_card.jpg)

In the Australian imagination, Bundanon–‘deep valley’ in Dharawal–is deeply connected with Arthur Boyd and the Boyd’s dynastic legacy: the 1993 bequest of 1000 hectares of bushland, farmland, two homesteads and an art collection valued at $47 million. On the face of it, Bundanon is a regional arts and cultural centre, but unless one counts Canberra as a regional city, it’s the only National Collecting Institution in regional Australia. This means it is the only regional museum with access to NCI federal funds. The government’s 2023 national cultural policy ‘Revive’ also smiled at Bundanon, significantly growing the Boyd vision–and raising public expectations.[1]

Launched in 2022, Bundanon’s new Art Museum and Bridge for Creative Learning is located at Riversdale, straddling a gully and the crest of a north-east facing slope above the Bangli / Shoalhaven River; it’s an environmentally ambitious, award-winning jewel designed by Kerstin Thompson Architects. The site was purchased by the Boyds in 1973, and a colonial-style building (designed by Andre Pobreski) was constructed near the original house. The Boyds took up residence there–when not in Europe or the UK–in 1975.

A few years later, the Boyds bought the nearby Bundanon site, a 20-minute, forest-road-drive from Riversdale. Here, adjacent to the original Bundanon Homestead, is Arthur’s studio and a complex of artist-in-residence studios. In mid-2023, the restored Homestead and studio reopened to the public. These dual achievements have been widely celebrated and promoted, and the Bundanon Trust’s Board and CEO Rachel Kent are metaphorically beaming, as returning loyalists and first-time visitors patronise the estate. How many of them are seeking Destination Boyd? And how difficult is ‘activating’ such a space in keeping with Boyd’s diffident wish ‘for people to come together and talk’?

In Wilder Times: Arthur Boyd and the mid 1980s landscape, ‘the master’ is present in all his oily, gestural glory. The exhibition hinges on fourteen of Boyd’s paintings made at Bundanon in 1984 for the Arts Centre Melbourne Commission, installed there for the past forty years. A major refurbishment of the theatre has allowed the works’ repatriation ‘home’ for the first time. These are among Boyd’s quintessential Shoalhaven landscapes—the dramatic skyline, rocky slopes and Pulpit Rock reflected in the river’s surface over day and night, repeated in the paintings’ reflection in the polished concrete floor. In Melbourne, the paintings compete with the traffic of passing audiences and busy ‘80s-style interiors. In the Bundanon Art Museum, shielded by its quiet country setting, they look corporate and yet (befittingly) theatrical. The ostensible motif is straightforward, but the horizontal-Rorschach presented ink-blot tests I found difficult to pass up: a pink nude (Shoalhaven River Bank–Dawn), a phallus (Dark Cloud–Shoalhaven River), the crowning moment in childbirth (Shoalhaven River and Black Swan) and the ominous head of a crocodile, semi-submerged (Early Light–Pulpit Rock).

Before giving too much away as an essentialist viewer inducted into Indigenous anthropomorphic narratives of place (rock, bird, lovers, star), I wonder if this is my way of looking past the images which are so typecast, and so commodified. (“Oh, Boyd’s potboilers?”, someone rolled their eyes.) The texts developed for the show present the series as emblems of Boyd’s love of place, and care for the natural environment. In over-psychoanalysing the doubled-landscapes—far removed from the orchestrated Rorschach methods of Ben Quilty (or Andy Warhol for that matter)—it’s easy to overlook the nuances in paint handling and the rich continuity of practice seen over and over. Or to dismiss the lifelong investment in the exercise of gestural expression, which Boyd once described as similar to a tennis player’s craft, more wrist than mind.[2] These are unpeopled landscapes, but Boyd was emphatically a painter of allegory and myth, and at the time of the Melbourne Arts Centre commission, the reflection compositions were echoed in his Narcissus (1984) suite of etchings and aquatint (which are not included in Wilder Times).

As imagery now, forty years after their execution, Boyd’s celebrations of Australia’s bushy beauty, without erasing its colonial melancholy, carry the full weight of the landscape tradition in a postcolonial, post-1988, post-Apology, post-Referendum context. In 1984, Uluru was Ayers Rock and the world’s ‘oldest living culture’, Aboriginal Australia, was clocked at a mere 40,000 years. If anyone could be accused of failing to acknowledge the sins of colonisation, it’s not Boyd. Love, Marriage and Death of a Half Caste (1957-59)–or his Bride series as it’s known–predates the 1967 referendum by a decade, and his 1988 Venice Biennale Australian Scapegoat series pulled no punches in attacking colonialism and nationalism. Only in de-historicising Boyd’s work is it possible to misread his intentions, and at first glance I was blinded by my own generational prejudices, not seeing the subject for the motif.

