A tempered but stubborn nationalism haunts the contemporary biennale, appearing most paradigmatically in Venice’s pavilion format. Its seductions are less obvious in the latest edition of the Biennale of Sydney, curated by Cosmin Costinaș and Inti Guerrero, which has sought to decentre North Atlantic discourse through an emphasis on a multiplicity of perspectives (Ten Thousand) unfolding within a shared planetary system (Suns). But, even when placed within the ‘global’ schema of the biennale, nation and nationality are convenient heuristics, appended to names in placards and media releases.

This faith in the nation is mirrored in the undertones of Australian foreign policy lingo over the past three decades—forever anxious to articulate its position in a region it has characterised as an arc of instability, in which Indonesia, under the threat of ‘Balkanisation’, formed an unstable epicentre. But what hegemonies are concealed by a fixation on colonial cartographies, and their potential undoing? How might a close reading of the ‘Indonesian’ representation in Ten Thousand Suns draw attention to the fictive and uneven qualities of the national imaginary, even if the ghost of the nation cannot be exorcised?

As Indonesia crowns its new capital in Borneo, Nusantara—a vision of archipelagic unity conceived from the vantage point of Java—it is striking that the curation explores the perimeters of Javanese cultural and geopolitical power. On the lower level of UNSW Galleries, the walls of an entire room have been painted over with red, stylised images of death and protest, documenting Papuan resistance to militarised Indonesian administration in Western New Guinea. Udeido Collective’s The Koreri Transformation (2024) accesses both the revolutionary visual language of the mural and concepts drawn from Biak folklore: Koreri is invoked in the sense of a promised land or eternal order, inextricably entwined with expressions of Papuan political aspirations under Dutch and Japanese colonial administration and Indonesian annexation. Through the physical manifestation of a utopian future, Udeido creates a space for healing, and for centring the Papuan cause.

