Lee Salomone's reclaimed objects have histories with roots both strong and deep. His works speak in silent reveries of earthy sound: the peeling of paint, the cracking of wood and the slow bending of rusted metal. Each object stems from its own long narrative, largely predating its exhibition status.

In the gallery a combination of wall-mounted works and installation pieces become landmarks in an architectural space, a combination of closed and open forms interconnecting and dispersing the gallery. The ability to move through and around objects seems to elevate the room into a sculptural space, a place of form and physics, mass, gravity and void.

It is said that it is the body rather than the brain that explores and remembers the world. Salomone's works, too, speak of a physical memory, of ages and histories etched in to the weathered crumbling of paint on wood. There is a fragility in the objects, but we are also aware of how each has withstood the sturdy test of time.

There seems to be a generational habit of hoarding amongst veterans of the Depression. The painstaking collection, storage and adaptation of random materials have come to signify an age of necessity and rainy-day accumulations. If we look at art as a form of storytelling, these works tell tales passed down from generation to generation. Zotti sifter (c1960) and Zotti basket press (c1960) really are family heirlooms made by Salamon's grandfather, telling of a creativity born out of necessity. The Zotti fly swat (c1960) is a strange contraption, made in the name of utilitarian practicality and ignorant of its own inherent qualities as an art object.

Alongside these objects, a rusted spade hangs, a simple lunar eclipse for a handle, whilst the artist talks quietly to visitors about gardening conditions during the waxing and waning of the moon. The circular motif is repeated again and again, each time drawing new speculation to our connection to land and, in turn, the land's connection to the sun and moon, our eternal cycles.

I imagine the lives these objects had lived, once new, then used, slowly forgotten and since re-found. How many sunsets these pieces of rust have witnessed, laid bare upon the land, half-buried like metal corpses in shallow graves. Australia is studded with these mass graves of rust and reconnaissance, and we have often come to adopt these veteran objects of the sun's obliteration as inherently 'Australian' artefacts. As such, visiting Lee Salomone's work is almost like coming home. As a relatively new country it is rare to meet people that do not possess distant memories of a rural past.

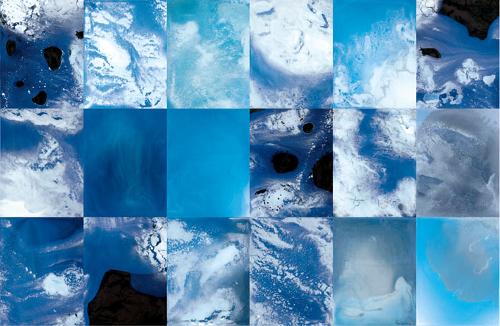

The works on display are a combination of found objects and reworked materials. Pieces of green hosepipe, the discarded remains of young petrol-siphoners, become lush landscapes, devoid of their water-carrying intent. Smoothed tree trunks house cavities flushed with blue flocking, a memory of sky or water, now empty and dry. A pile of newspapers caress a glass walking stick, never to be read again. And all along there is a silent reverie that hangs heavy in the room, like a funeral parlor, a repository of memories past. But these objects are not dead. Rather, they seem to buzz with an emotive energy, a new life.

Salomone writes that 'the found reflects and respects the texture of reality'. Indeed, there is a strong sense of respect for the materials at hand, with each one given its own space and adjusted only slightly by the artist's tools. He goes on to write that 'collecting is a quest for meaning'. This body of work acts almost like a series of signifiers for some unknown intent, like a bowerbird collecting bits of blue for reasons of which even it is unaware.

Letting Go is a poignant exhibition that explores the everyday and profound concerns of life, but equally revels in the mystery of the past.