Search

You searched for articles ...

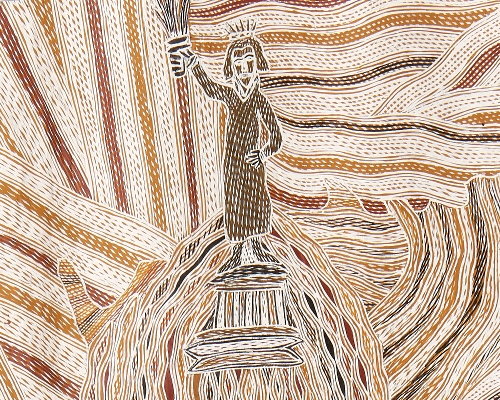

If you’re ever gifted the good fortune to head out for a game of two-up with Uncle Badger Bates on a Friday night in Broken Hill you’ll see firsthand the magic he holds, and most of all how much Unc has in the tank. I’ve been privileged to do this several times during visits to my Barkandji homelands, and I’ve almost always struggled to stay ‘til stumps. Not so for Uncle Badger whose passion for the spin and his never-ending energy to talk and laugh and tell incredible stories puts all us ‘young ones’ to shame. Hosted by the famous Palace Hotel, two-up is one of the many quirks of my Mum’s hometown, being the only place in Australia where this game is played legally every Friday night, year-round: The Wild West.

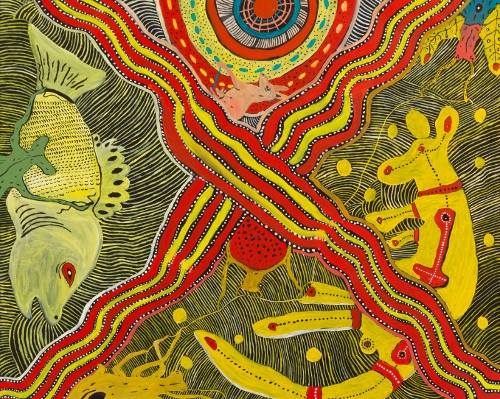

Mark-making in all its interpretations is at the core of everything Teho Ropeyarn enacts through his art practice. He might even agree that mark-making is his purpose.

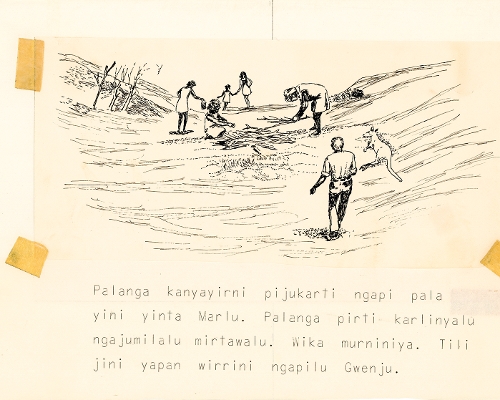

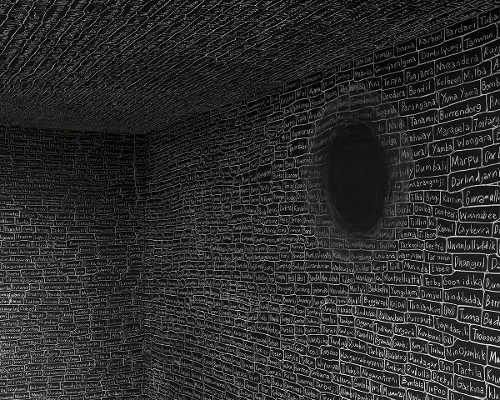

We can ask why did the first being make the first purposeful mark ever, anywhere? For remembrance, which is sharing knowledge. For First Nations peoples, for 65,000+ years, remembrance is manifest in the complex systems we pass on for Knowledge, Kinship (Moiety) and Lore.

Our culture and traditions were mostly passed down orally through the generations and were also recorded in our sacred rock art painting, engraving and carvings. We made artefacts, masks and canoes.

