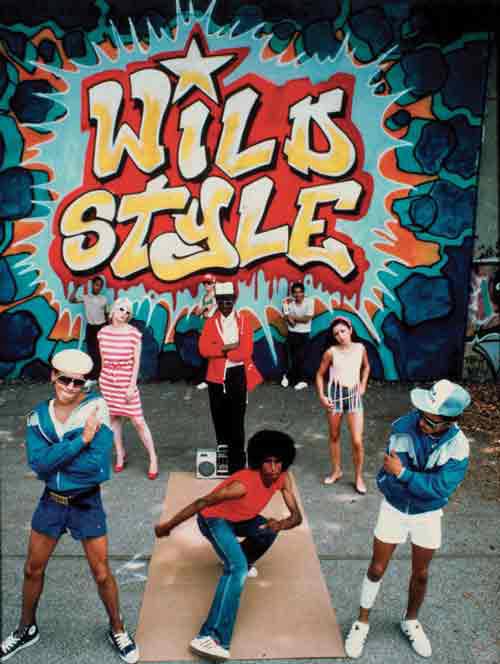

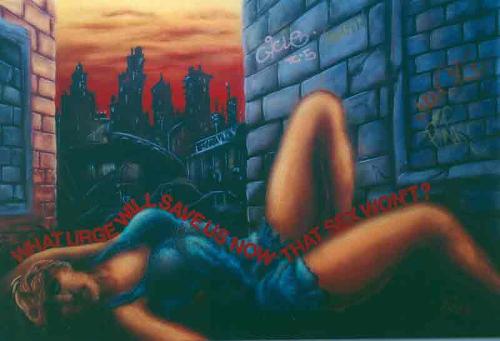

Wildstyle women: female hip hop graffiti

Hip hop graffiti is considered a predominantly male subculture, but girls and women have been consistently involved since it first emerged. While contemporary media accounts often overlook this fact, the first report of the subculture in the mainstream media, Richard Goldstein's 1971 New York Times article ‘“Taki 183” Spawns Pen Pals’, did mention Barbara 62, one of the first female writers. Barbara 62 was prolific on the streets and subways along with other female writers of the early 1970s, such as Eva 62, Michelle 62, Stoney, Cowboy, Grape, Charmaine, Kivu, Poonie 1 and Siku 1.