Search

You searched for contributors, issues and articles tagged with Emotion ...

Contributors

Issues

Articles

When I was eleven, I assumed the role of keeper of the family archives: with both parents working and me the younger sibling, I probably had the most time on my hands. But I also felt a strong compulsion to guard mementos from family holidays and special occasions, including images. With the solid moral universe of a child that age, I wanted to capture the “true” version of events, preferring candid to posed photographs. I was renowned for gonzoing formal photo opps by pulling a face or kicking out an inopportune leg. You can imagine my outrage when I discovered my carefully compiled albums had been raided. Every “unflattering” photo of my mother had been removed, leaving virtually no trace of her. When confronted, my mother was unrepentant and refused to return the photos, claiming she had destroyed them as was her right. I was so angry that she would presume to interfere in our collective family record and incensed at what I saw as her hypocrisy and inability to face “the truth”—that she was ageing. Looking back, I have a great deal more compassion for my mother’s response. But this poignant memory makes me reflect: how many other family archives suffered a similar fate (let alone in the digital era)? Was internalised shame at work? And, what counter‑truth was my mother asserting?

I submit to my stocktake shifts, become their restless subject, sighting, countersigning, pitting numbers and images against objects. “Randomised”, my colleague tells me, from an appropriate social distance. A performance of witnessing without expectation (at least on my part) which is why his appearance was closer to a manifestation.

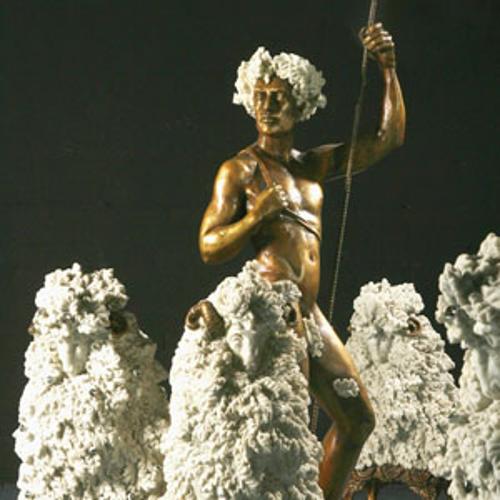

Stephen Benwell’s little statue. With a rush of feeling, he wholly punctured my procedural glumness. His tender realness, eyes fluttering upward to a neighbouring stoneware pot, he chastises the unimaginatively robust seventies ceramic for what it might have been. His twenty-something centimetres of tragicomic beauty resolute against the silent grey of our diligence. Not just present but a presence of self-elegiac composure. A resistance.

