The “painting is dead” metanarrative of the previous half century, intended to end a certain universalism, instead ensured its immortality. Narrative + Painting takes the end-of-painting myth by the horns and continues Artlink’s model of media-specific thematic issues. However, it is the first to focus explicitly on a medium that is perfectly able to take care of itself. So why celebrate a tradition that historically “helps itself” to authority? Why highlight the most anachronistic of mediums in an age of inter/trans media?

Because painting remains a critical narrative tool for our posttruth times. Fifteen years ago, art historian Helen Hughes claimed that contemporary art biennials typically ‘touted an amorphous, fragmented and open-ended rhetoric of dialogical and ephemeral art to reflect the sense of uncertainty and mistrust pervading our planet.’[1] Within a context that apparently leaves little breathing room for painting, the medium has continued to hold ground as a poetic space for our imaginative interpretations, whatever the artists’ and curators’ intentions.

If painting’s generals are exhausted, its particulars—art’s foot soldiers, the writers—are fresh and eager to wrestle out new interpretations, sharpen our attention, propose uncertain truths and reveal playful pictorial devices. In commissioning Narrative + Painting I matched some writers with painters, and invited others to choose a painting they felt had good narrative bones to pick over. The exception is Andrew Browne’s essay on Diena Georgetti’s Surgeon’s Playlist/Wilding (2025), which comes courtesy of Neon Parc, commissioned for Art Basel Hong Kong. Georgetti is a painter who grants modernist icons their best side, obliquely.

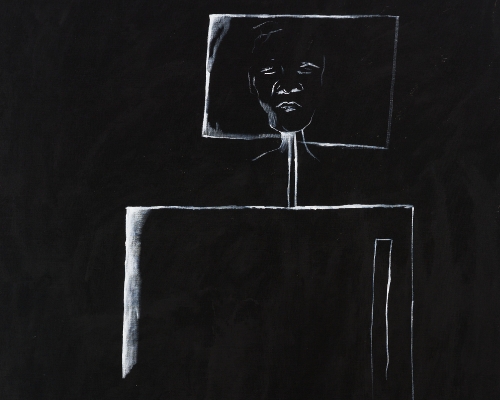

The figure looms large throughout this issue, led by Djon Mundine’s site-specific body marks, a theatrical and universal origin-story for painting. In more formal arthistorical attire, Rex Butler muses on stories and fictions in paintings by way of figuration, which also finds an unlikely presence in Nur Shkembi’s essay on Khaled Sabsabi’s figurative portraiture, partly abstracted, the artist says, to make them ‘accessible, familiar and universal’. In hindsight, Creative Australia’s recent and divisive “Venice Decision” (to cancel Sabsabi as the nation’s artist-representative at Venice in 2026) begs the question: had he painted certain controversial subjects eighteen years ago, instead of working with film and photography, would we have witnessed such a misapprehension and unravelling of art’s ambiguous fluency?

Speculating on painting’s inherent ambiguity while reading Cameron Hurst’s piece on Berlin-based Billy Coulthurst’s kitsch marsupial portraits, I wondered if the Australian government might send paintings of koalas to the next Venice Biennale? After all, cute fluffy icons are easily digestible if taken at face value. For the record, its twenty-six years since a painter was selected for the national pavilion: Howard Arkley’s The home show, foreshadowing the major housing crisis of today.

Public holdings give up some artful narratives: Daniel Mudie Cunningham uncovers the Illawarra’s lost surrealist Joan Meats by way of Wollongong Art Gallery’s collection, and Belinda Howden brings a burlesque flourish to a baroque hang at the Art Gallery of South Australia. My contribution is prompted by a recent gift to AGSA’s collection, Two Laws One Big Spirit, painted by Peter Adsett and Rusty Peters (Dirrji) a quarter-century ago. Also in Adelaide, drawing on the Flinders University Museum of Art collection, Ali Gumillya Baker and Fiona Salmon write on Sandra Saunders’ paintings on Australian government policy and historical reverberations which form the backbone of their art-led teaching program.

