Other Homes and Gardens, installed in the Adelaide Central School of Art Gallery during the 2019 South Australian Living Artists Festival (SALA), quite literally rocked my world. This work by Nicholas Folland, reproduced on the cover of this edition of Artlink, is a stage set, a self-destructing machine rigged up on a time loop with wires that pull apart the very foundations as the walls tilt and slide, chairs rock back and forth. It is compelling as scenes of mayhem and chaos always are, and a powerful metaphor for the end of an era of faith in progress, the failed project of modernity. It signals #NoFuture. (You can read more about this work in the accompanying artist profile here.)

This notion that we are in freefall, living on borrowed or secondhand time, based on unsustainable models of production and a reliance on climate-change inducing fossil fuels is extremist but real to many. It is what is driving the Extinction Rebellion and world-wide mass protests. The recent jump forward in the setting of the Doomsday clock at 100 seconds to midnight announced by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists further highlights concerns around the failure of governments to mitigate against the risks posed by climate change, digital disruption and failing peace negotiations that once again raise the spectre of nuclear war.

In roughly the time it has taken to commission and produce this issue, prolonged and widespread bushfires, the like of which we have never seen before, have decimated homes, lives and habitats, shrouding our capital cities in smoke for weeks on end. The bushfire crisis, notably followed by floods, hail, and COVID-19 virus-induced travel bans, introducing further threats. Once the stuff of dystopian fiction, it feels like the Climate Apocalypse is upon us.