Along three long walls the fourteen paintings present a full-sweep and comparative view of the pursuit of a subject ‘over and over.’ In Wilder Times the sequence departs from the State Theatre’s arrangement, re-mixed for aesthetic balance, starting with the nocturne Starry night–Shoalhaven River, the southern cross constellation apparent. However, any theological associations with the Christian Cross and its fourteen Stations, a recurrent theme for artists, are misplaced here: Boyd was originally commissioned to paint seven canvases of matching scale. Another artist stumbled, and Boyd, no stranger to assembly line production, stepped up to deliver double. Worked up from on-site sketches, there’s a loose plein-air sketchy, breeziness evident in works such as White Cloud on Shoalhaven River and Black Cockatoo–Shoalhaven River.

On the fourth wall, the four-panelled Pulpit Rock, Bathers and Muzzled Dog (1985) poses a different question to the 'wild' Shoalhaven works. Monstrous, red-fleshed figures, water sports enthusiasts with flipper-feet and bathing caps, frolic in a perversion of Charles Meere’s Australian Beach Pattern (1940) and illustrate Boyd’s despair at the leisure class, the pleasure seekers (read colonialism) spoiling the pristine Shoalhaven environment with its pulpit totem, disrupting the tranquillity in ignorant bliss:

…with Narcissism, there’s this sheer lack of imagination, but with the hedonism idea, it’s not so much a lack of imagination, it’s just that there’s no awareness.[3]

Whether Boyd’s reproach is self-aware or more a finger-pointing moralism, the work yields to ambivalence and echoes contemporary concerns. Either way, Pulpit Rock, Bathers and Muzzled Dog offers the more socially charged face of Boyd’s body of work and specifically his deep-running and practical environmentalism, work that started in the 1970s with Sidney Nolan’s involvement, and remains a key focus in the current Bundanon plan working alongside First Nations experts.

.jpg)

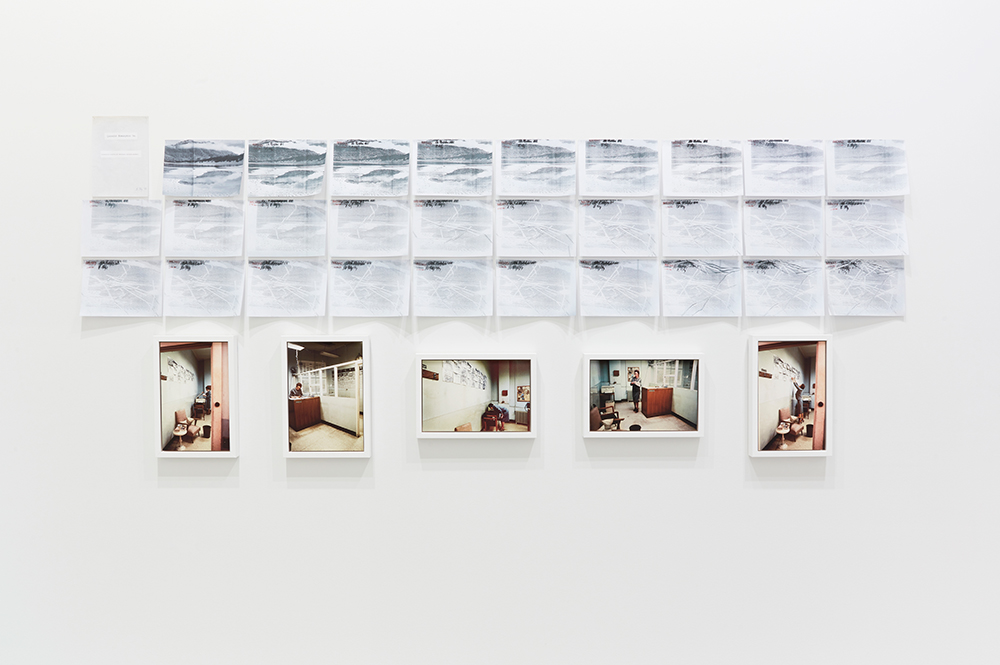

For Wilder Times curator Sophie O’Brien, 1984 functions as a key for a selection of works by other artists that capture the broader zeitgeist. These are displayed in the adjoining three galleries with the ‘Beyond Boyd’ subtext. (A tally of creative tributes to the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four would land in the millions). The catalogue essay doesn’t give much away as to O’Brien’s choices beyond acknowledging the pluralism of the time and the political currents fuelling artistic practice: anti-Uranium mining and nuclear disarmament, feminism and sexuality, environmental issues and the rise of Aboriginal art and its political import, amplified in the lead-up to the 1988 Bicentenary. Four remastered films add important historical context to Wilder Times, with Midnight Oil: 1984 (2018) screening on the opening weekend. Some other non-painting inclusions that resonate are Helen Grace’s experimental, feminist film Serious Undertakings (1983), and Bonita Ely’s Controlled Atmosphere (1983)—an archival documentation of Ely’s performance during the (successful) national protests against the proposed Franklin River dam in Tasmania.

