Search

You searched for contributors, issues and articles tagged with Activism ...

Contributors

Issues

Articles

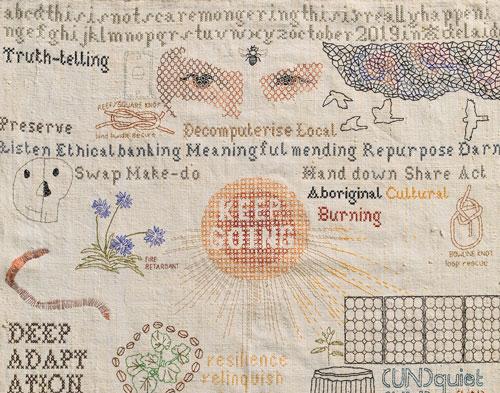

It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

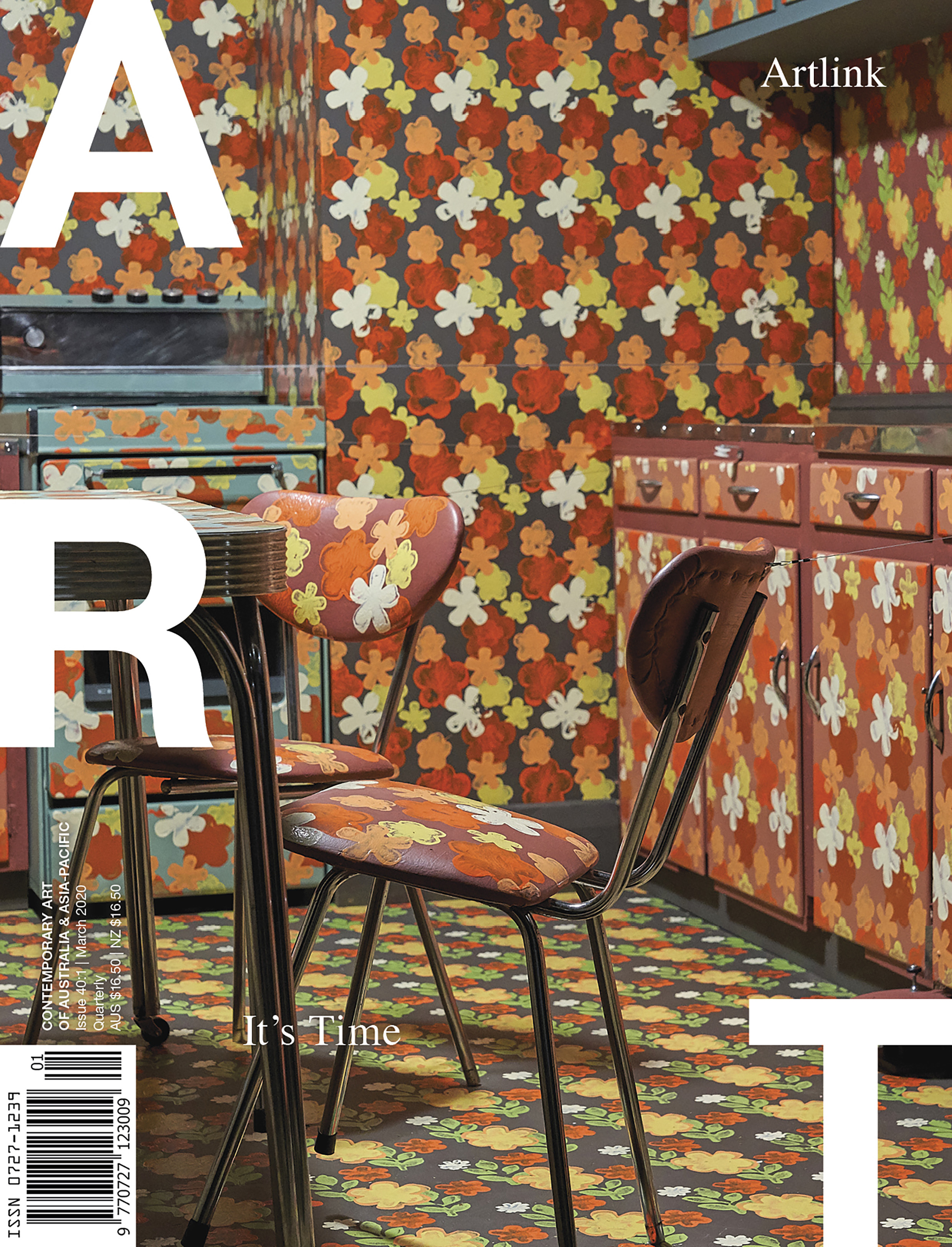

Sometime on from this provocative trueism attributed to Fredric Jameson or Slavoj Žižek, attempting to capture the momentum of the climate crisis and an associated distrust of the ability of governing bodies to tackle the systemic imbalances has proved to be a growth industry for die-hard aesthetes. This is the new normal, a contagious meme, signalling the putative end times.

As Samuel Johnson said to Boswell, “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

I thought of this definitive comment on time as I was writing this article in late December 2019 in the Blue Mountains, in forty degrees temperatures as smoke swirled around outside from fire storms only kilometres away. We had been told to evacuate but we didn’t, we’d been through this before. The car was loaded up, the cats locked in the house and their cages ready to pack and run. But immanent immolation did not concentrate my mind, or only in the wrong way as I compulsively checked FiresNearMe and messaged friends to check they were okay. They often weren’t: several were burnt out, many had life-threatening escapes, and evacuations were commonplace. My friend Ronnie Ayliffe was posting videos of burning trees falling onto the road as she fled her farm and headed for Cobargo, itself already on fire.

[I]t is increasingly clear that there are no topics or phenomena to which a feminist analysis is not relevant—at which point it is useful to consider feminist theory ... as a set of techniques, rather than as a fixed set of positions or models.

