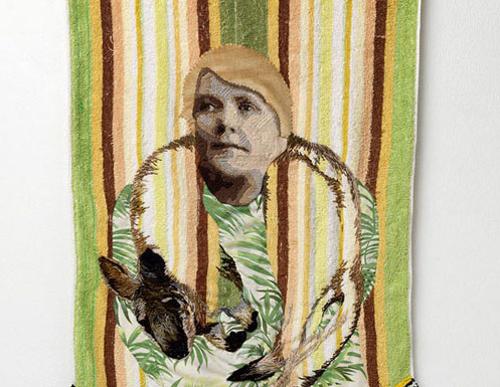

Thronging Bluff Face: Jemima Wyman's many masks

If every discrete uprising is a repetition, a citation, then what happens has been happening for some time, is happening now again, a memory embodied anew, in events episodic, cumulative, and partially unforeseeable.