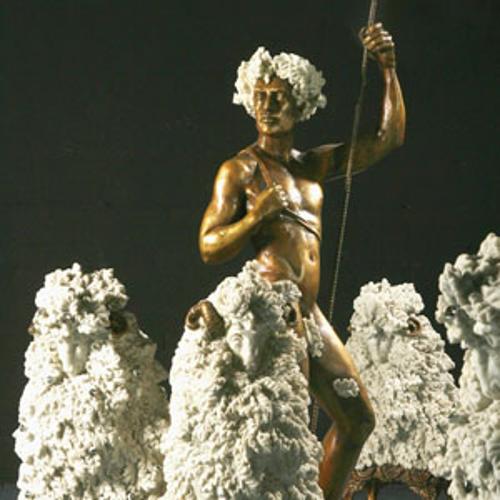

In her controversial 2003 book The Boy, Germaine Greer seeks to 'advance women's reclamation of their capacity for, and right to visual pleasure' by celebrating the fleeting eroticism of boyhood. Gallantly roaming through the history of Western visual representation and gathering a trove of ravishing images on her way, from Caravaggio's provocative urchins, to Michelangelo's languorous Dying Slave, to Eakins' supple-skinned bathers, Greer contends that since the early nineteenth-century there has been an attempt to purge boyhood of its former sexuality. For Greer, a patriarchal effort has been anxiously upheld to protect against the father's fear that his son will replace him as the focus of female attention, the same fear, Greer suggests, that drives older men to send boys to war.

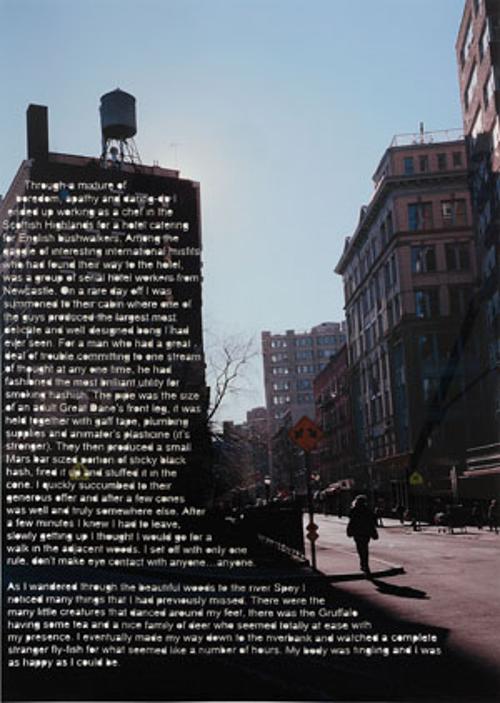

Read in this context, Angela Lynkushka's recent exhibition Now that I am a man I can go to war appears more open-ended and possibly less moralistic than the title first suggests. Seeking to intervene into the thoroughly gendered economy of visual pleasure, the Melbourne-based documentary photographer's exhibition addressed the politics of masculinity and contemporary discourse around the female gaze. Treading a well-worn path through what has historically been considered hostile territory, Lynkushka's attempt to explore new possibilities for female spectatorship is commendable, but at times uninspired.

Turning her lens to a group of teenaged and twenty-something men she had known for many years, Lynkushka invited each young man into her home and photographed him shirtless in her bedroom and in other domestic interiors. Promoted as a collaboration between the subject, the photographic medium and the artist, the work entered into the fraught relationship between visual pleasure and beauty, where beauty was found to reside not in a set of objective, formal properties, nor in the eye of the beholder, but rather in a complex interaction between subject and object; a slippery, performative act of communication and discovery.

Upon entering the exhibition, the viewer was greeted with a sequence of eight life-sized, unframed photographs of anonymous male youths, all on the cusp of adulthood. Looking away from the viewer and with their faces concealed, each subject was identifiable only by the title of the work itself: Souleymane, Simeon, Michael, Harry, Vatche. Hung side-by-side directly at eye-level, the seemingly oblivious figures were each positioned as objects of the gaze, captured in various moments of quiet introspection and vulnerability. Vatche might have been crying, with his downcast head and self-protecting stance, whilst the despairing Harry rests his head in his hands, trying unsuccessfully to block out the harsh light of a new day. Simeon stood erect, shoulders square and muscles tensed, but his pensive stare into dramatic black shadows suggested an anxiety simmering beneath his macho reserve.

On the gallery's opposing wall, Lynkushka presented five more portraits of mostly the same young men, this time with their faces exposed. Staring outside the frame, the whole time feigning ignorance of the photographer's (and spectator's) admiring fixation and invasive presence, these models appeared coy, self-aware and conscious of both their sexuality and the potential for its objectification.

Finally, connecting these two clusters of photographs was one lone image of androgynous Thomas, a camp young man heavily decorated with red and white makeup. Aesthetically incongruous with the rest of the series, and conceptually hackneyed, this theatrical re-imagining of male sexuality here underscored, and undermined, the much more subtle game of identification and objectification taking place elsewhere throughout the exhibition.

At a time where society has in fact become saturated with images of commodified, Gen Y male youth and beauty, where boy-bands and male strippers and celebrity sportsmen have replaced Eros as symbols of idealised masculinity, Lynkushka's exhibition offered a refreshingly alternative visual economy. However, despite her (and our) prolonged, intense attention to her subject and the aching discovery of fallibility and imperfection in boyhood, her photographs ultimately failed to create the sense of intimacy and empathy that she so desired.