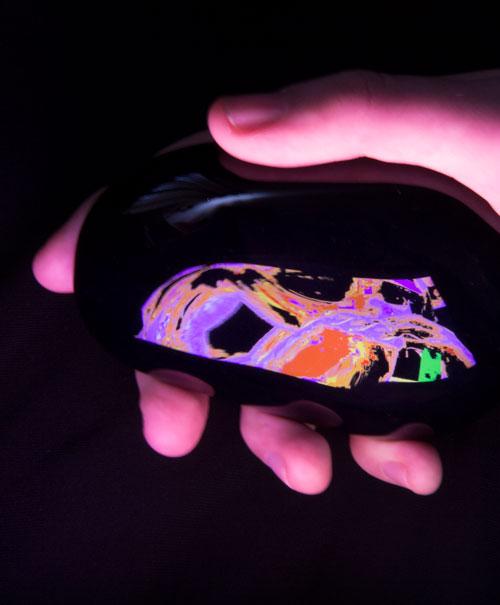

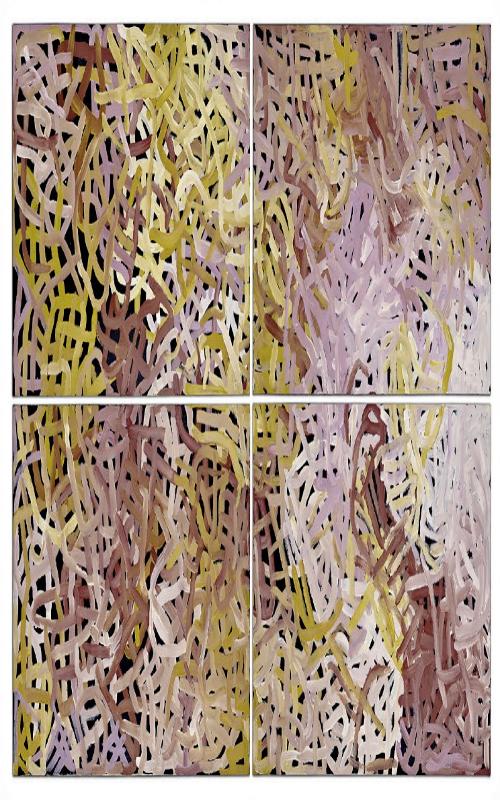

We do not see like a camera. A camera registers everything reflecting light into its lens, but human perception is selective. It is an economy of resources that has evolved over millions of years so that now, neuroscientists tell us, only about twenty per cent of what we perceive visually from moment to moment is actually passing through our eyes. The rest is constructed from memory and expectation. Our experience of the world is a product of interactions between abstract top-down visual memory templates and bottom-up sensory ones. Since the former is subjective, we rarely perceive those things that we fail to consider. Sometimes, to understand the bigger picture, we must squint our eyes and soften our focus; to concentrate less on the things we seek and become conscious of the interplay in how things blend together.

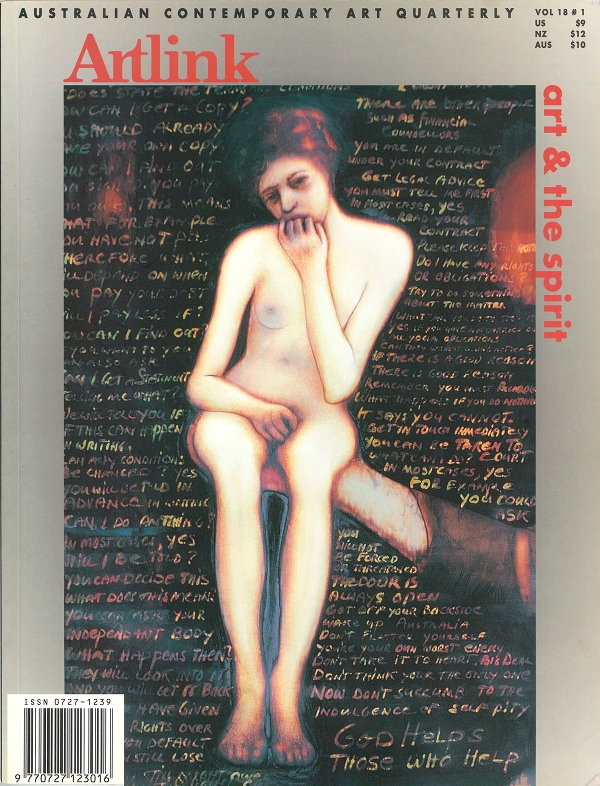

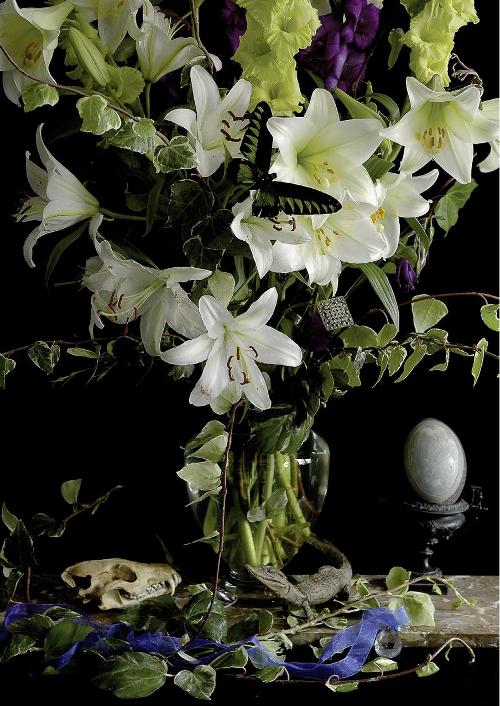

I have lifted the title for this essay from Narratives of Dis‑ease (1990), a series of works by the late British photographer Jo Spence. The series was made following the artist’s partial mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. Closely‑cropped around her body, the photographs show Spence partially nude, using props and performing emotive gestures, compositions and sight gags that were suggestive of the sub‑titles she ascribed to each individual image: Expunged, Exiled, Included, Excised and Expected.