When Moa Arts (Ngalmun Lagau Minaral) started in 1999 our major objective was to record and preserve the cultural knowledge so that it would be available for future generations of Torres Strait Islanders. We were very fortunate to have our artworks exhibited nationally and internationally, which built the foundation of the Torres Strait Islands’ print tradition.

How does one hold the legacy of their mother, teacher and friend?

How can one honour the stories that have been passed down?

How do you represent one and their stories and legacy when they are gone?

When they are gone, but still here?

Laurel Nannup is a Birdiya — a leader. Often working in partnership with her son Brett Nannup, the duo have masterfully utilised the print medium to hold and transmit their Noongar culture. Their work tells the stories of our Nyittiny — cold times or creation time, while also investigating and unveiling notions of place, self and one’s own personal stories. Many of Nan Laurel’s works tell her story of childhood and upbringing; what it meant to live in a white family’s home, the story of her mum taking her from Carrolup Native Settlement as a baby to live in Pinjarra, until she was taken.

Loreto Prison

1-.2.'76

Dear Mum & Dad,

How are youse? I’m fine. I settled into school really well. Once I got on the plane I was right. Haven’t shed a tear or been homesick since I left A/S [Alice Springs] Airport…I’ve only been back at school a few days & I’ve been in trouble twice. Troubles my name. Last night Mary nearly made the bed collapse. Mary & I sleep in a bunk with me up top. This was after lights out. Sister Strict heard & she came roaring back in & Mary & I were sitting laughing like two hyenas. Was she mad! Sister Domonic told me off tonight. Stupid old bat!! Eric rang tonight. Telling me about the rain etc. up there. Gee, just to think if we’d been say a day later into town we’d still be home. I’m ringing this weekend - probably...How’s the animals? Especially the horses. Say hello to Tycho, Jinka & Blue for me. How’s my boyfriend (Explorer) going? Are his cuts healing well? Is Sabrina filling out? The rain came in time to put feed in the mares paddock. I suppose the rain puts a stop to all ideas about mustering etc? Hint: How about home in Easter. Christmas, Birthday present rolled into one. Love it…I’m trying hard at school Dad. Still want to go home after 3rd Year.

Lots of Love,

You Know Who (Convict at Loreto Prison)

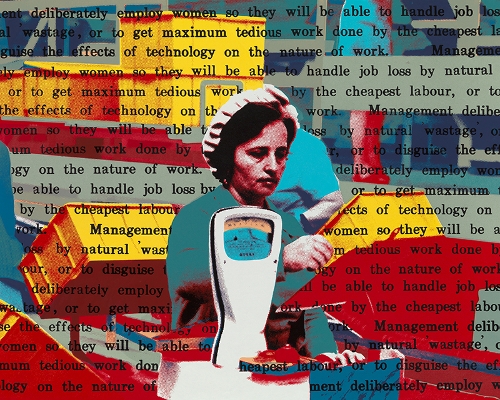

I was living in Yallingup in the southwest of Western Australia in early 1989 when I learnt via the community grapevine that a new arts program designed for Aboriginal women was soon to happen in Walyalup/Fremantle. I was intrigued, and as I was taking leave from my teaching degree, it was great timing.

The traineeship was led by the dynamic and visionary Noongar woman, Margaret Drayton, and taught by leading women designers and technical experts; it sat under the banner of Women in Work, supported by the Department of Education Employment and Training, providing opportunities for women to gain skills and experience to help them enter the workforce—in this case, the arts industry.

We are told to listen to the Country,

but have you ever spoken to it?

Have you read Natalie Harkin’s poems to sheoak trees

or called out to birds that flood the skies above you

or touched the exposed face of a mountain to announce to it your presence?

I have.

These individual acts are spiritual, and effect loving communication

between us and Country.

Our people know the strongest reciprocity to Country is enacted through collective communication. Be it dancing, singing or any mass cultural gathering of mob. The collective spirit we can raise is more powerful than any individual action. It is essential we continue to communicate with Country, just as our old people have in the forever. Country wants us to speak, sing and create for it and for ourselves. Together we must animate our relationship to keep Country and community strong and healthy. For mob, even the smallest action of acknowledging Country is ceremony, and the collective conjuring of spirit is the ultimate form of storytelling.

