Following directions from a young ecologist, Lesley Forwood and I waded through a shallow, ephemeral swamp in the south-east of South Australia and found thrombolites, rock‑like microbial accretions, which, along with layered microbial stromatolites and over a period of three billion years, became the source of oxygen for our planet. It was a rare, exhilarating, other‑worldly experience.

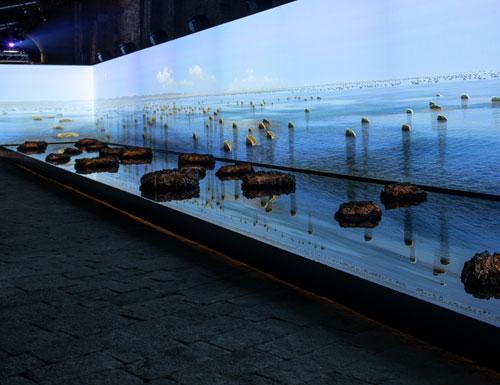

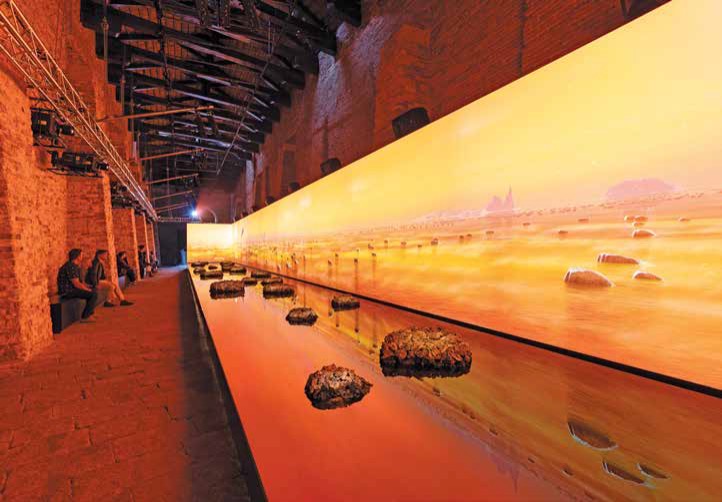

The inspiration of that visit came to fruition as Living Rocks: A Fragment of the Universe, a far‑reaching collaborative installation in a fifteenth‑century stone warehouse, the Magazzini del Sale in Venice. A Collateral Event of the 58th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2019, it attracted 70,000 visitors over the duration of the exhibition.

There are locations where evolution is writ large, enabling us to revel in nature’s unceasing, endemic dynamism and change. The clarity of geological time is a feature of the Australian continent that sets it apart from much of the rest of the world, highlighting this audacity and availability of environmental history and its massive, unrealised potential for artists. It is a realm where science and the imagination co‑habit.

The foundations of Living Rocks were built on scientific insight. And for this, we had the benefit of scientific advisors, Robert Burne, Emeritus Professor of Earth and Environmental Science, ANU, and Malcolm Walter AM, FAA, Emeritus Professor of Astrobiology, School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences, UNSW.

Immediately on meeting Bob Burne, it was obvious that he was an enthusiast about all thing microbial. He exuded a passion for microbes. They were in his DNA, his genes, his bloodstream. His language about microbialities tested concept and imagination. They were the “earth’s default ecosystem.” Microbes could build structural foundations as large as the Great Barrier Reef. They had survived the great extinction events of the planet. His words, which I shall return to, laid bare an awareness of evolutionary time which tested our bounds of knowledge and imagination.

He set us on a trail to the edge of conception. What was our planet three billion years ago and how could a connection be established between now and then?

Malcom Walter offered us the one image he knew of that era from the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. It had the features of an inaccurate cartoon. Malcolm set us on the track of getting the visuals right: pink skies, a steaming slurry of oceans, no land mass, volcanic outcrops and archipelagos, different cloud banks, a closer moon, a more distant sun, clearer stars, asteroids. He worked with us and our major collaborators, JumpgateVR, to enunciate a vision of our planet that no one had ever seen.

Integral to the twenty‑five years of making installation sculpture is our unspoken conviction that content was always at hand and that there was no cultural cringe, not between continents, countries, cities or regions. The crux of the matter in this one life with no dress rehearsal was to be open-eyed, to do what you meant, to move into unoccupied space, to connect, to reveal, to shift the axis.

The density of evolutionary experience within a two or three hours drive from our farm in the south-east of Australia creates that enlarged perspective. Just beyond the extraordinary exit of the Murray River to the Great Southern Ocean is the rock ridge that encases the wonderful fertility of McLaren Vale. The rock is two billion years old—as old as the Kimberley—and at the other end are the thrombolites, growing at one cubic millimetre in one hundred years. It is “a contemporary ecosystem,” to use Bob Burne’s words, that is millions of years old. The continuing creation of the Younghusband Peninsular—so recent, at only 7,500 to 10,000 years old—is not even the blink of an eye in evolutionary time: and there it is, evidence spanning and enacting two billion years of life at our doorstep.

di Venezia, 2019. Photo: Francesco Allegretto Fotografo. Courtesy the artists and Hugo Michell Gallery

Such an acknowledgement creates perspective. It humbles. It exposes hubris. It speaks of the vanity of humans. It insists that relationship to country takes shape and form within the oceanic orchestral range of environmental time.

The science of Living Rocks is apt. It is of our time. There were three billion years of planet Earth when the only living organisms were microbes. Now, with our ability to investigate more‑and‑more minuscule lifeforms, microbes are fashionable—those in our gut and those in the soil most obviously. Microbialities offer a clue to health, to food, to productivity and a notably optimistic field of study which can make us live better, longer and more fulfilled lives.

Microbes built our world. They were the first and largest source of our atmosphere. They have survived the great extinction events of environmental history. We depend on microbes. But, in the end, microbes can live without us.

Living Rocks found a way to say this while extolling and celebrating the poetry of our planet, our beautiful Earth that we have misunderstood for so long as if its resources were infinite and without boundaries.

Marshall McLuhan’s revolutionary phrase “the global village” coincided with the oil crisis of the 1960s and 1970s, the first image of the blue Earth from space: they were markers that entailed the imperative of an enforced adjustment to endless consumption. All change is incremental. Nature is implacable.

To return to Professor Bob Burne and microbes as “the Earth’s default ecosystem.” He also challenges our notion that the Anthropocene Age is a new epoch; rather, he asserts, it is the beginning of a new extinction. He gave us the notion that headlines our artist statement that accompanied Living Rocks in Venice.

A memory of our origin and a prophesy of our future:

The price of entry is departure.

I don’t mean now, not this instant, but in the time‑scale of the planet, it’s inevitable.

Fragility. Recognising fragility is the human imperative the world over.

We arrive, we enter.

The seed that is sown carries departure, the exit that was born with beginning.

Can it be any other way?