Due to timing this is a preview rather than a review but includes an interview and bears witness to the fact that Martin Smith is on a roll. It's been a busy year for Brisbane-based Smith, not to be confused with the British ceramicist of the same name or all the other Smiths out there. The Queensland Art Gallery has recently acquired two of Smith's works, he's got a book due to be launched this October at Melbourne's Centre for Contemporary Photography, and he's even participating in Fremantle Arts Centre's Bon Scott Project. His work is being represented at the Melbourne Art Fair by Sophie Gannon and he is talking to New York and Los Angeles galleries. Oh, and his partner is expecting their third child.

Just now, however, Smith is preparing for his solo exhibition at Brisbane's Ryan Renshaw Gallery, his third. Entitled In response to conversations with a therapist as a narrative device it's a mixed-media presentation combining large-format photography with Smith's quirky and distinctive skills as a story-teller.

'The storytelling came from when I started looking at my old family photos and thinking about what goes with them,' Smith explains. 'You know when you're looking at family photos, there are particular stories that go with them - that's that person, that's the time when your uncle turned up for Christmas, and so on.'

'Photography captures the classic moments of life, like your first day at school,' he continues, 'but it doesn't capture the other parts of your life that are sometimes way more significant.'

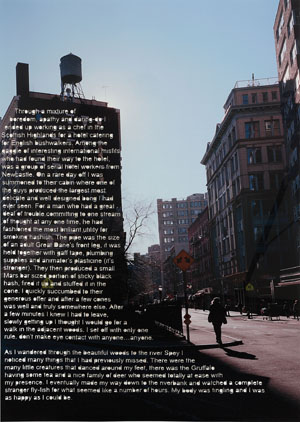

Smith's stories give a whimsical and highly personal account of his life as an artist – like his ill-fated attempt to become an actor with the Sandgate Amateur Theatre Group I then went up and told my ridiculous stories (2008) or the time he worked in the cutlery crew at Australian Airlines On any given day (2008). The lettering for his text is actually cut out of the photographs, giving them what he readily admits is a kind of sculptural quality.

'Each letter is hand cut out of the photo, so there's only ever one made ... which goes against a lot of the mechanical easily reproducible aspects of photography.' With the alphabet soup of cut-out letters that are left over, Smith has constructed sculptural works in a kind of ironic paper mâché. These elongated animals look like wooden carvings left over form the church fête where some embarrassing but untold event occurred. 'The memories are left behind and then reconstituted and turned into other things, it's a language constantly getting churned up. Memories are things that inform taking the photo,' he tells me, 'and I'm bringing some of the intrinsic aspects of the photograph with me.'

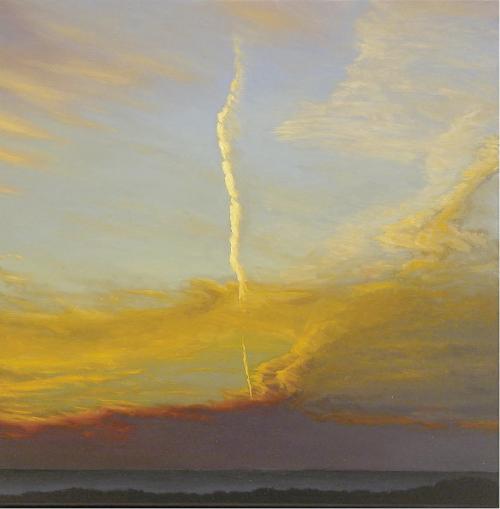

People spend a lot of time in a Martin Smith exhibition reading the works and then laughing or sighing in recognition. The photographs are all of fairly impersonal exteriors, almost crime scenes, not postcards, not picturesque snaps but odd disregarded corners of the world. In some way they are reminiscent of album covers or slightly lame posters but are brought into the present by Smith's honest and often very funny tales of modern living. Yet there are many threatening undertows in the work. Like Tracey Moffatt's Scarred for Life series the stories they tell are often grim and Smith's cricket bat bears the words 'are you waiting for the darkness Daddy'.