I saw the sun

I sang my song

I danced my dance

I saw my shadow

I saw my soul

I made my mark!

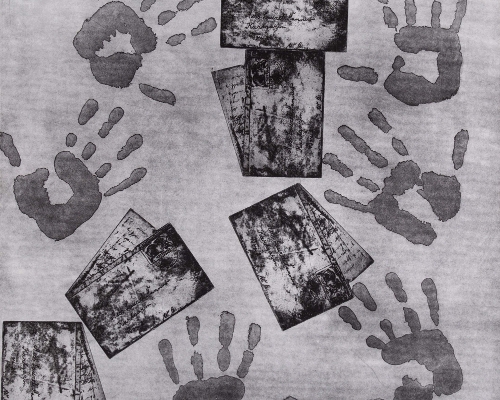

Historically, Aboriginal people across the continent, whether intentional or casual, could identify the presence of another named person from their indexical mark; footprint, handprint, bum print or body print. It was the first art, and marked this site as my land. This idea was behind my performance I saw the Sun, in 2004, under the Story Bridge in Brisbane, in which I stripped down and danced as the rising sun left my mark as a shadow (the ancestral spirit) on the river’s muddy shore. Made into a video, it was included in two exhibitions in Brisbane in 2004 and 2005.

_card.jpg)

This article featuring selected paintings by the multimedia artist Khaled Sabsabi was commissioned and drafted well-prior to the furore surrounding his celebrated appointment (with curator Michael Dagostino) to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale. The appointment was rescinded only six days later. As an art historian undertaking the unruly task of writing about contemporary art as a type of future history, I feel compelled to contextualise my original article, which I proposed as a reflection on Sabsabi’s more contemplative material practice.

The last essay I contributed to Artlink examined recent curatorial efforts to insert Philippa Cullen (1950–1975) into the canon of Australian feminist performance art history. The revisionist energies amplifying the contributions of an emerging experimental artist of the early seventies, were institutionally performed via the National Gallery of Australia’s (NGA) Know My Name project. As important as the project has been in critically redressing gender imbalance and historical gaps in the NGA’s collection, it stirred great debate and highlighted the multitude of important female-identifying and non-binary artists, living and dead, who fail to cut through.

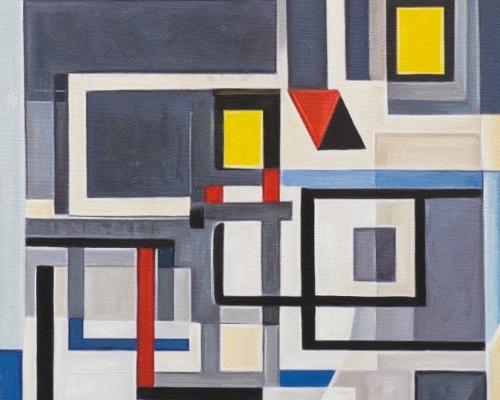

In August 2024 I joined Wollongong Art Gallery as its seventh director in its almost 50-year history. Immediately immersed in its large collection as a crash course in its cultural and sociopolitical contribution to Australian (largely regional) art history, I kept returning to the enigmatic work of a local and long-forgotten painter Joan Meats (1920–2003).

April 2025 marks twenty-five years since Rusty Peters (Dirrji) and Peter Adsett painted Two Laws One Big Spirit at Humpty Doo near Darwin. The fourteen canvases—seven pairs, in formal association with each other—are now permanently housed in the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), gifted by GRANTPIRRIE.

A quarter of a century is a long time in the politics of reconciliation, the framework within which the series has mostly been discussed. ‘A dialogue in paint’ as Adsett refers to the career-defining project, the works are evidence of a correspondence between unlikely painting peers, born of acutely different world views and visual vocabularies.

