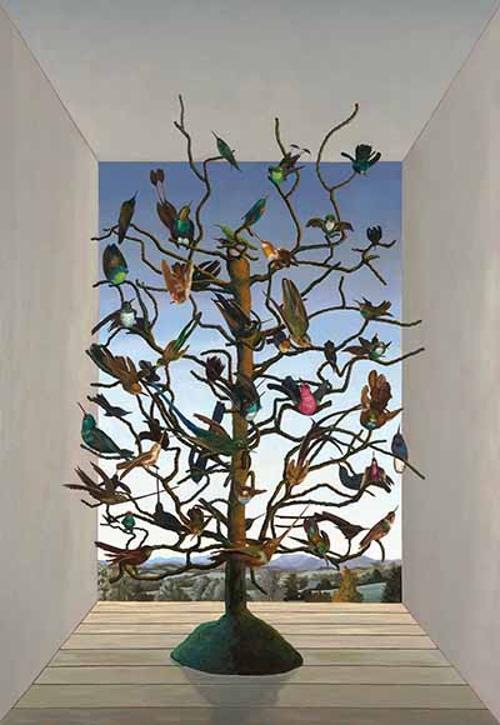

Portraiture would seem, ipso facto, to be the most constrained area of contemporary practice. In subject matter, it is tethered to depiction of the very specific reality of an individual or group of individuals, and in formal realisation it is bound to variations of figurative representation. This book of photographic, painted and sculptural portraits by fifty international artists shows how little that constraint matters when it comes to making powerful and imaginative art. 21st Century Portraits catalogues an extraordinarily diverse array of creative strategies, ranging across extremes from the glossy high-production values of Thomas Struth's exquisitely lit double portrait, Queen Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh, Windsor Castle, 2011, to Marc Quinn’s infamous self-portrait head, Self, 2006, cast in his own blood. Then there is Tim Noble’s and Sue Webster’s silhouette self-portrait, created by projecting light onto intricately constructed detritus and mummified animals (AGSA recently acquired a similar Noble/ Webster self-portrait), or, Tomoaki Suzuki’s hyper-realistic miniature sculptures carved in lime wood and painted, depicting local denizens of his East London neighbourhood.

The book is a handsome, lavishly illustrated publication, with a strong selection of artists, most of whom are well-known or even famous, though not necessarily for portraiture. In an attempt to corral so much diversity, the book is divided into seven sub-groups: observational portraits, self-portraits, commissioned and celebrity portraits, social portraits, geopolitics and national identity, the body and finally, reinvented portraits. Each artist has been given a generous pictorial spread over four pages, with supporting text by Australian Jo Higgins, including abbreviated resumés and extended pictorial captions. This text proved essential in cases where the artists and/or their sitters were unfamiliar, but also added crucial information to illuminate the more familiar images.

Included in the roll-call are obvious choices of artists who habitually make portraits, including Lucian Freud, Annie Leibovitz, Sam Taylor-Wood, Jenny Saville, Gillian Wearing, and Michael Landy; and some less predictable inclusions of artists working in areas of social and political identity, including Grayson Perry, Marlene Dumas, Antony Gormley and Christian Boltanski. Australian artists who made the cut are Tracey Moffatt, Ben Quilty and Daniel Boyd.

Amidst this smorgasbord of approaches to portraiture, the images that left a lingering impact were in some respects quite conventional. In his prize-winning photograph, Huntress with Buck, South Africa, 2010, David Chancellor depicts a 14-year old American tourist astride her horse with her trophy, a dead wildebeest, draped across her lap. The image has an understated, chilling beauty, resonant with complex undertones around game-hunting, tourism and gender. London-based German fashion photographer Juergen Teller has created a compelling image of British designer Dame Vivienne Westwood. Reclining nude on a floral settee in an Odalisque pose, Westwood displays her 70-year old body in all its unadorned vulnerability and astonishing whiteness. As a counterpoint to this nakedness, her dyed orange hair is coiffed, her face carefully made-up, with a slash of red lipstick, and her surprisingly youthful hands are manicured. Rather than averting her gaze, she stares calmly at the camera, with a slight smile of amusement, possibly at the incongruity of being stripped bare of the clothes which normally define her identity.

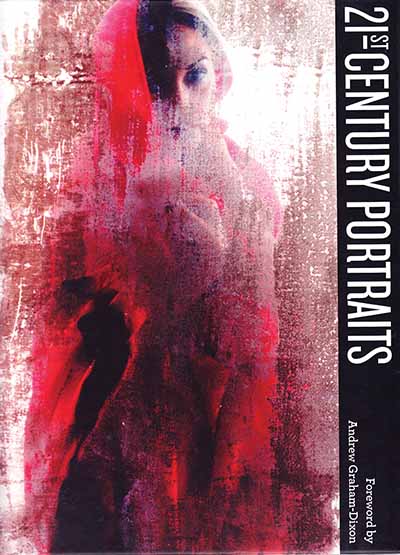

In contrast to the strength of the artist pages, the introductory essays lack incisive insights on portraiture as a contemporary medium. There is a foreword by Andrew Graham-Dixon, in which he states that portraiture today has witnessed "an invigoratingly wide redefinition" of previous limits. In a more extended introduction, joint authors Sarah Howgate and Sandy Nairne, respectively Curator and Director of the National Portrait Gallery, London, grapple with the role of portraiture in probing personal and cultural identity in the context of social media saturated with images of selfies, friends and celebrities. One final niggle, the book is hard to navigate, as artists are not in alphabetical order, or paginated in the Contents, requiring reference to the index to find particular artists. The publication appears to be the work of a large cast with no strong editorial direction (reflected in the lack of a cover/title page credit for an author/editor). These deficiencies detract from what is in many respects an important, but not definitive, work on contemporary portraiture.