfired clay, Toni Warburton laid out the letters A VOID on the floor to signal the vast toxic voids left in the earth after mining. In general reference to the ravages of the extraction industries, Suzanne Bartos wittily repurposed 44-gallon oil drums as Buddhist prayer wheels. A collective installation of children’s toy graders and bulldozers, in extraction industry colours of yellow and black, threw up a sinister shadow play over the landscape. Juliet-Fowler Smith chalked a sad local list on the blackboard. Courtesy of local activist Bev Smiles, the names of families were crossed off as they were forced to leave the district.

WRVAP were a perfect fit to the Bourdieu reference in the catalogue: addressing the socio-spatial arena in “which people manoeuvre and struggle in pursuit of desirable resources” according to the rules of the field. Of all the works in Fieldwork this best illustrated the hierarchies inherent in the way fields relate to each other within the “larger field of power”, as stated in the catalogue. The WRVAP installation directly addresses the current protest of Peter Andrews, inventor of Natural Sequence Farming, an acclaimed agricultural technique proven to drought-proof farmlands and restore soil health. With ten of his thoroughbred horses, Peter Andrews is squatting Tarwyn Park, Bylong, in defiance of its impending destruction by Kepco Coal.