Full disclosure: I was involved (panel member) at the rather cerebral Sydney launch of this book. Sheepish confession: I still don't quite understand where blubberland is located or what blubber is, this despite the fact that the index promises us a definition on pages nine and ten.

Go there, and you'll find that blubber is unused energy: whale oil for lamps, the flesh of a fruit, 'the yeasty bounce of a baby's thigh designed to sustain life through cold and famine'. It's 'anything spare or surplus ' (so not a lot like a baby's thigh, then) and it's 'the crack where the light gets in.'

But it's also the opposite of light. It's the couch potato, the quadruple-garaged McMansion& I could go on, but it wouldn't get a lot clearer. Suffice to say that this is an interesting, though somewhat diffuse (blubbery?), look at the way we live now, taken through the prism of Ms Farrelly's specialty, which is architecture.

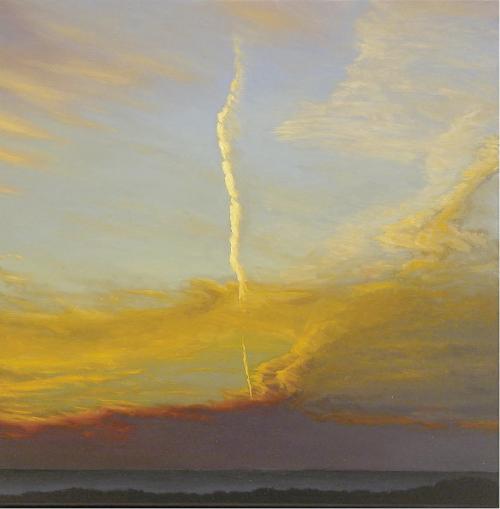

It's also about how the way we live is shaped by what we want. But, as Ms Farrelly knows, sometimes we are not quite sure what we want, and about nothing are we quite so ambivalent as beauty. Once upon a time – well, once, or more than once, upon several times, in fact, during most of history – truth really was beauty and beauty truth. Beauty was an objective quality of things, not a thing in the eye of the beholder. Then it became a matter of taste and, shortly thereafter, came under attack from the modernists.

Now, despite occasional rumours of its return to intellectual respectability, beauty has been confined to blubberland. This doesn't mean that we're uninterested in beauty – young girls smoke and starve themselves in order to achieve what we call female beauty these days – but it's the meaningless beauty of the shopping mall and the designer collection. Or, on what might, or might not, be a higher level of achievement, we get Prince Charles's model village of Poundbury and the homely products of New Urbanism like Seaside, Florida (as featured in the movie, The Truman Show).

This account, though broadly true, suffers from a certain narrowness of focus. It seems to work for art and architecture, but does it work for music and literature? In music, for example, the story is much more complex. Here, the most notable in-your-face modernist gesture was Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone scale. This is a compositional device, intended to restore order to a world in which, after Wagner, tonal order had broken down. It is not intended to produce anything ugly, though – given that, through most of Western musical history, extreme chromaticism has signified tortured emotion – nothing composed with it is likely to make us feel comfortable. On the other hand, Schoenberg's pupil, Alban Berg, produced in his violin concerto a work of extraordinary beauty. It's true that Berg's opera Wozzeck is, by and large, an ugly work, but beauty is not all we demand of music. This is a drama of the greatest emotional impact. (For that matter, the late, black paintings of Goya aren't exactly nice to look at.)

Literature is another complex case. To take just one example, Ezra Pound was a poet who systemically undid his own great lyric gifts, but even he could achieve moments of highly wrought beauty in his late Pisan Cantos.

When it comes to the visual arts, though, Ms Farrelly is on sure ground. She can point to the Dadaist Tristran Tzara expressing 'a mad and starry desire to assassinate beauty', Picasso admiring Degas's 'pig-face whores' and Paul Cézanne, 'a consummate draughtsman', undoing his gift for beauty as Pound was to do after him. In architecture, she can point to the machines for living in of Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius and to Adolf Loos, calling ornament crime and the urge to ornament a primitive one. He wasn't quite ahead of his time there: I remember from my childhood hearing Lord Clark of Civilisation pointing out how these days we prefer the savagery of a Viking longship's figurehead to the frigid beauties of the Apollo Belvedere, and Ms Farrelly is able to refer to Paul Keating: 'that which is primitive is more pure'. (Tell that to a young circumcised girl, Paul.)

Come the eighties, there was still beauty but, as Ms Farrelly points out, it was 'skin deep at most': Venturi and Gehry finding new ways to make sheds look interesting – curvy and sculptural or as bright and glittering as Vegas.

Later in the book, Ms Farrelly turns her attention to kitsch, which is the homage that vulgarity pays to beauty: 'Pretty soon Australia's entire eastern seaboard – famed for its barefoot, sand-between-the-toes charm – will be lined, three streets deep, in the marble-veneer and smoked-glass balconies, the roundabouts and air-conditioned malls that have come to spell civilisation. Full membership of Blubberland, she tells us, requires a determined tolerance of this sort of inauthenticity. It is a deceit.

It is a particular sort of deceit, neatly summed up by Ms. Farrelly's observation that Sir Les is simply bad taste while Dame Edna is kitsch. It is not just deceit but euphemism, denying not just shit, but, perhaps more to the point, death. And this, maybe, is where this fascinating and witty book is leading us. Kitsch denies death, but beauty, true beauty, leads us – or should lead us, or used to lead us – to a vantage point beyond death and beyond ourselves.