.jpg)

The so-called third wave of craft seems no myth given the current momentum awarded to applied artisan practices. Void of studio romanticism and earlier therapeutic claims the collaborative potentials of craft are coming forth – fostering social relations and glocal propensities also. For the third time in the space of a year QCA's WEBB gallery is host to an exhibition consisting exclusively of jewellery. This time, however, the focus is not recent graduates from the institution’s Jewellery & Small Objects department or emerging artists from universities abroad. Transplantation presents narrative jewellery from "12 contemporary jewellery artists", the thematic concept doubling as title. Consistent with notions of migration and colonisation participating artists are based either in the UK or Australia – each exploring a sense of place and identity provoked by their own experiences of cultural, familial and artistic transplantation.

The term “Narrative” used to describe content and not context has only been associated with jewellery since the 20th century. The formulation of an overtly personal (albeit contained) narrative relies on a semiotic reading of compilated visual imagery and materials in relation to the self. This is a kind of self-centred yet intimately existential method of constructing meaning through an often-unambitious employment of collage strategies. Such personal orientation sometimes overlooks greater possibilities for the practice, signs of which are manifest in the presentation of these works.

Text assumes an explanatory function; a coinciding wall didactic for each vitrine provides a biographical background and information on processes. Further writings nestle uncomfortably in the vitrines, endowing academia a value equal to that of the work.

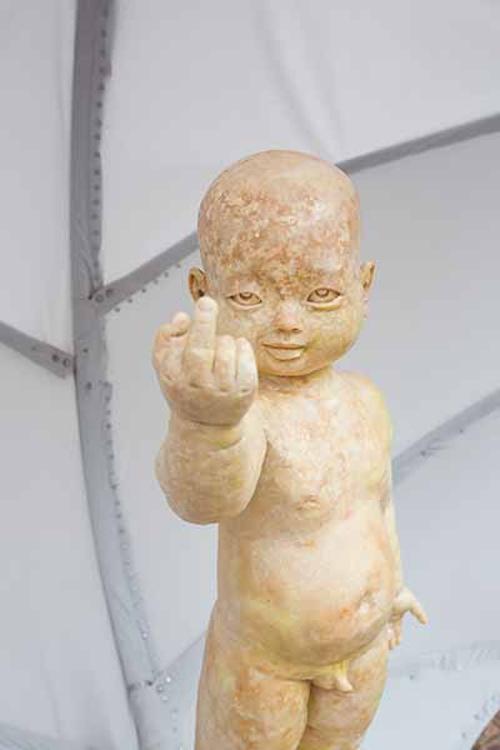

Perhaps the works less concerned with personal histories are better situated for social commentary. Nicholas Bastin hybridises referential objects as points of departure for fictitious storytelling. Hand-carving, moulding and casting polyurethane allows Bastin to utilise highly saturated colour with toy-like patina. Not dissimilar to action figures; sharing in a similar vein the corporeal manifestations of imagined places.

Sheridan Kennedy is interested also in conjuring otherworldly mutations. Drawing parallels between biological adaptation and jewellery’s role as art object. Insects composed of gold and coral coexist with silver crustacean hybrids thus re-assessing our ideas about jewellery as passive objects while simultaneously investigating interactions with place, notions of habitat and objectivity.

To theoretically position this narrative jewellery between self-portrait-painting and particular kinds of sculpture may help us understand how it operates as an object in space. It exists three dimensionally yet it has certain pictorial planes that forbid us to exist 'with’ it in time but rather require contemplation in the same key as a painting. If ‘sculpture is what the history of sculpture is the history of’ then jewellery’s ability to be worn may well be a way out of this medium qua medium paradigm. The preface to the exhibition by Norman Cherry alludes to jewellery’s potential as “eminently portable, wearable artform”. This is a very true potential yet contradictions arise when this is spelled out to us on the wall of a gallery. To admit the relevance of gazing through the glass of a vitrine is to reject the possibility of realisation through use. Undoubtedly though, wear-and-tear would most likely decrease the jewellery’s value as an art-object – problematic to say the least.

Perhaps a lack of ambivalence about presentation is what lets this exhibition slip in stature – disappointingly denying justice to some beautifully crafted, thought-provoking works. Transplantation seems to say: “here I am", instead of “should I be here?” – a question asked with integrity.