Since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species some 160 years ago, we have taken our time to embrace a logic, previously intuited and more fulsomely lived, that humans are merely one among a number of near relations and companion species on an evolutionary path. This “animal turn” is a belated response to the crisis evolutionary theory has posed for humanism prompted by a growing awareness that every species but our own and those that most tenaciously adapt to our lifestyles is in precipitant decline.

Suddenly it is nature not the monuments to human culture that absorbs us in this task of mourning, anticipating the loneliness that John Berger forewarned us about in his seminal essay, “Why Look at Animals?” (1977). In her overview essay, “Entangled Looking: The Crisis of the Animal,” Creed asks us “to adopt a look of greater reciprocity supporting common histories, origins, sensibilities, desires and (perhaps more diversely inscribed) forms of intelligence.” Creed starts out by addressing animal rights, and the moral cause of mutual respect and empathy based in looking with not merely at animals.

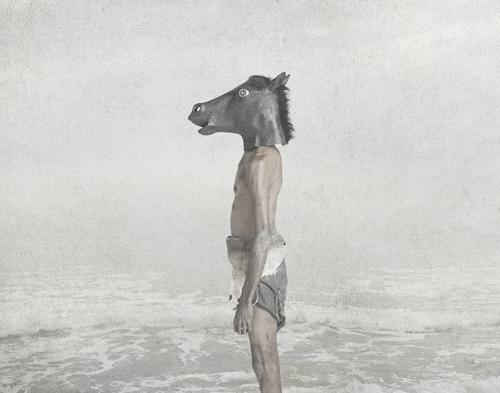

Far from representing an affront it is the animal in us we channel, embracing the difference as the last chain in the logic of inclusivity across all races, creeds and gendered others. As the various artists profiled across these pages demonstrate, a creaturely way of thinking goes beyond imitation as flattery to also question the limitations of what it means to be human, in part to better ourselves. Thus Madison Bycroft takes on mollusc worlds to generate an inter‑species, non‑symbolic eulogy, Lisa Roet sets up a two-way screen in the primate zoo to challenge who is looking at whom for entertainment, Georgina Downey writing on the practices of Art Orienté Objet, Berlinde De Bruyckere and Jenny Watson takes on the burden and the empowerment of becoming-horse, while Ann Finegan reflecting on behoofed experiences as a form of wilful shackling and camouflage takes on the sartorially inspired practices of Mella Jaarsma and Christian Thompson.

In her profile on the 2016 Why Listen to Animals? project by Liquid Architecture, Tessa Laird captures the performative momentum of working with senior Chilean artist and poet Cecilia Vicuña, whose very name is animal (vicuñas are the ancestors of the llama), pointing out as rationale that “they have been around for far longer than we have, and by not listening to them, we are not listening to the part in us that may know how to survive.” What’s more, “they are the masters of the imPOSSIBLE, they learnt how to fly, swim and breathe under water when needed.”

Adaptability is key, as Paul Allatson and Andrea Connor accede in tracking the ibis in the Australian cultural imagination as a bird most likely to survive by feeding off our waste. Humans, like animals who have foraged to survive, have a perspective on going back to basics, meaningful as evidence of shared fates. This is brought home by the moving tribute to Trevor “Turbo” Brown by Christine Morrow, capturing the love, companionship and kinship with the birds and animals the artist painted that accompanied a less‑than-fortunate life in human terms.

Similarly, as featured on the cover of this issue, Hayden Fowler in a remarkable work of virtual reality and live performance, recently presented in a cage at Sydney Contemporary, further privileges the work of bonding with animals to take on what Creed has termed the principle of a “stray ethics,” privileging the co‑dependence between human and non‑human animals at times of threat and abandonment. Responding to the aporia between the bounded and unbounded life, in her article for this issue, Sue Ballard writes, “The cage appears bleak, but the virtual world is filled with colour, light and the apparent splendour” of a landscape imagined through dingo eyes.

As Hayden has said of his motivation to produce this work, “Currently the world is facing a looming death of the ancient in both human culture and our environment, where the delayed effects of modernity and acceleration of technological industrialisation are playing out. We are at a critical tipping point in extinction and the loss of our ancient relationships and physical experience of nature and particularly the wild.” This wild embrace, like clinging on for dear life to a rollercoaster that is the Anthropocene, is one among many compensatory moments of recognition spread across these pages that harness our renewed efforts in consideration of the animals.