The picturesque is a troubling genre for Australian art, as much for the pleasure it gives as for its vision of a conquered land. Here, Chris Pease reworks the picturesque images of nineteenth century draftsman Louis Auguste de Sainson who sailed the south-west coast of the continent, to show us that these pleasures are not just one-sided. The investigative minds of the Europeans are mirrored by the fascination of the local Nyoongar people for those who have just arrived. In this series of paintings, Lewis Carroll's Mad Hatter looks first one way, then the other, hopping lightly between the picturesque and thick surfaces of Balga resin.

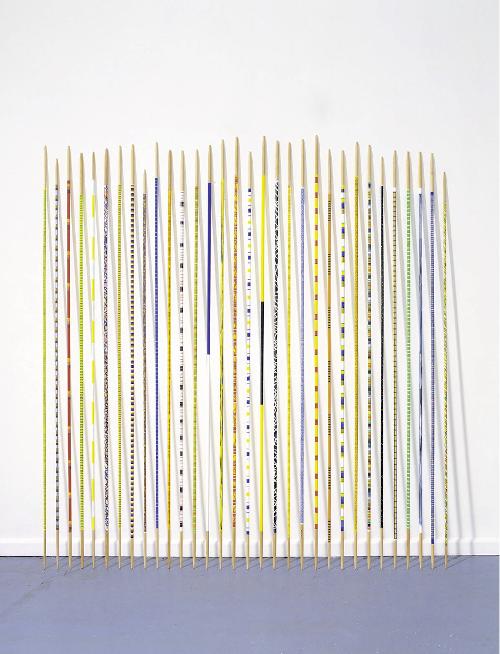

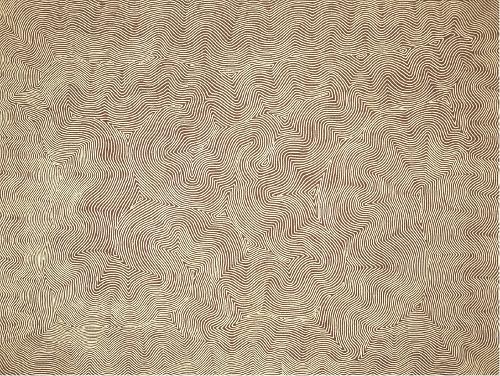

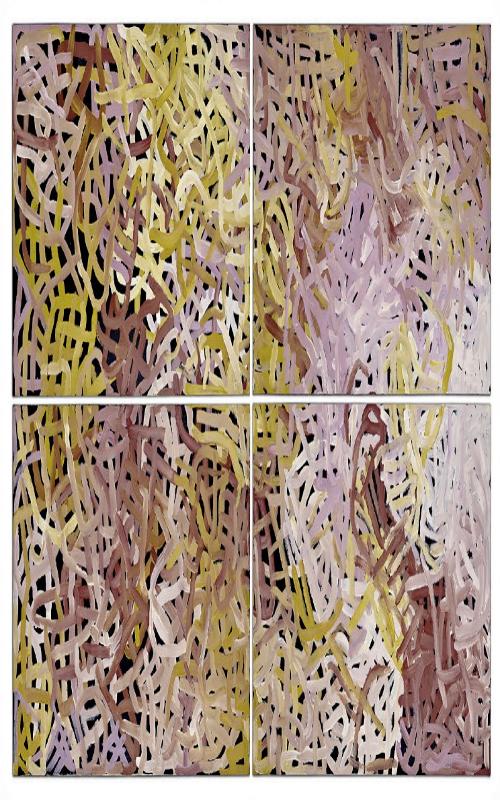

The resin is collected from the local Balga or grass tree of the South West, and melted onto hessian and canvas, bringing an intense, highly worked presence to these paintings. In Down the Rabbit Hole (2007) and Minang Boodjah (2007) it is applied to frame scenes of early contact, absorbing the brightness of Arcadian, picturesque days. Used by Nyoongar people for decoration and tool-making, it condenses into a dense spectrum of reddish brown. Balga Resin (2008) is a dense, 2 by 3 metre surface of the stuff, turning it from traditional uses and into a contemporary art that expresses the presence of living country. Pease turns here from a looking glass upon colonial worlds to a looking at the materiality of the world itself. The Balga is the stuff of place, the matter of the region, in an actualisation of the South West's sensibility. His hard-won methods for extracting, refining and applying it make for a kind of alchemy of the eye, which moves over and into it, as light is absorbed and refracted by its glossy darkness.

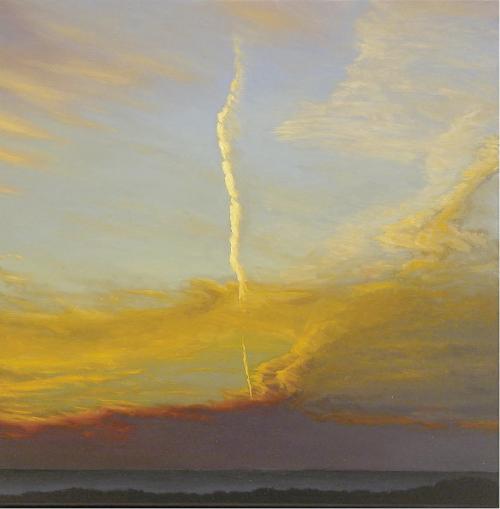

The only painting without the resin is Roundhouse (2007), but here too are signs of Pease's scientistic method and a synthesis of cultures as the Waugyal, or great serpent, towers over this image of colonial Fremantle. The Roundhouse Prison, surrounded by plain houses, marching convicts and a plague of rabbits, is dwarfed by the creature. Its scale and the mane that adorns its head and neck were described and drawn in great detail by Nyoongar and sailors alike. Here it rises from the ocean with strange, supernatural power.

Another work that bespeaks the twilight of cultural imaginations is Cow with Body Paint (2007). The cow has fur painted with what looks like bar coding, signaling the role that this animal has played in the subjugation of land while it has itself been subjugated, as part of the machine age of pasture and meat. The Waugyal and cow are monsters of sea and land, brought here from their place on the margins of civilization, and given a more proper scale in Pease's massive canvases. He foregrounds those creatures that have been repressed by civilization, beings more typically seen from the corner of the eye as they weave through a turbulent ocean or from the window of a passing car.

Cow with Body Paint is made with Balga resin and with an ochre mined from the south coast. The surface of the painting appears to lift with Pease's confidence in these very different materials. Its brown, black and red textures impress the tones of earth and wood upon each other, speaking of country like smoke from flame. Each of his paintings has a precise visual message, their experimental combinations of materials, their reworking of historical and childhood imagery, making a series of targets for the collective unconscious. Both Balga Resin and Cow with Body Paint begin to take Pease in a less figurative direction, shifting his work from the historical to the contemporary. Using materials extracted from country, and playing with iconographies of cow and sea monster, Pease alludes in this show to that which the postcolonial world does not and cannot see, the monstrosity of matter, meat and materials.