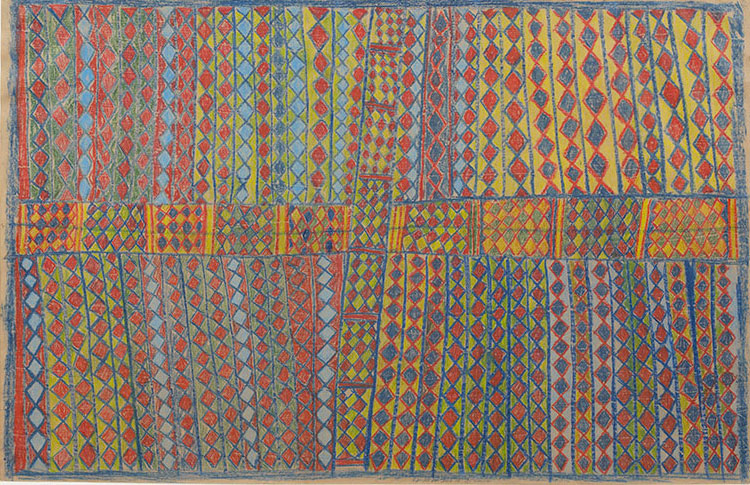

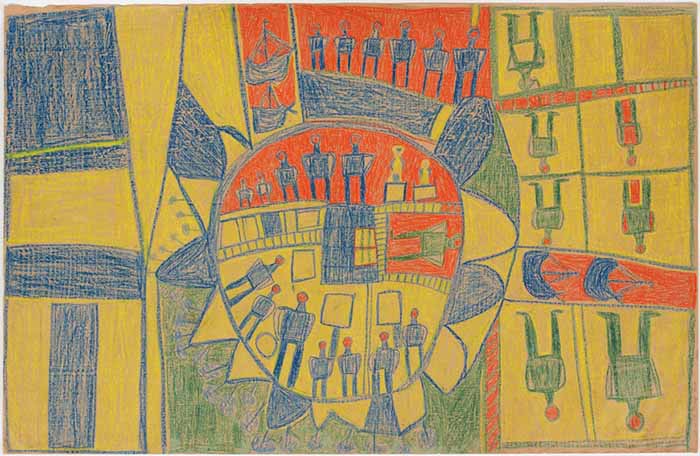

The visually arresting Yirrkala drawings on show during the 2015 Perth International Arts Festival at the Lawrence Wilson Gallery, University of Western Australia, were made by the senior leaders of the Yirrkala community in 1947 through their meeting with the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt, who encouraged a new, highly transportable artform using crayons on brown paper. The 365 works produced immediately became a unique form of artistic achievement, also as significant cultural documents of Yolgnu wisdom and law.

It is hard not to be effusive about the works in this travelling exhibition curated by Cara Pinchbeck. Mesmerising, confident and forward, these works have not lost their potency despite being made over 70 years ago. This is largely due to the innate artistic vision and strength of the visual currency of the Yolgnu artists who have translated the methods of working on bark to the vastly different material of paper. In many of the drawings, where finesse was required to explain or detail particular aspects of a narrative, pencil has been used to outline objects. In some works there are finely detailed notes in pencil in a bottom corner, in others numbers to pinpoint important sections, written by the Berndts themselves.

Drawings by the Marikas, a now famous Yolgnu family, feature heavily, and there are many significant works that reveal recurring areas of narrative importance. Untitled (1947) by Mawalan Marika looks like a mind or cognition map of sorts, revealing important Yolgnu relationships and connection to particular sites, as does Myth Map (1947) by Mungurrawuy Yunupingu, and Map of Yalangbara (1947) by Mawalan Marika.

A number of objects from the Berndt Museum collection that relate to the Yirrkala drawings are also on display, as well as a video work and a series of drawings created by Year 12 students from Yirrkala school who visited the Yirrkala drawing exhibition at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory. These extras add depth to the exhibition that may support the interpretation of the drawings but to my mind they also serve to ethnologise them. Having seen the exhibition in Darwin where the drawings were exhibited entirely on their own, I feel that that display was all the more powerful for the stand-alone contemporary context in which they were then placed.

There is always a tension in interpreting historical works in a contemporary context, and if they were produced within an ethnological framework this increases the difficulty. There are few didactic or extended labels within the exhibition space, but the included objects beg the question of whether the viewer is being asked to consider the works as contemporary works of art or as interesting historical documents? Perhaps both?

Any outsider coming to this show can, through the knowledge of the Yolgnu artists embodied in each work, have at least a superficial understanding of some of the intricacies of relationships between Yolgnu people and towards Country; an understanding that completely negates the idea of Yolgnu culture and law at Yirrkala or indeed of any Indigenous community as being a ‘‘lifestyle choice’’. However, it’s not essential to appreciate these truly unique and frankly beautiful works on paper.