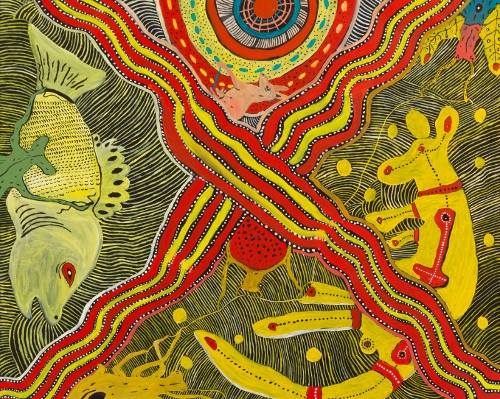

On related historical themes, Tristen Harwood spins together the expressive paintings of two East Kimberley artists: John Prince Siddon’s probing contemporary mashups of political, spiritual, ecological and global concerns, and Mervyn Street’s Stolen Wages paintings documenting Western Australia’s long exploitation of Aboriginal pastoral workers. More revelations of indentured labour are portrayed in Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s kūlī / khulā (2024), commissioned for the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial and examined in detail by writer Sophia Cai.

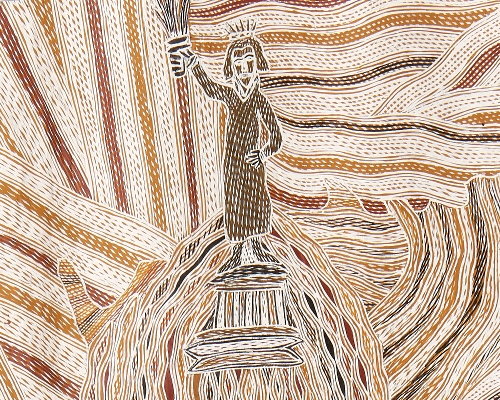

Looking north, Indonesian contemporary art specialist Elly Kent surveys the multicultural and art historical borrowings in Zico Albaiquni’s vivid, montage-like canvases and Virginia-based scholar Henry Skerritt traces the movements of Djambawa Marawili’s Journey to America (2019). As Skerritt argues, Djambawa’s elaborate clan designs, drawn from Yolŋu bark painting traditions, are powerful aesthetic and material evidence of Yolŋu political engagement both locally and internationally.

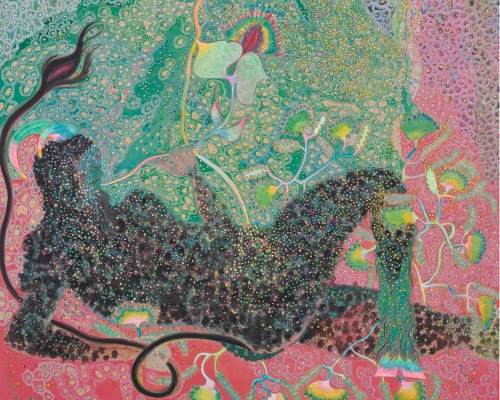

Painting remains one of the most immediate—but also one of the slowest—ways of showing and telling us stuff about the world, and as a panacea for the multitude of contemporary evils, painting bears a heavy burden. Studio processes, archival research methods and collaborative exhibition models surface in essays on South Australian artists by Michael Newall, Riley O’Keeffe and Eleanor Scicchitano. Among the painters featured is Deidre But-Husaim, whose deadly Angel’s trumpet on our cover exhibited in Adelaide’s Neoteric exhibition in 2022. More ominous is her new work in progress shown on page 85, one of two paintings of outback, tray-back, work trucks reproduced in Narrative + Painting. I did not see that coming.

Footnotes

- ^ "Before and After Science: 2010 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art”, [review], Artlink 30:2, 2010

_card.jpg)