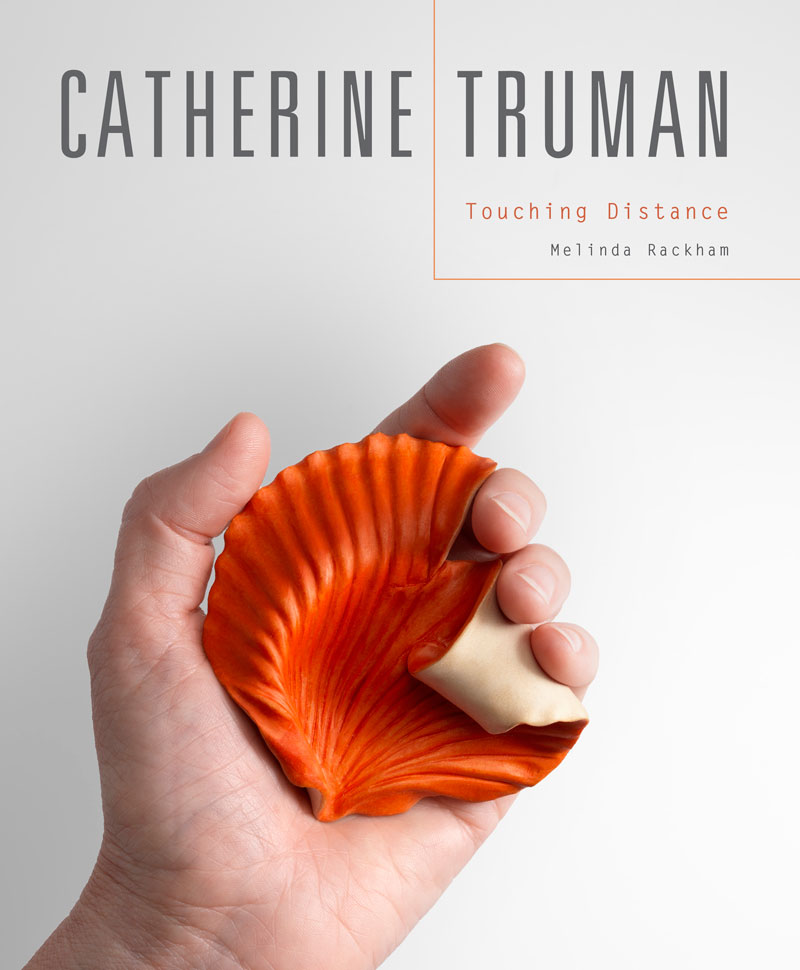

The SALA exhibition by Catherine Truman at the Art Gallery of South Australia is as mesmerising as it is frustrating to behold. Her beautiful and delicate objects are made for the eye and for the body, and the greatest temptation is to pick them up, touch them, feel the material in your hands. For Melinda Rackham, the writer of this year’s SALA monograph, it is this relationship between the maker, the body and material that shines through in the work of Catherine Truman.

Rackham’s approach is to create a story world around Truman that is as much a biography as it is a history of jewellery and object-making in South Australia from the 1970s to the present day. Accompanied by luscious full-colour photographs by Grant Hancock, the monograph is a beautifully produced object in its own right, documenting the life of the artist from age seven to now. Rackham has chosen to create the monograph as a series of chapters, which reflect a chronological timeline but also a personalised and intimate life chronology, captured poetically in the titles that include “grounding influence”, “under the skin” and “the shape of things becoming”.

Truman has always lived in Adelaide, where she studied at the School of Design, now part of the University of South Australia. She has had a lifelong passion for tactile and miniature worlds and we are given an insight into her childhood by the seaside at Glenelg, where she became a “a curious observer of the shifting beach landscapes, coloured skies and vast seas that saturated her senses”. She recounts peering as a child at the netsuke (small carved Japanese figurines) at the Art Gallery of South Australia and being drawn into their narratives.

It is no surprise that Japanese techniques and carving styles became highly influential in her work. Truman’s experiments in the early 1980s with the seventeenth-century Japanese Mokume-gane metal-working technique offers an insight into her fascination with materials. Like the netsuke, Truman created small insect characters in metal alloys that could be held in the hand, turned over and studied.

Together with Anne Brennan and Sue Lorraine, Truman established the renowned Gray Street Workshop (GSW) in 1985. The GSW went hand in hand with the dynamic political and cultural environment of South Australia following the years of Dun Dunstan as Premier. Rackham provides an insight into those times and how these young artists were inspired by feminism, re-thinking the female body, exploring radical new approaches to jewellery design and object-making.

It was around this time that the fish motif became prominent in Truman’s work, which Rackham says, “intuitively articulates a feminist discourse of difference in conceptions of ageing and beauty”. Accompanying the text are nine wonderful black and white photographic portraits depicting young children through to elderly women wearing fish brooches and necklaces. There is a great sense of joy in these portraits as if the models are thrilled to be wearing these marine talismans.

from Barbara Macdonald, Look Me in the Eye, 1983.

The GSW gave Truman a springboard from which she could journey into the world to learn new techniques, undertake residencies and collaborate with international artists. Rackham celebrates these explorations by detailing how each experience feeds back into Truman’s conceptual thinking and practice.

There is such a strong sense of respect and admiration throughout the monograph that the reader is given a truly authentic and intimate insight into the artist’s practice. It is this strong sense of authenticity that allows Truman to open up about repetition strain and injuries, with Rackham commenting that, the “resistance of wood and shell were being met with an equal and painful resistance within her body”.

These strain injuries led Truman into a life-changing approach to her work and body, becoming a Feldenkrais practitioner and incorporating healthy practices into her work and teaching. The body form also becomes more prominent in Truman’s work during the 1990s and 2000s, creating small torsos, again the scale of netsuke, that are inspired by a sinewy grotesque body as the way perhaps of negotiating her own bodily limitations.

Rackham also recalls how Truman became more and more interested in the body, its anatomy and essence, which brought the two together through a Synapse Science and Art residency (when Rackham was Director of the Australian Network for Art and Technology). The monograph features documentation from this residency and Truman’s continued exploration of medical procedures and dissection. Her work becomes almost forensic in its interrogation, resulting in jewellery and objects that are organic, body-like and twisted.

This is a glorious hardcover book produced by Wakefield Press and designed by Rachel Harris, filled with memories, images, thoughts and inspirations. Above all, it is an affirmation of the creative journey and the power of art to transform the maker, the wearer, the writer and the reader.

.jpg)