.jpg)

There was no ceremony for the last day of Sakahàn the first quinquennial exhibition of International Indigenous Art, but the sky went dark grey, a thunderstorm cracked it open and heavy rain bucketed down in the last half hour. This seemed entirely appropriate as connection to nature, and therefore weather, is a recurring element of indigeneity.

And what are the defining elements of indigeneity? Frequently it is indefinable, fluid, or withheld, at other times it is definitely an overriding connection to the earth, the voices of animals and other non-human forms of life.

Certainly Indigenous art is not a monolith of any kind and perhaps a refusal to be defined is a defining characteristic of it. One of the curators of Sakahàn Greg Hill wrote an Afterword in the catalogue in which he imagines he is writing in 2038 after six Sakahàns have been held. He writes: "Strategically indigeneity is flexible enough to serve as required. As a concept or construct its defining characteristic is its mutability. Indigeneity as a concept, a container, has to be plastic enough to expand in any direction while maintaining its integrity. Indigenous artists understand this."

Another curator Christine Lalonde quotes artist and theorist David Garneau from a paper he delivered at the 2011 Essentially Indigenous? symposium at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York. “We read, write, and critique ourselves into contemporaneity. This is self-determination. Figuring out what is or who are essentially Indigenous is no longer a Settler issue, it is an Indigenous problem.” Yet another essay by Columbian Catalina Lozano speaks of “the epistemic trap of Eurocentrism” next to an image of a 2012 work by Eduardo Abaroa titled Destruction of the Museum of Anthropology.

In this exhibition with more than 150 works of relatively recent art by over 80 artists from 16 countries, by indigenous people based in India, South America, Greenland, Denmark, Taiwan, New Zealand, USA, Australia, Japan, Norway, Finland, Mexico and Canada, there is heaps of difference. So the agenda of Sakahàn, which means in Algonkian (the language of the First Peoples of the land on which Ottawa is built) “to light a fire”, is complex and detailed.

The recurring topics of the art on show, as suggested in Lalonde's catalogue essay, are “self-representation; histories and encounters; the value of the handmade; transmigration between the spiritual, the uncanny and the everyday; homelands and exile; and personal expressions of the impact of physical violence and societal trauma.”

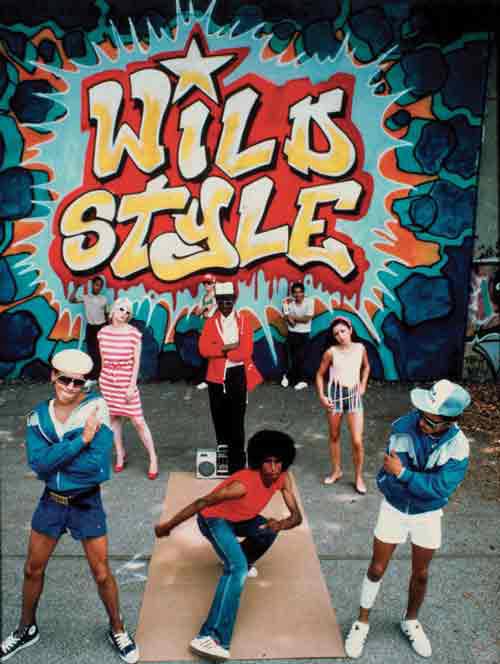

Sakahàn was located in several sites (in the satellite Indigenous and Urban at the Canadian Museum of Civilisation there was local Canadian material - including djs, graffiti, photographs, and dance; and at the Ottawa Art Gallery a four person exhibition called In the Flesh about relationships between people and animals which included Buffalo Bone China, a work by Dana Claxton using mesmerising archival footage of buffalo running) but the International Art was in the National Gallery of Canada. It has a large glass tower at one end and a monstrously large Louise Bourgeois Maman 1999 standing guard at the entrance at the other end. Sakahàn asserted itself immediately from outside the Gallery by an immense three dimensional photographic Iluliaq (Iceberg), the work of Inuk Silis, which was built over the crystalline glass tower which burst through it as if both were half-finished or in conflict.