A lover whilst exiting my life, turned to say “l never really loved you. l loved your art.” It wasn’t the biggest burn. I consider myself the art anyway. It’s the best part of me. Really, actually, the only me. There is so little of me (‘my’ life). I have extra territory to make a variety of art personas.

- Diena Georgetti, in conversation with Melissa Loughlan 2025

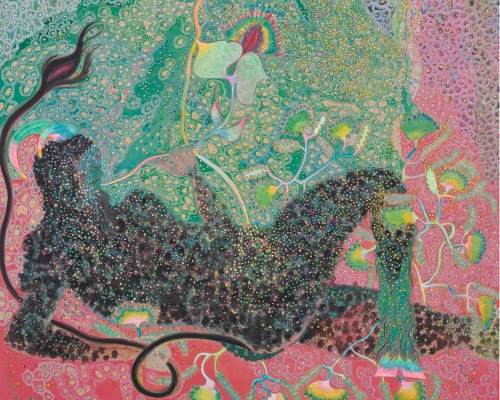

Diena Georgetti’s recent paintings eschew anecdotal narrative, but nevertheless conjure a labyrinthine backstory that interweaves a complex stratum of influence, personal necessity and artistic identity. It would be more than glancingly accurate to see these works both as insights into the dichotomy between creative impulse and control, and as vehicles to some place of release or repose.

Organic matter turns into compost when it breaks down.

After brewing my cup of tea, I place wet tea leaves into my kitchen’s compost bin along with other food scraps, which I later add to my garden’s compost.

Compost over compost.

Time over time.

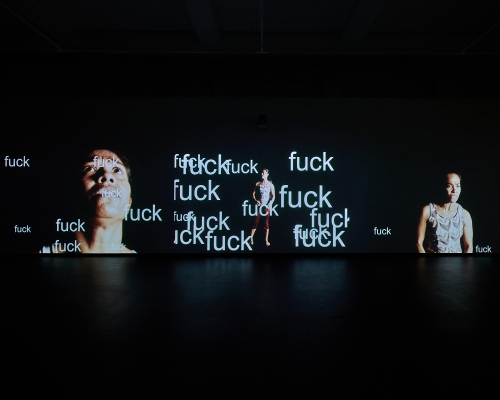

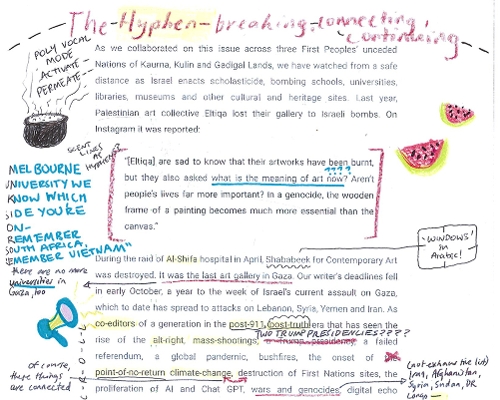

I write these words at exactly one year of ongoing brutality and genocide in Gaza, during the 76th year of Zionist occupation of Palestine.

I can’t help but think of what else belongs in a compost bin.

Zionism.

Militarism.

Capitalism.

Colonialism.

Extractivism.

Expansionism.

What other words that end with ‘ism’?

Which outdated world views, ideologies, systems and structures belong in a compost bin? What skeletons and bones need to break down to birth something new?

Queensland is the most decentralised state in mainland Australia, with more than half of its population living outside its capital. Gimuy/Cairns, a city of approximately 150,000 people, is closer to Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea than it is to Brisbane. A gateway to the Great Barrier Reef and the World Heritage Listed Wet Tropics rainforest, Gimuy/Cairns is a both a tourist destination and a regional centre, in addition to serving as a vital services hub for communities on Cape York and the Torres Strait Islands.

