.jpg)

In terms of the year of its timing in 2013, the Biennale of Singapore's title - If the World Changed, seems more like a taunt than an invitation. The extraordinary extent to which the world has changed – at times in ways that are irretrievably lost – provides the subject matter for so much of the work included.

There was a sense of rhythmic gravity to this show – a meter that sounded out at various sites throughout the exhibition in works that marked out changes that have passed, and hinted at how these reverberate into changes that might come. At the Institute of Contemporary Arts the exhibition Lost to the Future curated by Charles Merewether featured the work of artists from Kazakhstan, Krygystan and Uzbekistan. Throughout the works included, dust from the Soviet Union’s collapse seemed suspended like a pall. This exhibition was a fitting entry point to the scattered inclusions of this Biennale, serving as a reminder how quickly any dreams of change can sour. Nowhere is this more poignant than in the work of Kazakhstan artist Almagul Menlibayeva. Her most recent multi-screen work titled Kurchatov 22 (2012) at times seems on the edge of slipping into social documentary. Images of lives and landscapes laid bare as the result of nuclear testing provided poignant evidence of the real costs of any dreams that enforced change will bring betterment to all. However Menlibayeva is ultimately successful in raising the implications of her work to a zone that is neither propaganda nor morality play – rather, her imagery celebrates the refusal of passion to be buried along with the broken buildings, the failed experiments, the rusted equipment and the residual fear.

In Peace Can Be Realised Even Without Order, created by the Tokyo-based teamLab (est 2001), fifty-six individually programed characters, each delineated as a simple line drawing cast in light on its own Perspex screen, stand poised and slowly breathing, waiting for a call to begin. Shimmering and incandescent, the light-sensitive figures respond to the presence of the viewer in an effect that verges on the transcendental. Adorned in traditional Japanese costumes, this ghostly orchestra majestically and mutely mime the dance-steps of an ancient choreography. Audience members move through this labyrinth of apparitions as if we are the ghosts – as if the spirit world of the past has an order and sequencing all of its own – one that calls up the most ancient of rhythms and the purest, most simple of gestures to remind us of the inter-connectedness of times, traditions and existence. The slow-paced rhythm of the work, the hypnotic quality of reflected and refracted light and the astonishing beauty of the score come together in a work with a somnambulistic power that lasts well beyond the audience experience.

The AX(is) Art Project (est Baguio, Philippines 2012) is an interactive collaboration of a very different order – one whose guiding principle of "Art Access for All" necessitated an adaptation of technology production at the opposite end of the ladder to that of the cutting-edge teamLab. However the makeshift, dog-eared and endearingly scruffy nature of the installation was no less affective in reminding audiences of the potency of history, Indigenous knowledge and the capacity of artists and art to act as conduits between the past and future. The fact that the work of two of the artists who are no longer with us – Santiago Bose and Roberto Villanueva – was included carried through the theme of the Biennale in a deeply personal way for those of us with enough lifespan to remember their legacy in contemporary art in the Asia-Pacific region. People pass. Times pass. The world changes. Art lives on to document this. It marks the changes as we look back. And at times its forms can offer prescience about what might come.

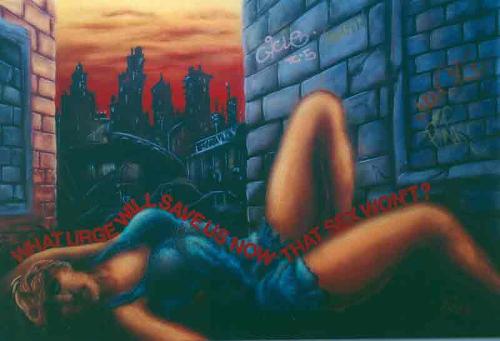

The darker side of what the future promises was the subject of the split screen video installation by Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho (Korea) in which two unfolding stories about the effects of a post-apocalyptic world on the responses of two very different protagonists are simultaneously narrated. Within the pristine perfection of a futuristic white lab a scientist – a young woman – is faced with the task of categorising and ordering vestiges of life gleaned from the world beyond the lab. The other screen features the richly cramped disorderliness of an artist’s interior. He too collects and collates, albeit with a process that is far more haphazard and organic. The work hints at elusive connections and synergies as the tasks of collecting, analysing, assessing and recomposing that lie at the core of art practice are laid side by side with those of a futuristic scientific taxonomic process. Between these loose and connected narratives the Biennale’s theme hovers and inflects. There is a saturating sadness to the work – one where the robust “laugh in the teeth of futility” that inflected so much of last century’s future-fear seems to have collapsed into a poetic acceptance of the inevitable.

If the stated intention of the curatorial theme of the fourth Singapore Biennale is in part to reveal “the long roots of civilisation, multiple foreign influences, and distinct and overlapping religious and spiritual bearings of the region’s histories” there is also a sense of the interconnectedness between the regions beyond to suggest how the planet as a whole both mourns and celebrates the way the world’s changes have been responded to by art and artists. Featuring the works of 82 artists and collectives from the Southeast Asian region (in which Australia is not included), the curatorial process adopted a regionally-diverse 27 member curatorial team. A lasting impression is of a show that is far less celebratory of change than the corporate skyline of Singapore might suggest. Instead, like the recent work of so many artists of this region, the traditions of the past are often re-harnessed to reflect their radical potential to extend the potency of creative re-translations back into the past as well as into the future.