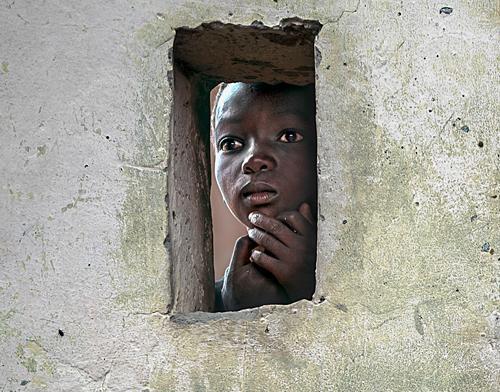

Escaping freedom: Towards a culture of mutuality

The one option no longer available is a return to an earlier order. Although there may be moments of calm there will never be peace again in our lifetimes, caught as we are between the ongoing crises of climate change and the social collapse of a disintegrating neoliberal economic order. Our contemporary culture is in transition as a new culture builds itself within it, each bit ferociously contested not by the left or right so much as the faction of compassion and mutual aid versus the faction of dominance and individualism.