The state of the art world and of feminism in the twenty-first century ushers in different ways of doing political activism, cultural work and theory. The intergenerational aspects of feminism and how this has been enacted in the visual arts in recent years represents a refreshing change from earlier perceptions of waves of feminist theory that tended to privilege the new. The visual metaphor of the new wave dashing the old against the shore appears to replicate traditional paradigms in what some have called either an Electra or an Oedipal contestation where the new generation kills the old feminist mother in order to please the father (the academy).

In 2016 the arts in Australia inhabit a dystopian world. It could be described as a place of absurdist contradictions, where only those who have mastered the arcane rules of the Hunger Games have any chance of surviving. Possibly the greatest change is that arts funding is now a partisan political issue in a way that it has not been for some generations. In the past there were concerns about the internal politics of art bureaucracies, but now the allocation of funds to support the arts (or not) has become a party‑political issue. The Commonwealth Government recently presided over the greatest reduction in arts funding in Australian history, but when questioned on this in a public forum, the art‑loving/art-collecting Prime Minister was unaware of the impact of his party’s budgets on the arts. It is probably unfair to blame the current Prime Minister for the devastation that was wrought in the time of his predecessor.

Nearly two decades ago, when artist Rodney Glick and I started discussing the possibility of developing an international contemporary art space in a small country town, people found the idea both comical and intriguing. They laughed when they heard it first but then reconsidered, perceiving a potential beyond the apparent joke. The reason for such hilarity is obvious: contemporary art is so closely associated with the inner city areas that the idea of transplanting it among paddocks and feedlots came across as funny, like a hairy man wearing a tutu.