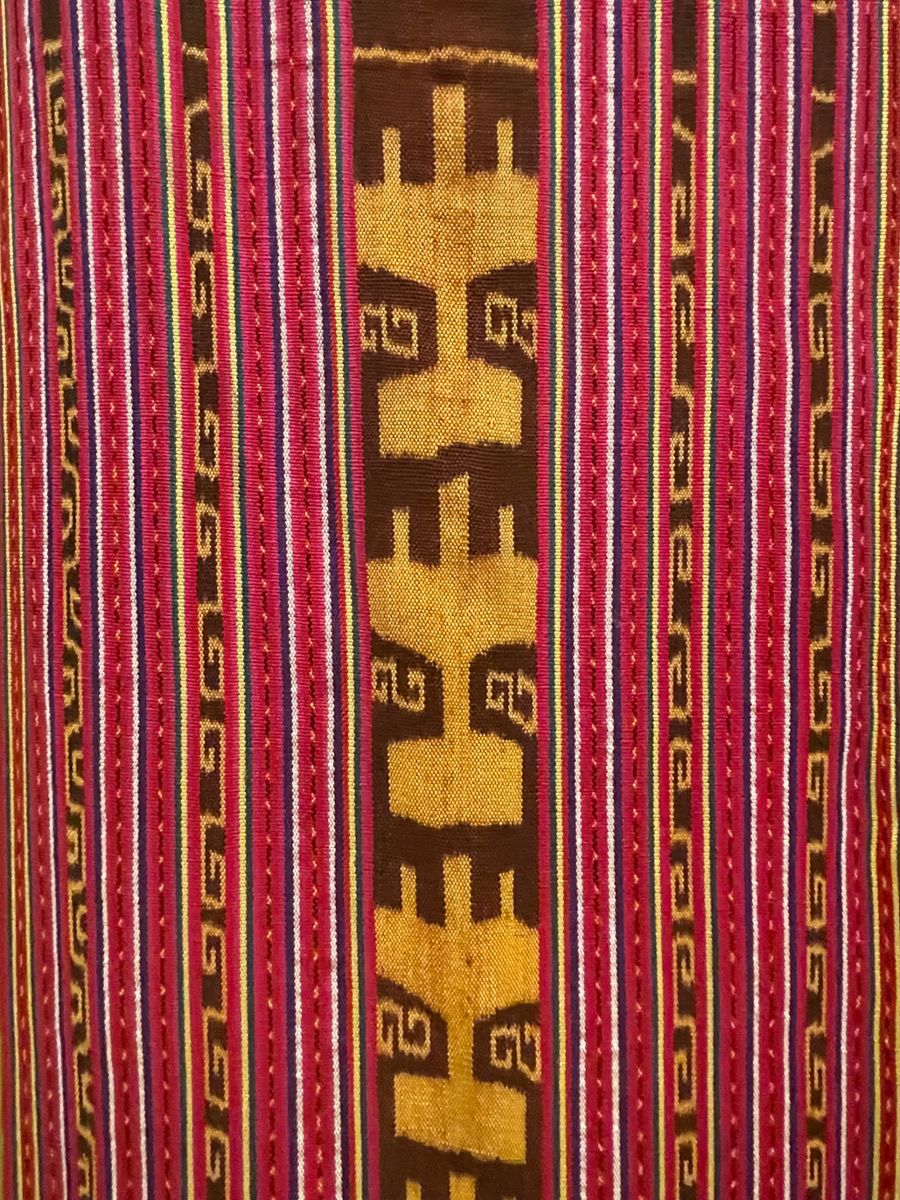

But resistance emerges in different cadences. At the AGNSW, a Tais Mane (2022)—men’s ceremonial cloth—hangs in a room with works recounting the Second World War. Magdalena Meak, an artist from West Timor, in Indonesia’s southernmost province, has been weaving tais for nearly forty years. The presentation of textile, often overlooked as domestic craft work, considers the material as a carrier of Indigenous knowledge and collective women’s labour, sustained, in Timor, throughout a history of colonial occupation. Meak documents the forms of fighter planes (ro) during the Japanese invasion in handwoven motifs, dyed the colours of the Timorese flag. The registration of a symbol of modern warfare in ikat textile suggests a kind of defiance; Meak presents a material testimony to the role of Timorese women as producers of cultural knowledge which survives war and conquest.

This troubling of the borders of the nation-state is accompanied by an intrigue for historical zones of contact as alternative configurations which predate European colonialism. Dhopiya Yunupiŋu’s bark painting, Yolnu showing the first Makassans the land (2022), terracotta ceramic Galiku (2023), and American Candice Lin’s untitled, spinning installation of manganese-gold-glazed ceramics surrounded by a black moat, all reference a history of trade of trepang (sea cucumber) connecting Makassan merchants and Indigenous peoples of the northeast Arnhem Land in the 18th century.

With a similar eye for spaces of cultural exchange, Berlin-based Singaporean artist, Choy Ka Fai, mediates our perceptions of popular contemporary Javanese cultural forms through a hybrid documentary-music-video, highlighting processes of (sonic) fracture, absorption and generation. In Exodus (2024), Choy examines the parallel development of Indorock in Europe and Dolalak in Java and stages their convergence: three members of the TikTok viral Dewi Arum dance group perform in glamorous cosplay of Dutch military uniforms to remixes of songs by Dutch-Indonesian band, the Tielman Brothers. Fusing genres and sounds spanning Javanese trance, dangdut (Indonesian pop), kroncong, Islamic poetry, and West German Rock ‘n’ Roll, Choy speculatively retraces the eclectic transcultural influences in contemporary artforms which have emerged from the colonial encounter.

These pronunciations against the homogeneity of nation also conspire against the prejudices of the art historical canon. At the Chau Chak Wing Museum, Citra Sasmita’s Timur Merah Project X: Bedtime Story (2023) and Project IV: Tales of Nowhere (2020), reference the stylistic tropes of a painting tradition associated with Kamasan village in East Bali, in which narratives and compositions are typically passed down through male lineages. Contesting the problematic location of women as objects rather than agents within the Indonesian art canon, Sasmita borrows the visual iconography of Kamasan temple frescos and ceiling paintings to figure women from Hindu epics and Javanese stories as the central characters of her work. It is a reinterpretation which also dislodges long-held ethnographic perceptions of Balinese art as craft that have distanced the ‘tourist’ island from Java’s contemporary art centres.

There are resonances in the paintings of the late I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih (Murni), who trained in Bali’s Pengosekan style of painting. Now a well-recognised (and well-collected) figure, Murni’s work is often read biographically, or as part of a commentary on the repressive climate of New Order Indonesia. Perhaps because of this, there is something untaxing about Murni’s paintings seen in a biennale context, which can at times privilege form over discourse. From afar, her canvases (at AGNSW) appear as flat expanses of colour, which jostle against each other. But a longer look reveals modulating organic forms which are at once erotic, vulnerable and grotesque. In Jalan Santai (undated), a ring that is a touch too tight, causes the flesh of a digit to swell around the band; a swollen pink belly almost touches the frame in Hayalan 18 mei (undated); and a phallic handphone is gripped tightly, an index finger pointed to its ‘eye’, in Belum bisa lepas (2003). Rejecting the social conventions of Balinese art, Murni’s practice is as much a celebration of pleasure and sensuality as an observation of pain and repression.

.jpg)

The act of reading these works together across the Biennale venues makes visible the political configuration of the Indonesian nation, its violent birth, and its persisting territorial anxieties. In the same stride, it seeks to reveal the regimes of power and capital which overlap and structure the multifarious archipelago. And although this is a strategic grouping, the observations which emerge bear relevance to the Biennale’s wider curation. As contemporaneous imaginings occurring across multiple locales are staged together, works such as those by Udeido, Meak, Sasmita and Murni bear witness to movements, collectivities, and viewpoints which have preceded, survived, and still interrupt those uneven configurations of power.