Why I do them is to be around people that don’t have any fear.

I want to see what it’s like to be around people who are really happy.

Stuart Ringholt’s anti‑anxiety Anger Workshops and stress‑healing Naturist Tours step outside the usual model of clinical healing practices. They revisit the potential of being happy by living in the moment as a form of liberation and group therapy that is creatively driven. The first of the Naturist Tours began as part of a show on art and therapy named Let The Healing Begin (2011) at the IMA in Brisbane. Curator Robert Leonard commented that many regular gallery goers politely declined the invitation to take part, and although he was low key in his advertisement of this aspect of the show, it created a tremendous amount of community and media interest. Fast forward to the subsequent tours through the Wim Delvoye Retrospective at MONA (2011), and James Turrell: A Retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia, and Ringholt’s practice has all but surrendered to the demand, with an accelerated following.

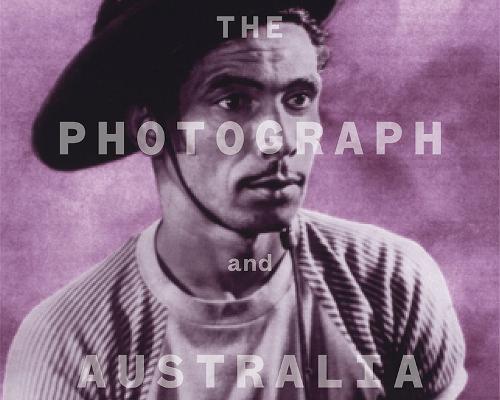

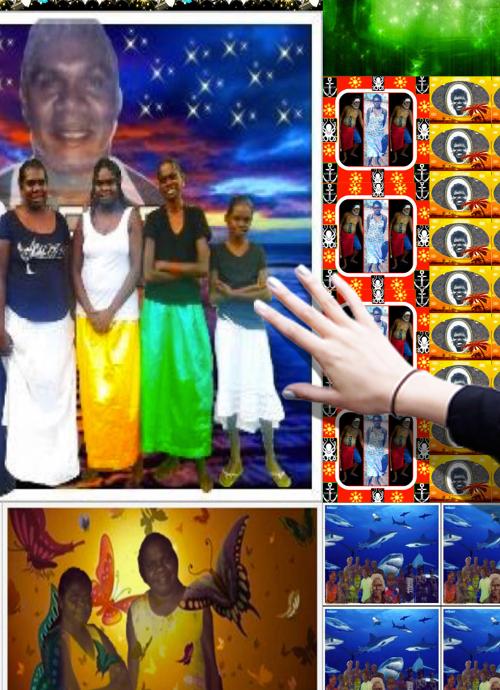

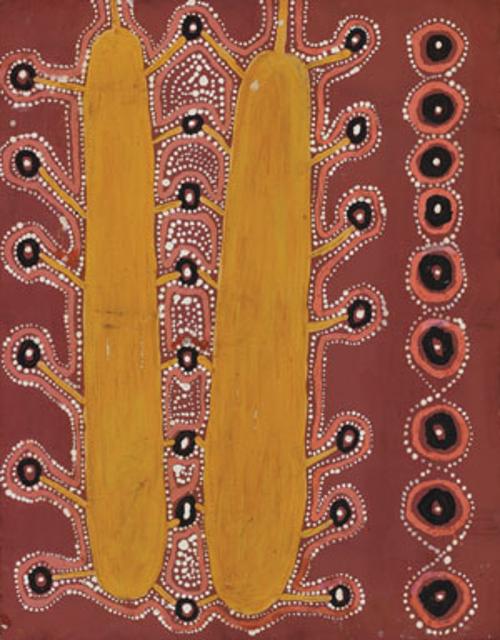

The affective power of a photograph is perhaps never more potent than when the subject is a lost loved one, as Roland Barthes famously discussed on contemplating a portrait of his dead mother. This appreciation of the role of photography is harnessed in a new digital artwork by the Miyarrka Media collective which uses family photographs, including many images of deceased family members, as the basis for an interactive digital artwork about the importance of family and feeling in an age of interconnection.

