Diversity and disruption in arts and health

Clive Parkinson, Director of Arts for Health, Manchester School of Art, in conversation with Jill Bennett

I am autistic. I perceive and experience the world through sensory and cognitive pathways unique to autism. Neuroscience documents this as “sensory atypicality” and “detail‑focused perception.” In terms of lived‑experience, this means the senses react in ways different from the norm, and the mind attends to minutiae that most others dismiss or miss altogether. Autistic sensory‑cognitive idiosyncrasy unpacks in myriad ways, varying from person to person and in modulations that range from intense attraction to extreme aversion.

I am in France. I have been working towards a presentation related to my research on panic at the Sorbonne, at a conference called Lire Pour Faire. I am anxious, sick with it, actually. My paper is dry and I need wet. The wet of tears, the wet of biochemicals pumping through blood, the wet of fear-piss. I want to vomit and I want to scream. Instead I sit in my room and hyperventilate. I find my friend and disclose my fears to her. I am in a state. She convinces me to do a practice presentation for a group of people who will be kind and supportive. I perform my disquiet and my insecurity and it is painful, and the pain is felt, and there is silence. There is a sitting back, a sinking down, a closing of laptop lids. There is quiet. Sometime after the quiet somebody tells a story and there is talk, feedback, questioning, exchange, confusion. This is where the research happens. Elsewhere, and otherwise, and afterwards.

Why I do them is to be around people that don’t have any fear.

I want to see what it’s like to be around people who are really happy.

Stuart Ringholt’s anti‑anxiety Anger Workshops and stress‑healing Naturist Tours step outside the usual model of clinical healing practices. They revisit the potential of being happy by living in the moment as a form of liberation and group therapy that is creatively driven. The first of the Naturist Tours began as part of a show on art and therapy named Let The Healing Begin (2011) at the IMA in Brisbane. Curator Robert Leonard commented that many regular gallery goers politely declined the invitation to take part, and although he was low key in his advertisement of this aspect of the show, it created a tremendous amount of community and media interest. Fast forward to the subsequent tours through the Wim Delvoye Retrospective at MONA (2011), and James Turrell: A Retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia, and Ringholt’s practice has all but surrendered to the demand, with an accelerated following.

I have lifted the title for this essay from Narratives of Dis‑ease (1990), a series of works by the late British photographer Jo Spence. The series was made following the artist’s partial mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. Closely‑cropped around her body, the photographs show Spence partially nude, using props and performing emotive gestures, compositions and sight gags that were suggestive of the sub‑titles she ascribed to each individual image: Expunged, Exiled, Included, Excised and Expected.

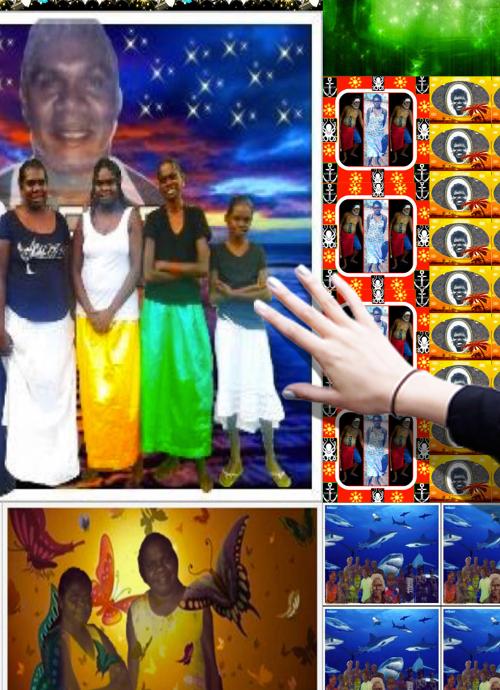

The affective power of a photograph is perhaps never more potent than when the subject is a lost loved one, as Roland Barthes famously discussed on contemplating a portrait of his dead mother. This appreciation of the role of photography is harnessed in a new digital artwork by the Miyarrka Media collective which uses family photographs, including many images of deceased family members, as the basis for an interactive digital artwork about the importance of family and feeling in an age of interconnection.