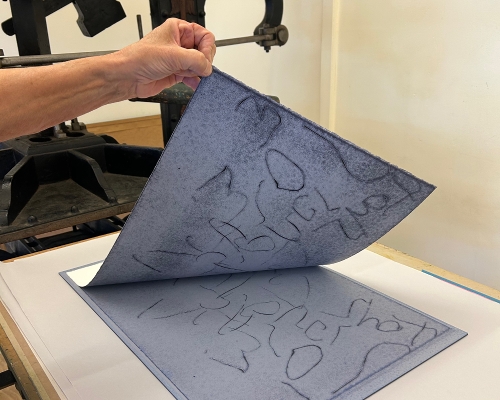

For a city of its size, Gimuy/ Cairns has a healthy number of exhibition spaces, including the venerable Cairns Art Gallery, the Tanks Art Centre and Court House Gallery, the latter both operated by the Regional Council. There is also NorthSite Contemporary Arts, a gallery, retail and studio- based organisation founded by local artists as Kick Arts in 1993, the year that Queensland Art Gallery (now QAGOMA) launched the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, putting the institution, and the state’s nascent contemporary art scene, on the global map. Like many centres, Gimuy/ Cairns lacks sufficient studio space, with the exception of the former Djumbunji Press, a purpose-built print studio in Edge Hill, which NorthSite has recently taken a long term lease on with plans to reenergise the region’s once dominant printmaking scene.

North of the Capertee Valley, on Dabee Country, is Combamolang, a long mountain with multiple peaks and outcrops. The mountain’s slopes form a dramatic escarpment above the flat land below where the silos of a factory stand out amid the bushland. Beside the factory is Kandos, the town built for the cement workers when the industry was established here in the early 20th century. It has a wide main street with civic buildings and shops under awnings, extending out into a grid of residential streets that end at the foothills of the mountain.

Since Kandos was established in 1914 it has developed its own distinct identity, drawing people to it first for its industry and, more recently, as a centre for regional arts. Following the closure of the cement works in 2011, the town has become a locus for place- based, socially engaged art practice. In the early 2010s Cementa festival founders—Ann Finnegan, Georgina Pollard and Alex Wisser—moved to Kandos, bringing their experience as arts workers and their enthusiasm for sustaining a contemporary art community. The first Cementa occurred in 2013, and the upcoming Cementa24 is the sixth time the festival has run, this time guest- curated by Daniel Mudie Cunningham and First Nations curator Jo Albany. It marks a new phase—with the festival coming into its second decade—with an established presence in the region and on the Australian arts calendar.

In December 2022, four staff at the Broken Hill City Art Gallery (BHCAG) and Museum resigned after a year- long public debate over art, local identity and heritage in one of Australia’s most iconic ‘outback’ towns.

I moved to Broken Hill in January 2021 to take up the role of Programs Officer, later employed as the Curator, at the Gallery. I often describe moving to Wilyakali Country as humbling. Having spent most of my life in the inner suburbs of Naarm/Melbourne, I quickly learnt that nothing is theoretical in a small community. Relationality is essential. In my first month, I was stopped by a local and asked if I was an ‘A-grader’. I would come to understand the subtext of this question, perhaps more of an accusation than genuine inquiry. A mining boom turn of phrase, if you were born and bred in Broken Hill, you were considered an A-grader; if you married in or lived in Broken Hill for many years, a B-grader; anyone else was a C-grader. Today, this persists with the more palatable notion of being ‘local’ or what’s known in Broken Hill as ‘from away’ (that could be Dublin, Dubbo, New York or simply the next town over).

I grew up in the regions. I still refer to myself as a country kid. I grew up close to Country on the Wotjobaluk- tended lands of Horsham, over three hours’ drive northwest of Melbourne. My ancestral homelands were slightly further north: the fresh-and-salt- water lakes known by my Wergaia and Wemba-Wemba ancestors.

In Horsham, our family felt like an anomaly. My Aboriginal father had died when we were young, my English mother remained in Australia to raise us, and she was an artist involved in the rich cultural life of our town. For me, and many others, the creative heart of regional communities was both life giving and life-saving.

Tough luck to the wood that becomes a violin.