I am autistic. I perceive and experience the world through sensory and cognitive pathways unique to autism. Neuroscience documents this as “sensory atypicality” and “detail‑focused perception.” In terms of lived‑experience, this means the senses react in ways different from the norm, and the mind attends to minutiae that most others dismiss or miss altogether. Autistic sensory‑cognitive idiosyncrasy unpacks in myriad ways, varying from person to person and in modulations that range from intense attraction to extreme aversion.

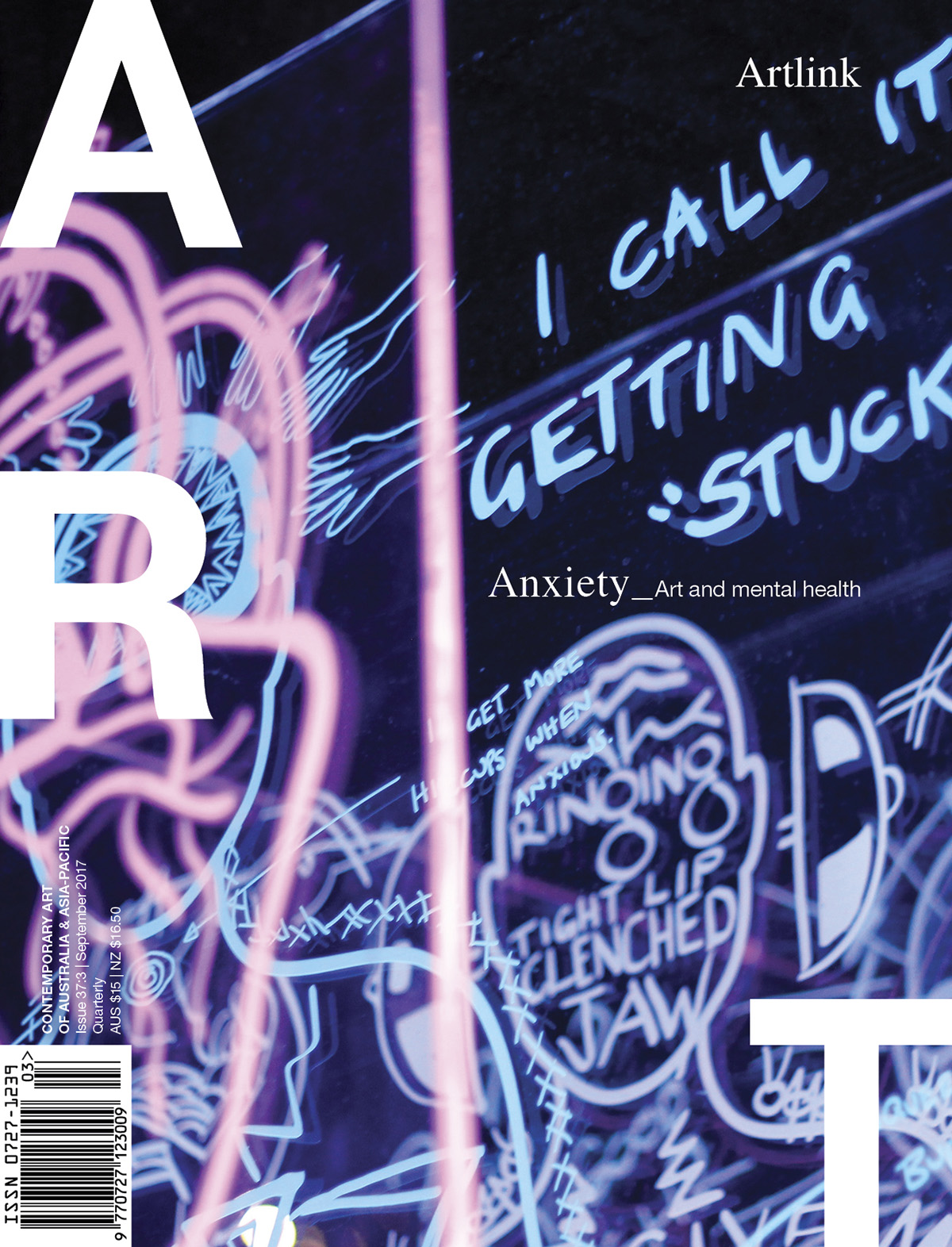

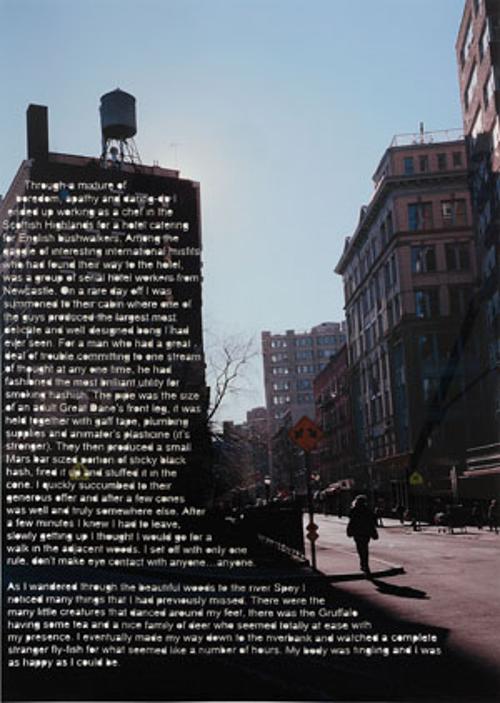

I am in France. I have been working towards a presentation related to my research on panic at the Sorbonne, at a conference called Lire Pour Faire. I am anxious, sick with it, actually. My paper is dry and I need wet. The wet of tears, the wet of biochemicals pumping through blood, the wet of fear-piss. I want to vomit and I want to scream. Instead I sit in my room and hyperventilate. I find my friend and disclose my fears to her. I am in a state. She convinces me to do a practice presentation for a group of people who will be kind and supportive. I perform my disquiet and my insecurity and it is painful, and the pain is felt, and there is silence. There is a sitting back, a sinking down, a closing of laptop lids. There is quiet. Sometime after the quiet somebody tells a story and there is talk, feedback, questioning, exchange, confusion. This is where the research happens. Elsewhere, and otherwise, and afterwards.