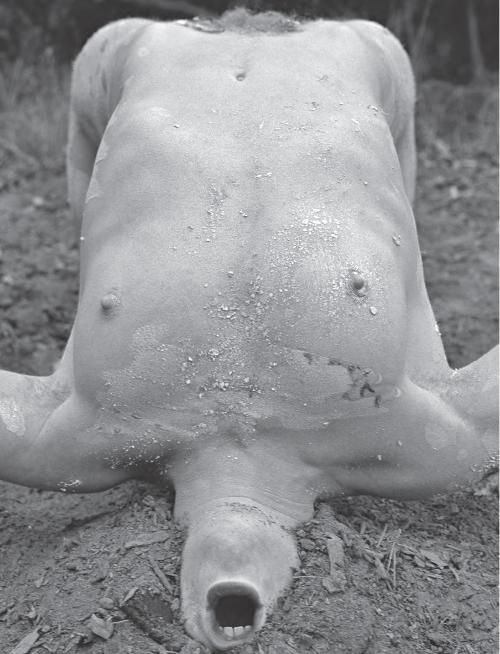

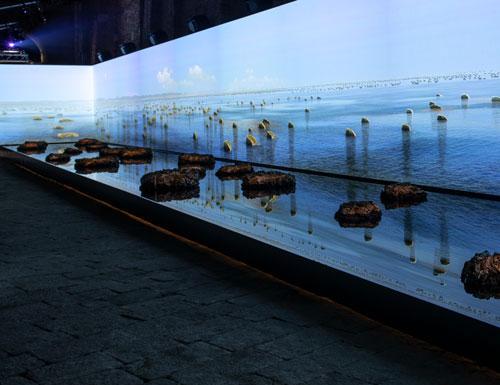

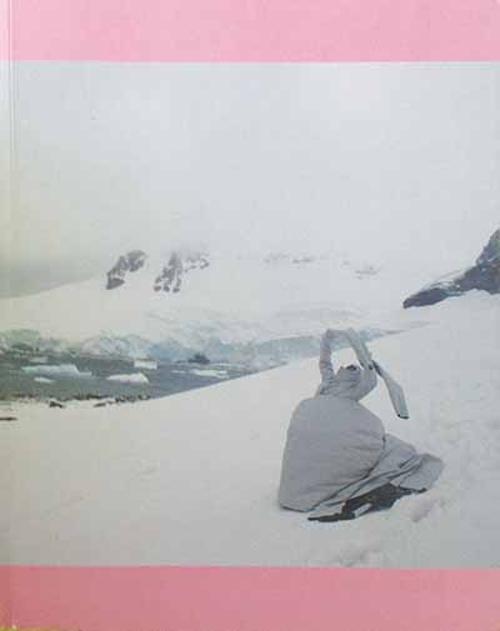

Solastalgia has come to signify distress caused by environmental damage. The term, originally coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht, specifically addressed the condition of existential distress caused by the physical destruction of one’s immediate environment. As the global extraction industries and the financial institutions that bankroll their reach increasingly dominate, with direct impacts on land, solastalgia is fast becoming a common contemporary condition associated with the loss of ground in our occupation of the planet and a general sense of helplessness.

The Palmer Sculpture Biennial is a characteristically transient, remote art event that takes place in the Mount Lofty Ranges of South Australia, some 70 kilometres east of Adelaide. Led by sculptor Greg Johns, who purchased the 163‑hectare property of rain‑shadow country at Palmer in 2001, it has become a place for artistic nomads, who converge on the landscape to create ephemeral and site‑specific art. This unique art event that takes place every two years is aligned with an ongoing program of land regeneration, supported by a community of artists and environmentalists.