– Arthur Rimbaud, letter to Paul Demeny, 15 May 1871

The picture which is looked to for an interpretation of nature is invaluable, but the picture which is taken as a substitute for nature, had better be burned…

– John Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1844

Like an enveloping atmosphere, ecology has become a dominant framework for contemporary art. In parallel, criticism has assumed the task of interpreting and re-interpreting art and its history for the ecological moment. Despite its near-imperialistic tendency to redefine the meaning of art works in ecological terms, the use of ‘ecology’ as a framework often precludes critical analysis rather than invites it. We are compelled to equate ‘ecological’ alongside terms like ‘life’ and ‘care’, with ‘good’, neatly bypassing both aesthetic and political judgment. Ecology is levelled to any lively, activated network, ignoring the dead, inorganic and artificial aspects of real ecologies. In the efflorescence of eco-art, the living overtakes the dead at the cost of art’s function...

To continue reading...

Lucienne Rickard’s Extinction Studies (2019–2023) was a long durational, live drawing project commissioned by Detached Cultural Organisation and staged in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s Link Foyer spanning four years and three months. Delivered in two iterations, the project focused on extinction as a key concern of the global ecological crisis and a phenomenon much talked about, but rarely witnessed at close range. Informed by links between the destructive impact of human activity within the Anthropocene and the ‘sixth’ mass extinction event, Rickard’s daily presence in the Museum framed extinction as a phenomenon to which we might bear witness in the here-and-now. Employing the double-edged strategy of drawing an extinct or endangered animal on a large sheet of paper and then erasing the image, Rickard’s project alluded to evolutionary cycles as viewers could witness, sometimes over months, the emergence of an anatomically accurate creature, only to watch it disappear in minutes under her eraser.

To continue reading...

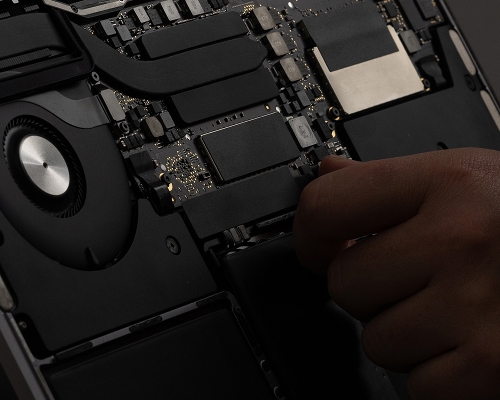

It’s 2am, and I am editing images on my MacBook Pro to include in this visual essay. I am using the Pomodoro method while I work, my iPhone keeping track of time. I am thinking about rare earth elements (or REEs, or rare earths) and their wide use in contemporary art, particularly media art, photography, video, film and animation. If life cannot be separated from art, then it is impossible to have an art practice in 2024 that does not depend on the mass-scale extraction of stolen Indigenous land and resources.

To continue reading...

2022 Tiyari, Tiwi season of hot and humid. We felt unsettled watching the news of Jikilaruwu Tiwi Island clan seniors taking South Korean Government to Seoul Central District court; a sip of solidarity beyond state borders to halt financing Santos and SK E&S Barossa Gas Project near Tiwi Islands. But the court dismissed the case after two months as foreign environmental rights are inaccessible to the Korean constitution. In scrutiny, ‘rights to clean air’ as basic rights is categorised under South Korean private law, which was a seeded sacrifice when the constitution was first drafted in the ‘60s after the Korean war—the beginning of economic boom and resource privatisation. This underlying legislative code of proprietary extractions has been reinventing “natural environment”, “resources” and “wealth” using becoming-Global-North colonial science, where the environmental law in Northern Australia is sprouted from these legislated Ponzi schemes.

To continue reading...

I have never seen a Gouldian finch “in the wild”, but over the past two years I have become familiar with its image on signage in Darwin streets and byways along with the words Save Lee Point. This typically shy, mostly silent and endangered bird is the brilliant icon of a grassroots movement to protect one of Darwin’s last remaining woodland corridors.

To continue reading...

, detail. Image courtesy and © Badger Bates_card.jpg)

- Fotografer Ariyanto Nugroho_card.jpg)

_card.jpg)

_card_Crop.jpg)

_Card.jpg)

Bisma (2023)_Card.jpg)