The derelict Tepid Baths is an inspired choice of venue for an art intervention/event. Whether intrigued by the idea of an outdoor pool in Hobart, curious about what lay behind the boarded-up façade, or a survivor of its infamous stick-wielding swim instructor, everybody knows this site and seems to hold a personal stake in it. Consequently, the opportunity to lawfully enter 212 Collins Street was as big a drawcard of the ONO Project as the art temporarily housed inside.

Over four hours on one Saturday evening more than 200 people explored the labyrinth of concrete rooms, the dry dive and lap pools, and sidled through a matrix of exposed framework of the upper level. Meanwhile, sound artists performed in a hall-like space that opened onto a barbed wire lined balcony overlooking the street. With no electricity, this event began by an afternoon glow but as it got dark the building was illuminated from within with generator-powered work lights, and dozens of little battery-powered light bulbs and torches.

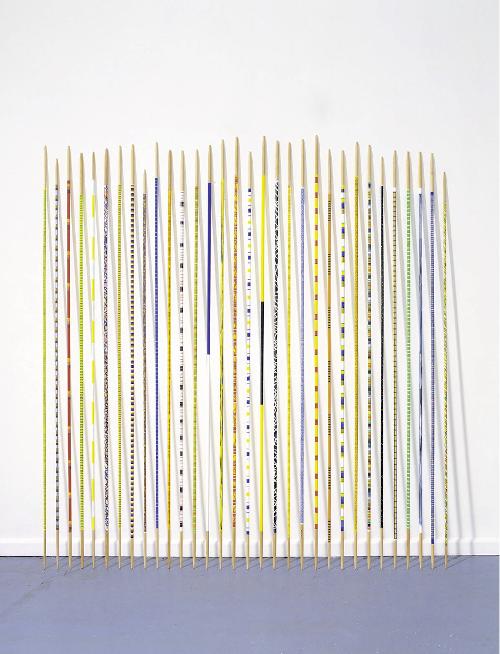

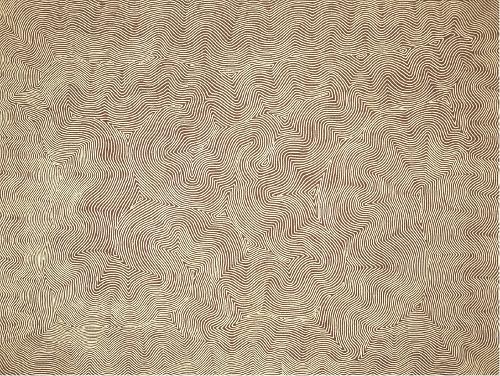

Pre-existing graffiti adorns almost every surface, indicating a history of unofficial use over many years. Thus the seventeen visual artists in the ONO project had the challenging task of intervening into a space that was already full of materials and graphically rich. Scot Cotterell responded by returning the walls of one room to the original institutional beige before meticulously covering them in calligraphic free-form line work, which drew on the aesthetics of tagging but abstracted and amplified the effect to produce an intense, immersive experience.

Moira Corby's performance/installation generated work in situ. Sitting in a cubicle in the girl's toilet, the artist used graphics tablet and projection to produce digital portraits of audience volunteers who queued patiently for their turn clutching numbered kick-boards. Lachlan Conn and Michael Prior utilized cardboard and other materials found onsite to create an adult-scale cubbyhouse complete with flags and 'cowboys and Indians' picture books, a playful reflection on makeshift occupancy. Andy Vagg tackled similar themes in building upon the material accumulations of a resident squatter to create an enclosure from secondhand clothing, the disturbingly intimate experience of which was like being nestled into the armpit of a stranger.

Kirsty Madden contributed two of the works that intervened most sensitively with the site. She was responsible for a whimsical installation of flowering weeds suspended from the ceiling with ribbons that cascaded to the floor to release fluffy seeds that drifted through the upper level. She also spray-painted a voluptuous bandit daintily sneaking through the window of one of the external walls. The strong representation of female artists in ONO was welcome recognition that the street art genre is not as lad-dominated as its image would often have us believe.

This was a showcase of predominantly emerging artists, not all of whom met the challenge equally well. The fate of the weakest works was obscurity, it was hard enough in the best cases to discern where the newest interventions (those of ONO that is) started, ended, and overlapped with other features of the venue. This is a familiar predicament for artists working within the street context, and several graffitists successfully combated that risk through repetition and variation of recognisable, and often appealing, motifs and characters. With the exception of street artist Ghostpatrol who could not resist the urge to inscribe their name across the base of the pool, the lack of concern with enforcing artists' discrete identities made for a refreshingly holistic viewing experience.

Organisers/curators Kate Kelly and Pip Stafford are now considering ONO as a six-monthly happening. The challenge for them will be maintaining the sense of spontaneity associated with this first event, and securing future venues as successful as the Tepid Baths turned out to be. If they can repeat their formula of strong partnerships with private owners, city council and heritage authorities, attracting energetic local and interstate artists, a minimal budget and freedom from the burdens and restrictions of external funding, there is good reason to feel this event holds exciting implications for attitudes towards public art in this city.