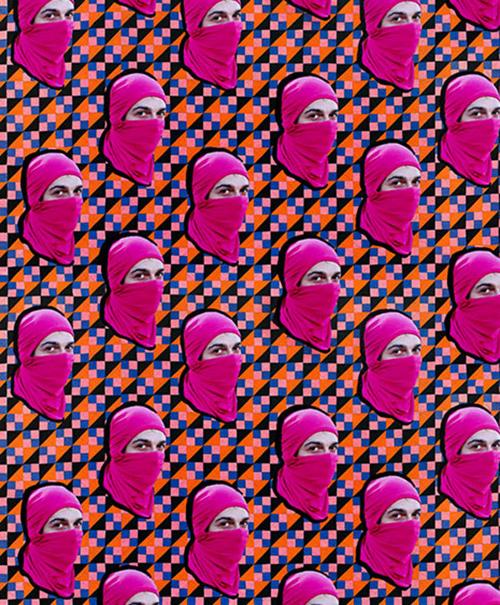

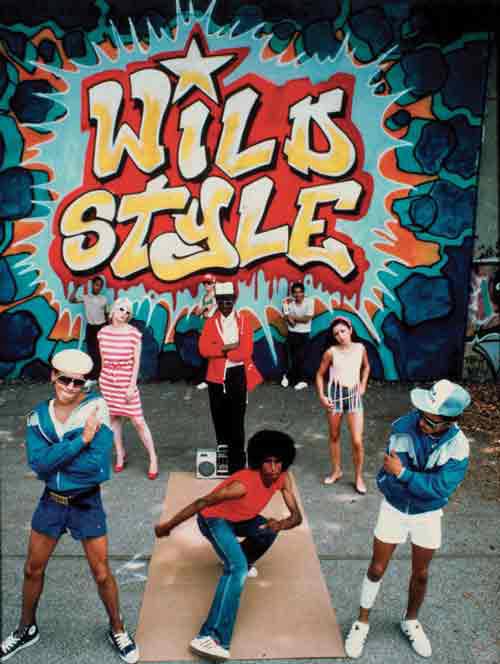

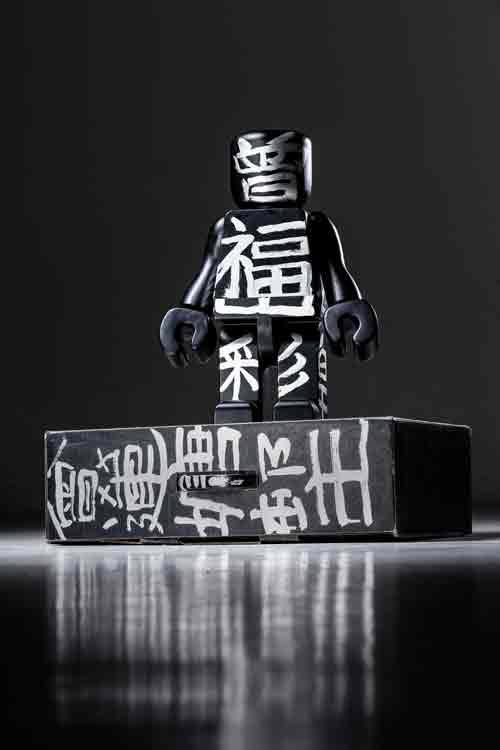

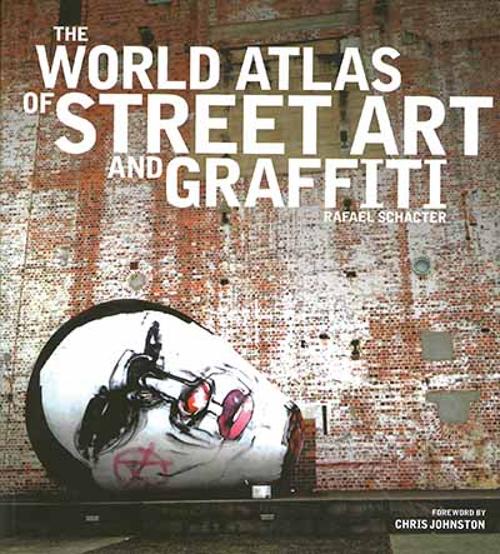

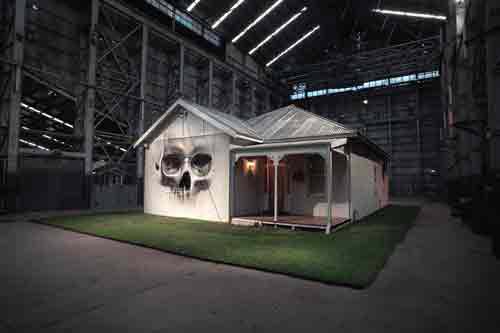

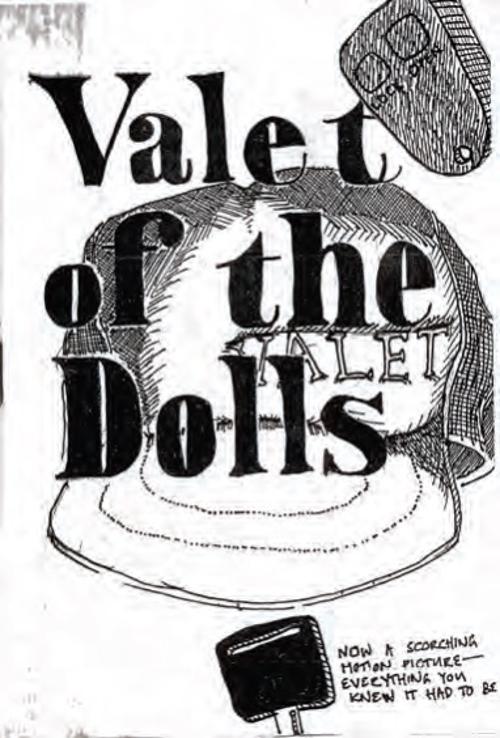

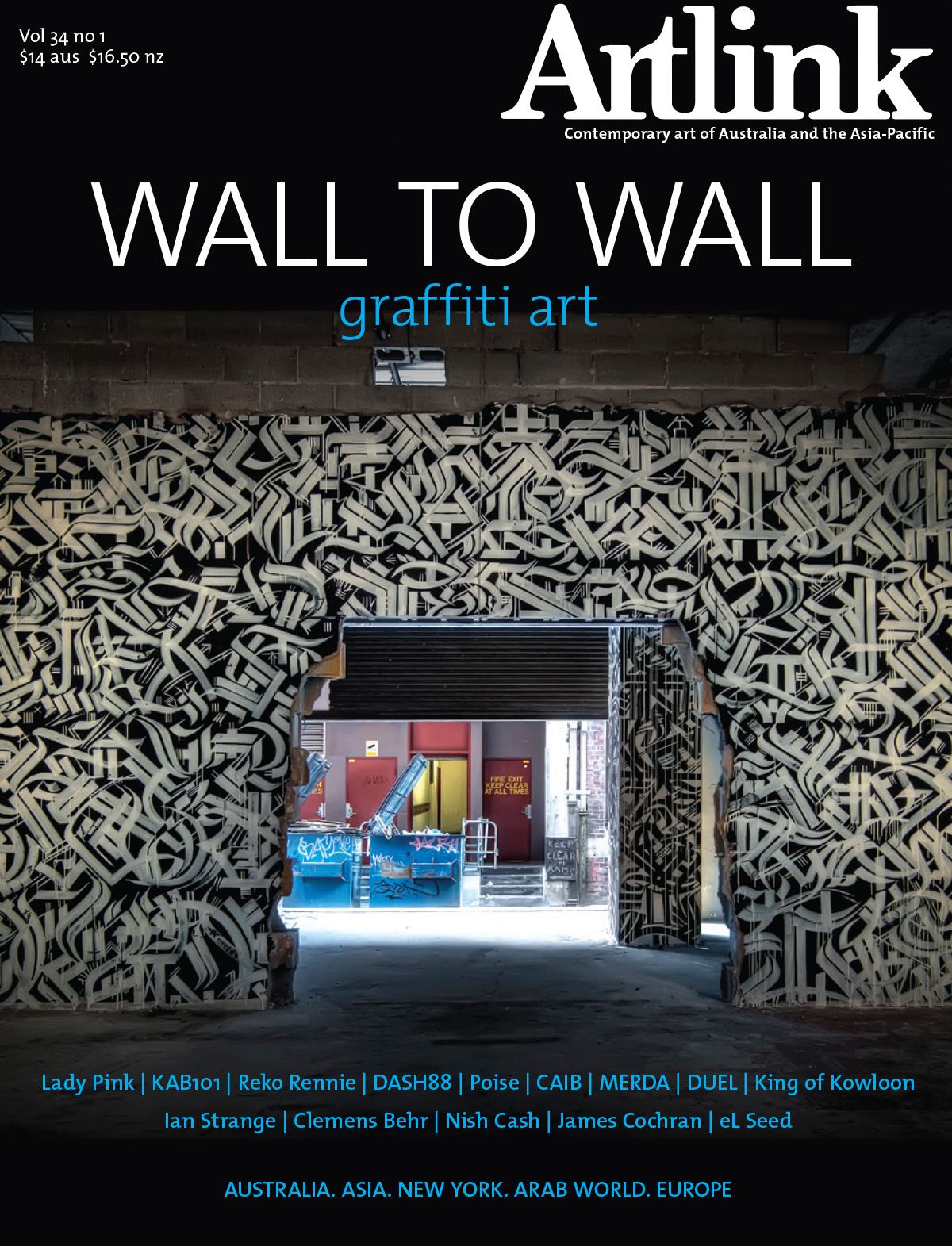

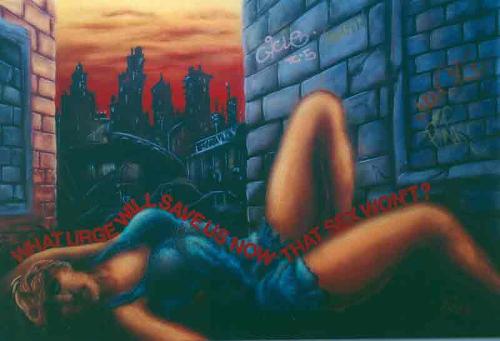

Co-Guest Editor of WALL TO WALL Annemarie Kohn writes about how the seed for a graffiti issue of Artlink was sown, back in 1991 at the Metro nightclub in Adelaide. Twenty-three years later, this edition of Artlink is thought to be the first time an Australian art journal has been devoted to exploring graffiti as a contemporary artform.

Associate Professor Joanna Mendelssohn looks over the last twenty-five years of tertiary art education and wonders where the intake of students from a broad socio-economic spectrum has gone and where the subsequent shrinking cultural conversation leaves Australia?

Professor Pat Hoffie of Griffith University, interviews the two new Directors of the IMA, Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, and contextualises their appointment in the Contemporary Art Space context of 2014.