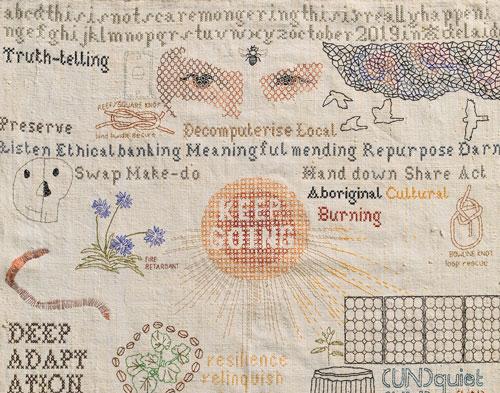

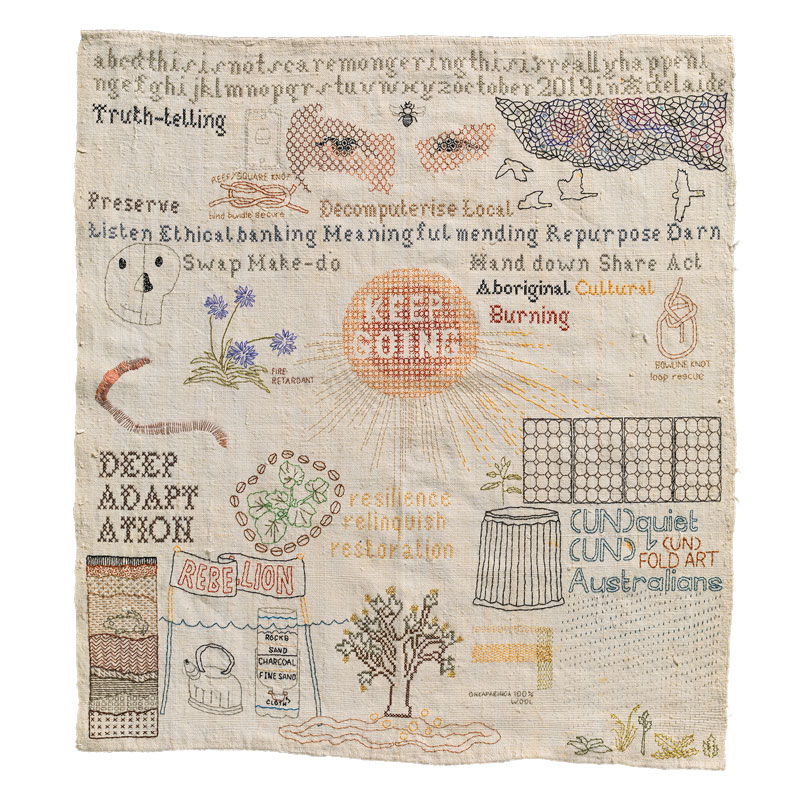

In a heartfelt tribute to the cultural moment, Ian Milliss’s opening feature, “Art in the time of the burning” speaks to this turn. Coping mechanisms and ideas of cultural adaptation are further discussed in Sera Water’s “Crafty prepping”, privileging the restorative agency of slow art and traditional skills in her own craftwork and the practices of Chaco Kato and Rebecca Mayo. The world of the prepper is also championed by Darren Jorgensen, along with a broad capture of the science‑fictional and do-it-yourself technological responses to an increasingly data‑driven surveillance world across a series of exhibitions, films and publications claiming “2019: The year of our cyberpunk future”. This can be read as a sequel to his previous essay framing the decade in Artlink 36:4, “The new capitalist realism: Science fiction in art of the 2010s”.

Changing register, Wes Hill in “Stuart Ringholt: Time pressures” takes on this artist’s eccentric headspace as a study of how Ringholt uses the measure of time to try to “abbreviate the world—to time, to bare skin, to the social sphere, to primal psyches” as a form of self-help or therapy that also manifests the cultural logic of our times. Ringholt’s various large-scale clock works, including Nuclear Clock, exhibited in the Aichi Triennale in 2019, and an earlier work featured in MCA Collection: Today Tomorrow Yesterday, recalibrate the settings to move us on from the non-stop 24-hour time of global markets altogether.

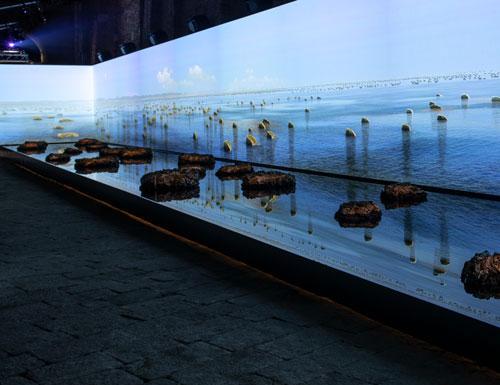

Deep time—geological time—as an evolutionary experience, inspired by the inundated thrombolites found in an ephemeral lake, is presented in a feature on the Living Rocks: A Fragment of the Universe by James Darling and Lesley Forwood, working with Jumpgate VR, recently presented as a collateral event in the 2019 Venice Biennale. And, in a similarly active interface with the living face of rocks and earth, Mandy Treagus writes on Lee Harrop’s project Still Lives, working with samples from the Northern Territory Core Library, and Abbra Kotlarczyk maps timed encounters with the landscape terrain in a collaborative text, “Geological pit stops: Kate Hill and Isadora Vaughan”, in reference to the outcome of a residency at Watch This Space in Alice Springs.

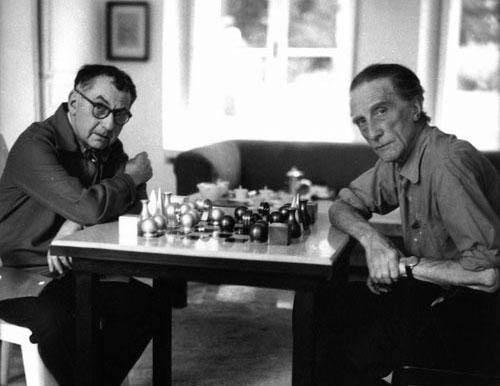

Two concluding essays revisit the case for restoring a more active agency to art history that is located in latitudinal thinking through access to archives and collections. “Duchamp and Australia: In opposition” by Rex Butler and ADS Donaldson is a delayed response to The Essential Duchamp at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the artist’s alternative career as a chess player. John Mateer’s “The Brazilian moment: A picture gallery in transformation” revisits earlier models of exhibition display at the Museum of Art São Paulo to empower the viewer’s encounter with art as self-directed, even self-empowering.

As Wes Hill quoting Bruno Latour points out, “Time does not pass. Times are what are at stake between forces … There are as many directions as there are agents capable of making their positions irreversible.”