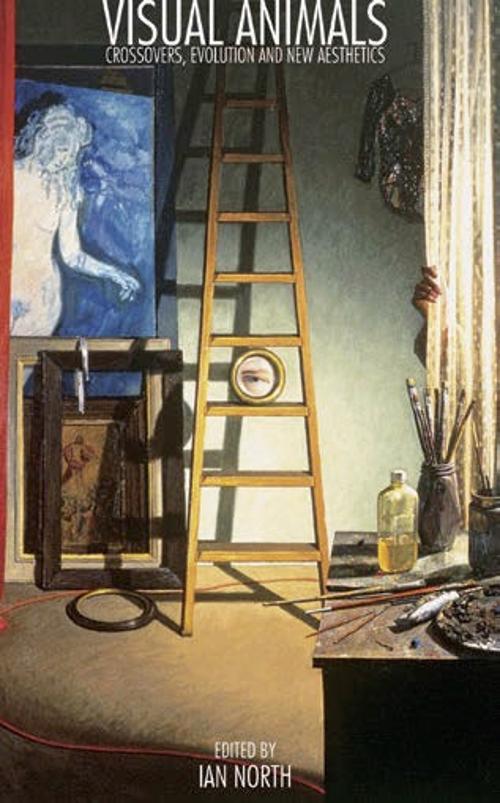

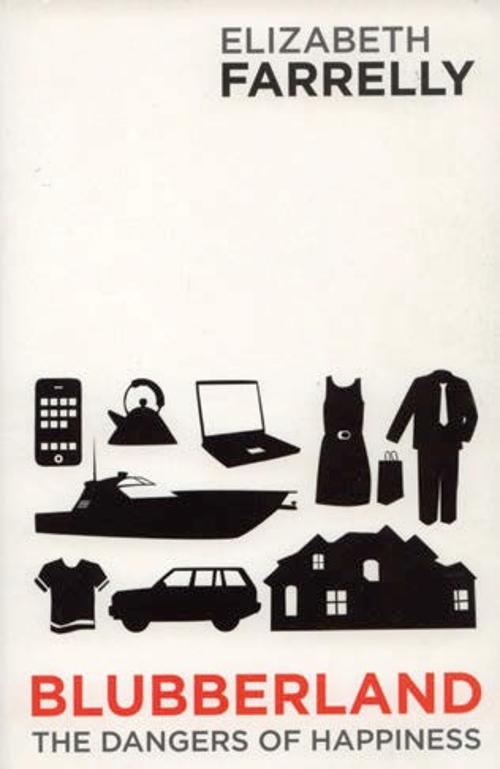

New York and London, Routledge 2007, RRP US$135

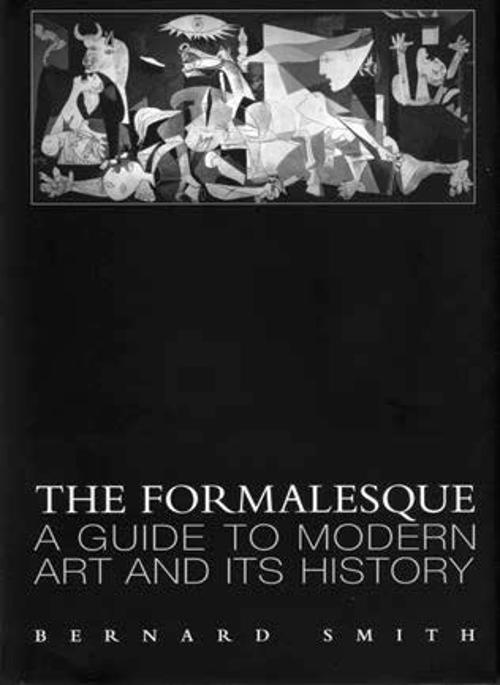

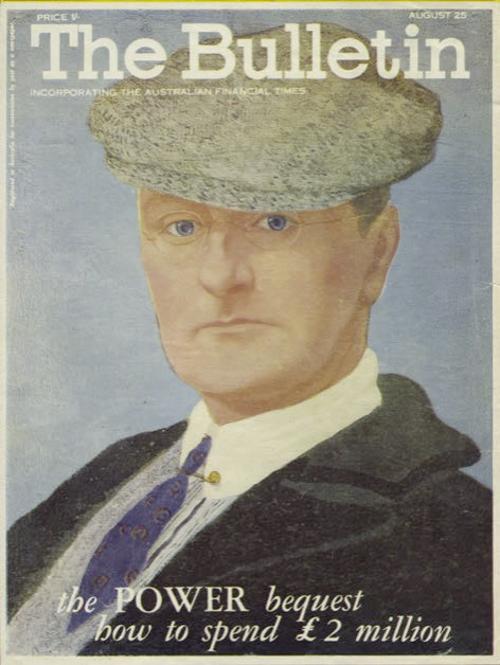

A brief description on the 32nd CIHA and its relevance in relation to art history and practices.

A brief but notable account of the 2008 CIHA from the perspective of Anne Kirker describing the key speakers and their topical lectures in relation to art history. Kirker further elaborates on her experiences at the CIHA and what she deemed intellectually stimulating and intriguing. Kirker also summarises the general relevance and opportunities the CIHA provides.

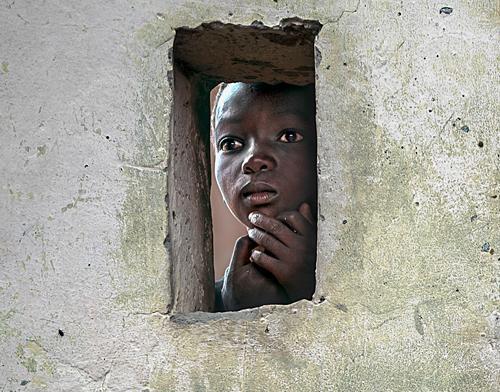

Tracey Moffatt’s series Body Remembers (2017) draws its title and responds to the poem by Constantine P. Cavafy (1918). In each of the series of large photographs we see a woman alone, in the ruins of colonial buildings, on the shadows of eroded stones. We see her looking out of windows, looking out into the distance. As the viewer, we see the back of the woman’s head, or the shadow of the woman, or her face that is covered by her hands as the Aboriginal woman maidservant looking out. The body in this title could be read as both our country and our flesh. The sovereign woman mourns. What do we mourn?