In essence, the ‘Beyond Boyd’ rooms are a version of the now standard curatorial convention (Gauguin’s World and the SaVĀge K'lub 'coupled' at the NGA is a current exemple) to counteract the main act: in this case the broad-brush, Boyd brand of twentieth century Australian mythmaking, with its heroic market share. In 1984, the polemical painter Juan Davila (not showing in Wilder Times, go figure) speaking at the Adelaide Festival offered his opinion on such an approach:

The curatorial scene in Australia has often placed these two painting positions side by side, under the eclectic principle, having the effect of creating a confusion between the gestural painting and the semiotic and critically orientated painting, cancelling out the potential for discussion.[4]

The first of these secondary gallery spaces contains the more-or-less-explicit Aboriginal Indigenous cross-cultural influences on Australian artists, which in 1984 was not as institutionally reconciled as it looks here. Tim Johnson’s Papunya (1983-85) from his series of paintings of the Papunya Tula artists points to one of the long relational and poetic engagements, but it is disappointing that no distinctive mid-1980s Papunya paintings (typically large-scale, symmetrical, neat and balanced) are included; the movement feels insufficiently represented in Timmy Payangu Tjapangati’s small Snake dreaming (1984).

Hanging in the optimum position of (visual) power, Imants Tillers’ large scale Pataphysical Man (1984) owns the space, but even Tillers the great appropriator, has only drawn lightly from Boyd.[5] Adjacent large-scale photographs of the Kimberley by Richard Woldendorp opposite paintings by Rover Joolama Thomas adds indexical gravitas while neatly signalling the culturally distinct modes of seeing and showing the land, specifically northern Western Australia and Gija Country.

In the space dedicated to 1980s abstraction (soon to become the Boyd Collection Gallery granting year-round access to the Bundanon Art Collection), Howard Taylor, Brian Blanchflower and the little-known Mac Betts nod further to the curator’s Western Australian interests. Blanchflower’s dark metaphysical hymn, Canopy 1 (Long Man’s View) (1982-85), John Peart’s eucalyptus-esque Naples Green (1985) and Liz Coates subtly hatched minimalism offer a contemplative space and make the quiet argument for an alternative spiritualism of place that is less pictorial.

Wilder Times represents a specific public interest in seeing Boyd’s art, and likely these reflect the demographic of certain patrons. This is the eighth season in the revitalised Bundanon program, which is juggling the desires of multiple audiences. First Nations are naturally a high priority and the summer season opening in November, Bagan Bariwariganya: echoes of Country, is a celebratory case in point. Previous seasons (exhibitions and public programs) bear this out too–the long view of programming, like a thematic magazine, requires a broad rhythm.

As Bundanon Trust's Chair Sam Edwards noted in a fireside aside during the opening weekend, the optics of public spending on such a cultural asset is often seen in stark contrast to the limited resourcing of the public education and affordable housing at the local level: the old bush/city misinformation and antimony is played out in regional class structures. While the crown investment of Bundanon has the relative means to deliver in a rural setting, the Trust has to serve many masters, past and present. Being all things to all people, in line with Boyd’s often repeated mantra that Bundanon must be accessible to everyone, is no easy task. The best thing you can do is go and visit whichever regional galleries are within range, big or small. You’re the one they’re really servicing.

Footnotes

- ^ See the Bundanon Trust Annual Report, 2022-2023. Notably, staffing increased from 36 to 50 from July 2023.

- ^ Arthur Boyd, interview with Richard Haese 1974, cited in Barry Pearce, Arthur Boyd Retrospective, (Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney: 1993), 25

- ^ Arthur Boyd in Robert Walker, Painters in the Australian landscape, (Sydney: Hale and Ironmonger, 1988), 24. Cited in Pearce, 29.

- ^ “What’s Happening to Painting?” symposium, 16 March 1984 [speakers: Peter Tyndall, Juan Davila, Vivienne Shark Lewitt, Margaret Plant with Chair Ron Radford and Terry Smith ‘from the floor’], Artlink (June-July 1984), 4: 2&3, 43.

- ^ Tillers references Boyd in at least two works within his oeuvre: St Francis Taking the Rosary (1983) from Boyd’s 1970 lithograph of the same title, and Erased Portrait of Murray Bail (1985). In the latter work, Boyd’s Interior with Black Rabbit (1973) was overpainted with imagery from Ian Fairweather’s Chi-tien Stands on His Head, (1964).