Welcome to the Anxiety issue, which coincides with the launch in Sydney of The Big Anxiety: festival of arts + science + people. Three main factors have determined this focus. The first is that we live in ever more anxious times—a post 9/11 climate of fear and xenophobia, personified by Donald Trump and compounded by economic uncertainty. The second, in some ways linked to the first, is the increasing awareness that mental health is a significant issue right across society. The third is that art can do something about this.In June, the Australia Council published the results of the latest National Arts Participation Survey. Sixty-seven per cent of young people, it revealed, now value the arts for “helping us deal with stress, anxiety, depression.” In July, the report of a UK Parliamentary inquiry, Creative Health, presented resounding conclusions regarding the benefits of art for health, noting in passing that Australia is at the forefront of this field.

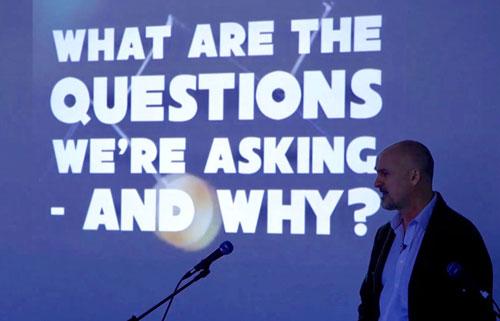

But what is “arts and health” and what is its relationship to the wider contemporary art world? As Lord Howarth writes in the foreword to the UK report, there is a “chronic and sterile” stand-off between two camps: the proponents of art for art’s sake vs. those who promote the practical, community benefits of art. This schism still shapes much of our sector, in spite of the many projects that imaginatively cross the divide. In an interview during the last Sydney Biennale, for example, Artistic Director Stephanie Rosenthal warned that art could do no more than “talk about” political matters, insisting, “you’re cheating yourself if you think you’re going to change the world.” We launched The Big Anxiety precisely to challenge this separation and to create a space in the cultural landscape where art and action could be explicitly linked and tested—where art could, if you like, change the world.

If there is a domain in which the impact of art is palpable, it is surely mental health, an area where the capacity for self-reflection and empathy, for exploring and contesting labels, for developing narratives of experience, is fundamental to recovery and wellness. More specifically, art provides a proactive response to anxiety, which is not only a clinical disorder but a state of perturbation and disquiet, a sensitivity to chaos—a condition that requires that we reimagine our social connections, and agency.

Changing the world is not a question of scale (although the greater the investment, the bigger the result). It is a conceptual reorientation toward engagement and the possibility of change. The projects discussed in this issue have this in common: they are outward facing, even as they address the intimacy of emotional life—concerned with their potential for connection and impact beyond the artworld itself.

.jpg)

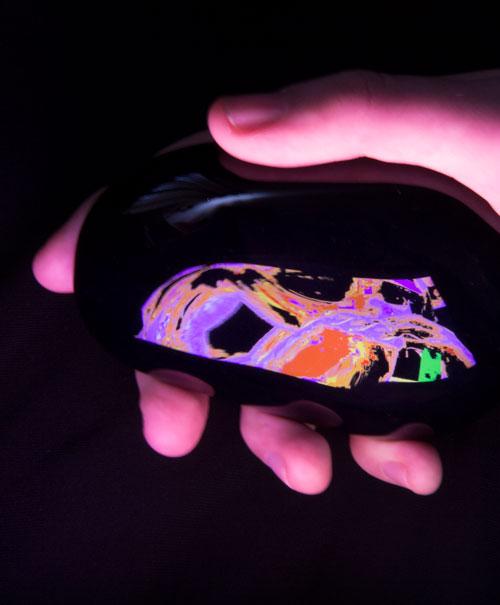

As Clive Parkinson, Director of the Arts for Health program at the Manchester School of Art and I discuss, this need not mean that art is instrumental or subservient to a health agenda. The most celebrated artists from Van Gogh to Emin have captured the unruly dimensions of the human mind. For arts and health practitioners, such aesthetic expression is a point of connection; for mental health researchers, it is also potentially rich data—as in the case of our cover image, Landscape of the Mind, an installation created from body maps, depicting the sensation of anxiety. These body maps were developed by participants in workshops led by the Black Dog Institute as part of the lead up to The Big Anxiety. They are the outcome of a three-way collaboration, bringing together art, science and people, and of a research project that is driven by a focus not on medical diagnosis or brain chemistry but on the lived experience of anxiety.

Such a concern with experience is radical and necessary in mental health. Radical because it focuses on people but also because the data and the methods for such inquiry will come not from medicine but from arts. We have a lot to gain from aligning art to the larger goals of social care. But we always need to counter the forces that seek to reduce art to simple, measurable outcomes or to some illustrative role. In this issue, we invite you to envisage the complexity and promise of art in relation to psychological wellbeing and mental health.