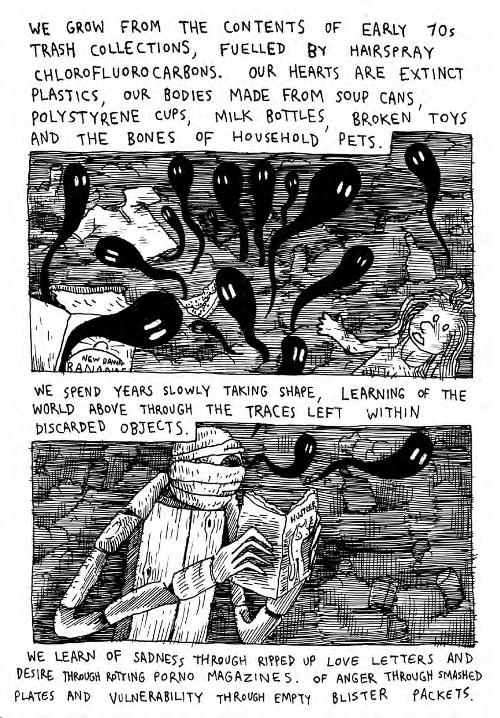

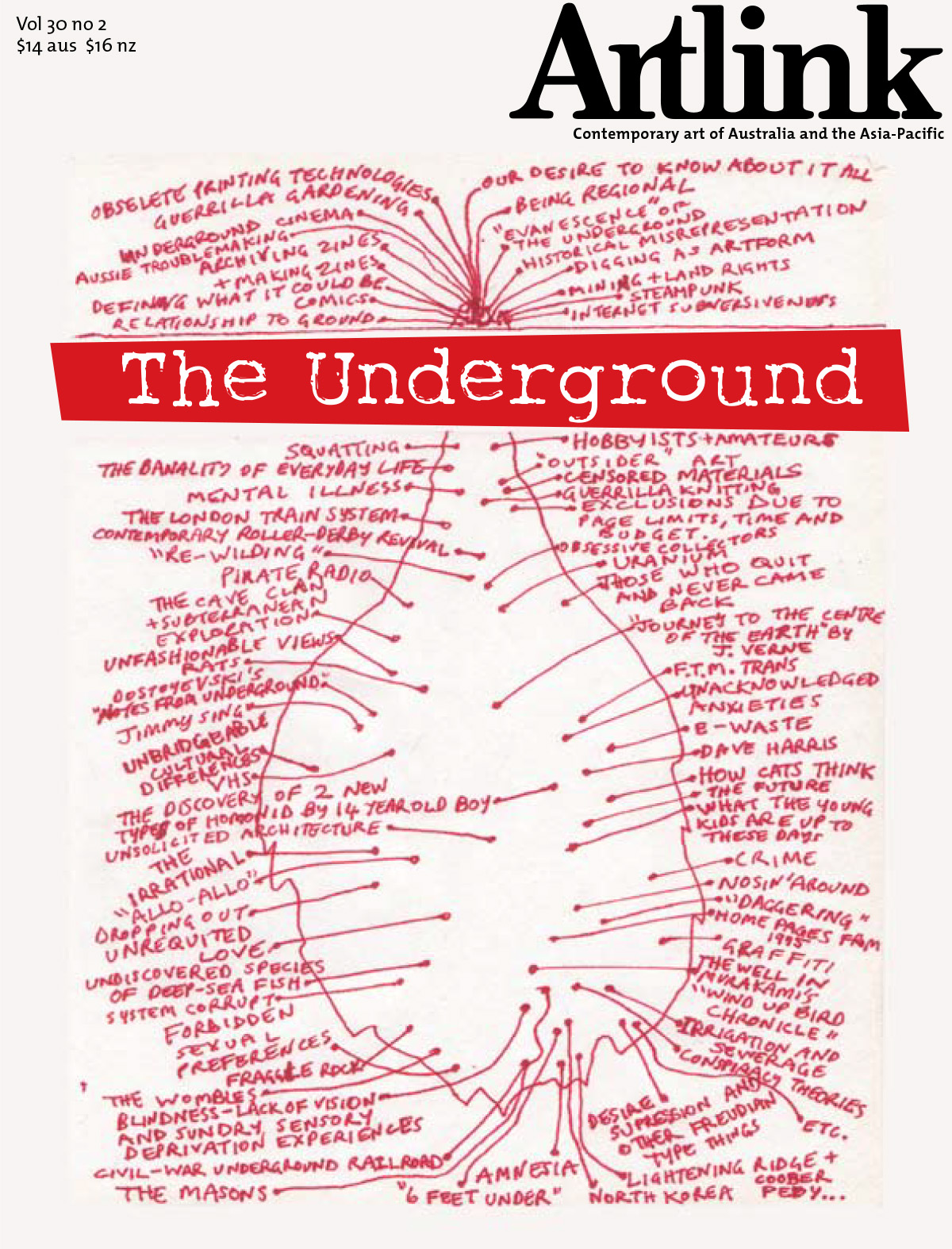

Artist/ writer, curator/designer at the Australian Experimental Art Foundation Teri Hoskin's thirteen paragraphs sum up facts, apprehensions and suspicions about the underground.