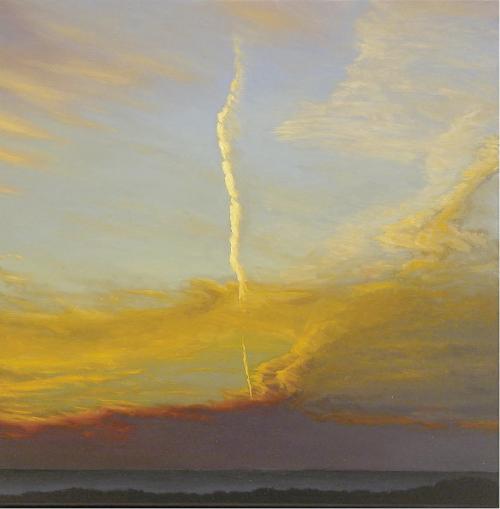

This exhibition takes paintings, artefacts, photographs, film and sounds from the development of the Western Desert art movement from 1972-1981 and presents them as a slice of art history that is also social and intellectual history. It is, as its curator Vivien Johnson says, 'one of the most compelling stories in Australian art history'. Following the Aboriginal artists' own way of dividing time the story is told through the division of the years into the name of the then current art advisor, so there is Peter Fannin time 1972-75, Janet Wilson and Dick Kimber time 1975-77, John Kean time 1977-1979, and Andrew Crocker time 1980-81. Unlike most histories of Western Desert art the story starts after Geoff Bardon had left Papunya. This seems a little odd but the purpose of it is to take the emphasis off Bardon and back onto the lives of the artists. The exhibition is alive with colour:- the walls of the gallery are painted to match the paintings; the red red earth on which the artists sit to paint is present in photos and actually in the gallery as a bed of red earth from Papunya has a panting displayed upon it; the vivid pinks and yellows, reds, blacks and whites of the paintings spotlit under halogen lights are accompanied by recordings of the soft deep timbre of the artists' voices singing or talking as they paint. Thus the communal aspect of the works as belonging to the places where they were made and the people who made them is intensely conveyed.

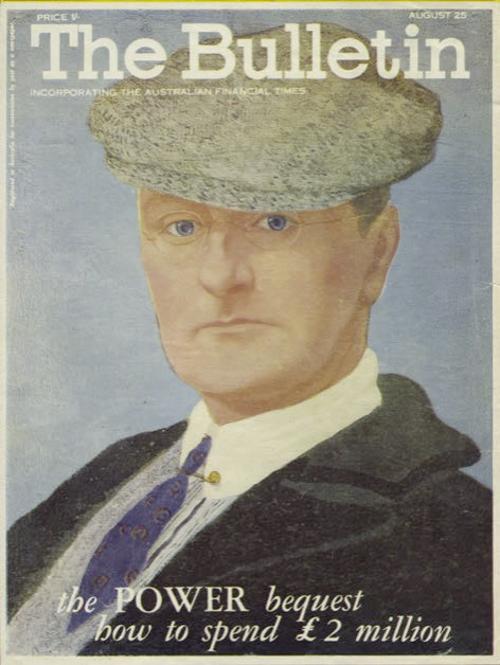

Johnson is about to publish a monumental book Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists (IAD Press, Alice Springs). Her devotion to Western Desert art is legendary and warm. Her personal and professional connection with the artists and the art go back to 1980. At the forum accompanying Papunya Painting at the National Museum of Australia on the last day of the exhibition she recalled the familiarity for her of the 'punk aesthetic' of Kaapa Tjampitjinpa who when she first met him was wearing an old suit jacket with about fifty-two safety pins holding it together. Johnson's first word of Western Desert Aboriginal English was mutukariwan (motor car one) meaning, not as I first thought a motorcar size canvas though it does mean a big canvas, but one that will sell for enough for the artist to buy a motorcar, often an overpriced secondhand car that breaks down on the way home. And in the catalogue John Kean describes Shorty Lungkarta Tjungurrrayi buying a 1959 Holden in 1977 with the $1,000 cheque he got for painting a mutukariwan.

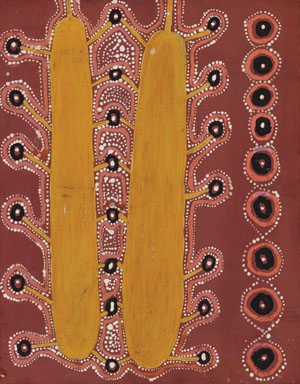

Johnson was a sociologist before she was an art historian and one of her main concerns is to demonstrate that Western Desert art is 'more than art', it is title deeds, it is related to land and the Tjukurrpa (Dreaming), kinship, Aboriginal society and ceremony. She reminds us that when it was first shown it was too ethnographic for art galleries and too contemporary for museums. In the beginning the art was usually displayed with long explanatory stories while nowadays since it has become a genre of world art and a ubiquitous part of Australian contemporary art that seems always to have been here, it is presented without much explanation. What is often lost in this presentation is recognition of the complex and significant connection of the paintings to Aboriginal society however smoothly they have now fitted into the marketplace as commodities.

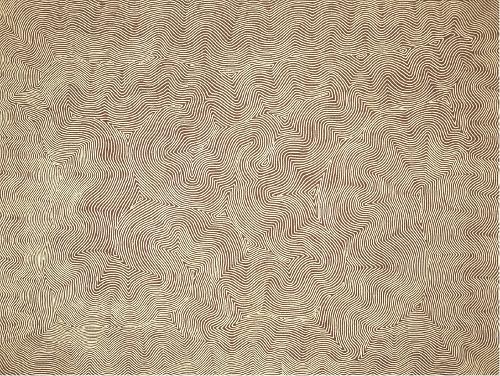

Almost all the paintings on show have not been exhibited before and are in the collection of the National Museum of Australia, a collection they inherited from the Aboriginal Arts Board which supported the painters by acquiring works in this critical decade when they were not yet world-famous. One of the art historical purposes of the show is to familiarise the viewer with the names, personalities and styles of various artists so that in the future they may recognise them, so that they may become part of our art vocabulary. Thus we see memorable photographs of Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula with a paintbrush through the hole in his nose, the beaming smiles of Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, George Tjungurrayi and Long Jack Philipus Tjakamarra as well as their paintings to study. Many paintings are experimental though most, Clement Greenberg would be pleased to see, are flat. A few are remarkably like mosaics. Though an introductory note by Michael Pickering talks about the pieces of foreign matter trapped in the works like hairs and seeds it is really the crispness and delicacy of the work that is more striking than any roughness in it.