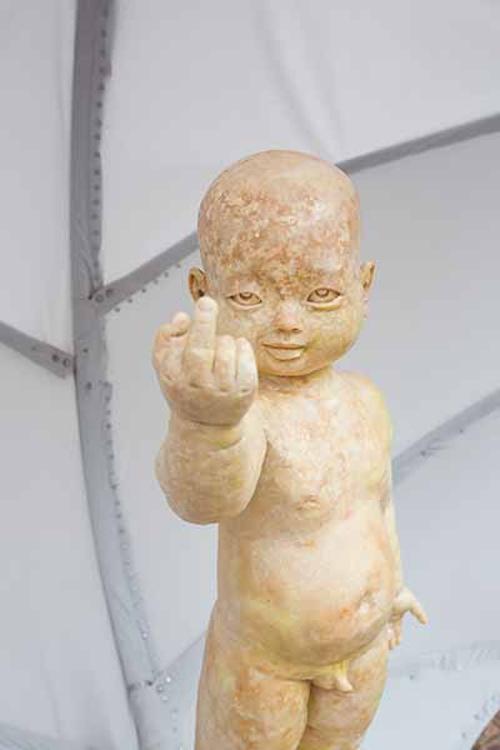

The entry to the exhibition was up a long ramp above which hung Earth and Sky a banner decorated with airy symbols made by Shuvinal Ashoona and John Noestheden. On reaching the top of the ramp you entered a round room through swooshing automatic doors. In the centre of this small self-contained space was dramatically placed Michael Parekowhai’s My Sister, my Self – a black shiny fibreglass seal balancing on its nose a handmade replica of Duchamp’s Roue de bicyclette from 1913. The playfulness of this gesture, making a circus plaything from one of the iconic works of conventional European art history, was strong and lighthearted. It suggested the opening of a conversation with Eurocentric art, perhaps even a confrontation with its conventions and habits.

This idea was borne out in the next gallery which contained impressive works by Danie Mellor (blue and white chinoiserie-style drawings of rainforests and Aboriginal people with traditional shields, and above on the ceiling - a skull and a blue moon), Jonathan Jones (many lightbulbs hanging from white cords) and Kent Monkman (Boudoir de Berdashe, a teepee within which a highly camp video about race relations and the Western frontier played). And the soundtrack of Vernon Ah Kee’s cantchant could be heard from nearby. So Australian art was in the foreground, and Brenda Croft was one of eight international curatorial advisors to the show – although there was no essay in the catalogue from an Australian. Altogether there were five Australians as Warwick Thornton’s Nana video and Richard Bell’s video Scratch an Aussie and Life on a Mission painting were also included.

After these first few rooms things got very diverse and less familiar. The quantity of work and its variety made it pretty well impossible to follow any train of thought or theme – it was more a matter of does it talk to me and why? And maybe this entering into a feeling place and not a thinking place was appropriate.

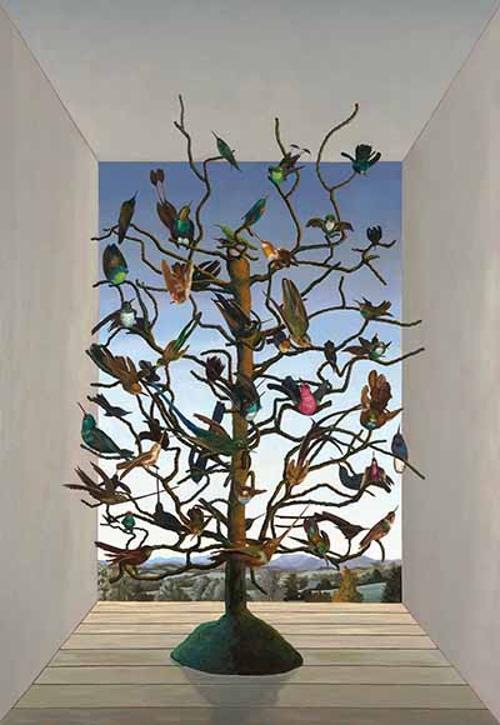

I lingered over the work of Pia Arke which uses maps, photographs and substances like coffee, sugar, rice, flour and rolled oats as well her video Arctic Hysteria; and enjoyed the drawings of Itee Pootoogook of daily life in Cape Dorset. I experienced the disorientation, immersive and dreamlike, of the video installation of Brett Graham and Rachel Rakena’s Aniwaniwa about cultural loss and forced migration in Aotearoa New Zealand. Abel Rodriguez’s detailed six drawings of Seasonal Changes in the Amazon Forest were totally absorbing while Lucinations, the projection of Doug Smarch’s video which recreates the prophetic dream of a medicine man onto a screen of white feathers, was hallucinogenic. Then there was Steven Yazzie’s jittery drawings of Monument Valley made while riding through it in a buggy. And in a gallery flanked by Sol Le Witt wall drawings was Encore tranquillité [Calm Again] Jimmie Durham’s fibreglass boulder crushing a small aeroplane.

Was the work International or was the exhibition International? How many people saw it? Will its next manifestation be elsewhere? Who is it talking to? Regrettably the substantial and informative wall panels which illuminated the artworks are not in the catalogue.

As much as there were recurring references to age-old traditions there was definitely a sense of a beginning in Sakahàn. Even a sense of always beginning and of ongoing exploration, of completely unpredictable outcomes, of multiple directions, of valuable materials and territories, and important messages and observations, to hopefully continually enrich and confront contemporary art rather than conform to its paradigms. Indigeneity definitely increases the vocabulary of all humanity and, just maybe, being indigenous means being human.