As the 2024 South Australian Living Artist (SALA) Festival comes to a close, it is timely to reflect on its legacy. A fixture in the ‘festival state's’ calendar, the expansive visual arts program runs throughout August, taking over public, private and commercial galleries, artist-run spaces, side streets and shop windows, cafes, hairdressers, and the more unexpected venues of people’s homes or occasional front lawns. Once the exhibitions and events are packed down, SALA endures in the festival’s branded monograph. The SALA publication, a state-government funded offering dedicated to an individual South Australian artist’s (mid-)career, has been running alongside the annual festival since 1999. As a continuing chronology of visual arts publishing, it is a rare model within Australia.

Beyond vanity projects or glossy coffee table art books, neither of which typically attract public funding, gallery-published monographs are the more standard path for artists to garner the same depth of critical attention and cataloguing of their practice. These institutional monographs often accompany major solo survey exhibitions, naturally towards an artist’s later years, canvassing an ‘established’ career. And, as the 2022 Countess Report reiterates, women artists remain disproportionately underrepresented, accounting for just 39% of solo shows at state galleries, nationwide.[1] Good luck with those mid-career doldrums. Another pathway, perhaps more morbidly, is when an artist dies. Like any good book, an ending does help form a cohesive narrative arc, and therefore streamlines the messier canonisation of an artist with more thinking and making to come. Either way, both options take a retrospective rather than speculative view.

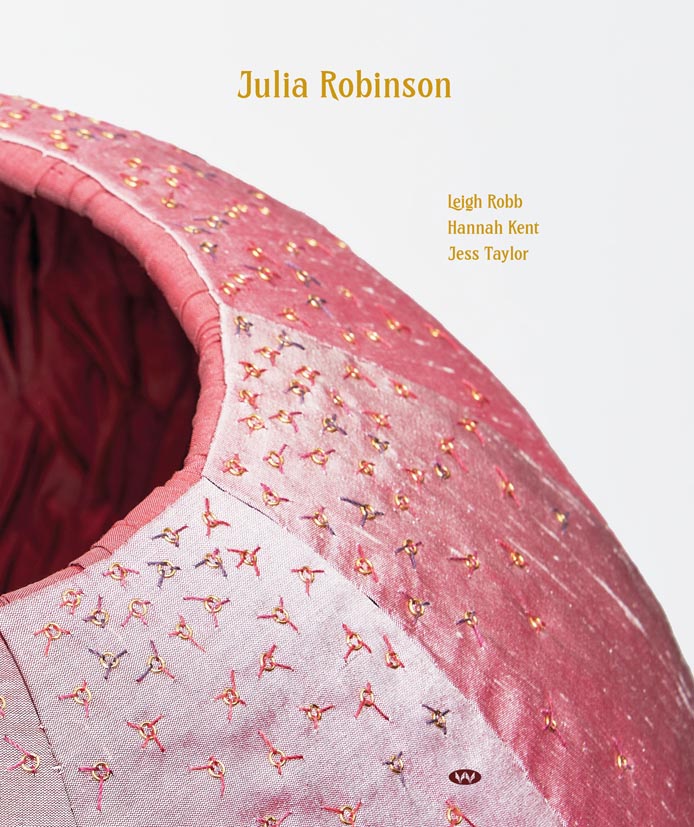

Julia Robinson is the feature artist of SALA this year, and subject of the monograph published by Wakefield Press. At a hefty 176 pages, Julia Robinson bridges just over two decades of the artist’s exquisitely detailed textile practice and perverse sculptural sensibility. It weaves together the curatorial insights of Leigh Robb, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), poetic and fictional interjections by award-winning novelist Hannah Kent and canny visual analysis by emerging South Australian artist and fellow horror enthusiast Jess Taylor. The mix of authors speaks to Robinson’s artistic interests but also one of the monograph’s remits–to facilitate intergenerational/inter-career mentoring between authors. The SALA publication is designed for artists and writers alike. It is also interesting to note that, while the publication sits among a suite of promotions during the festival’s activities–the SALA feature artist is the subject of podcasts, interviews, artist talks and public programming–the selection process for the SALA feature artist is determined by the monograph.

Robinson has had a string of knockout shows over the last few years. The Beckoning Blade was a major solo exhibition at Hugo Michell Gallery in 2022, a crescendo (so far) in uniting Robinson’s exacting techniques with her favoured subjects–folklore, folk horror, fairytales, ritualism, rites of passage, death, sex, rebirth. Robin Hardy’s 1973 film The Wicker Man provided fertile ground as inspiration for Robinson on this occasion, with the body of work featuring twenty sculptures based on repurposed agricultural equipment. There is an emphasis on ‘body’, here, as the clothed scythes and sickles, and bloodless figurative intonations of The Beckoning Blade were not only the subject of the series itself, but also reflect Robinson’s approach to thinking in constellations of objects. From intricate and precise hand smocking to dip-dyed linen ‘tunics’ in resonant colours–such as the bog brown to grass green capillary-effect of The Raker of Mud (2022) or bile yellow and plum-stained radial work Sunspurge (2021)–beneath every careful, thoroughly controlled sculptural decision flows a palpable undercurrent of violence and down-in-the-mud despair.

The Beckoning Blade was preceded by a series of nine sculptures made for The National 2019: New Australian Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, and Beatrice (2019-20), produced for AGSA’s 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres, staged at the Museum of Economic Botany in the Adelaide Botanic Garden. Beatrice is an outlier in some ways because, despite being a writhing installation of many tentacled limbs, the work was conceptualised as a singular object. Across both bodies of work, Robinson worked with shot silk using a decorative Tudor and Elizabethan slashing technique. And, both carved space decisively: precise barbs and needle-like thorns split a suite of sumptuous fruits and dressed gourds in The National, and Beatrice possessed the uncanny ability to lure you in.

I’ve lost the original source to time now, but I once read that the slashing technique, where a top layer of fabric is carefully incised and through which a layer below is pulled and puckered, was a fashion designed to simulate the cut of the sword in battle. A lavish technique given it requires twice as much material, it was primarily worn by royalty in the absence of doing any fighting themselves. Naturally, their garments should remain clean of mud. Whether it’s accurate or not, the mythology serves Robinson’s material trickery equally well. Her singular, and downright commendable, dedication to historic techniques and the sub-genre of folk horror could easily be misrepresented as niche; what does feudal serfdom tell us about today’s world? (Actually, quite a lot.) But as Robb skilfully illuminates in Julia Robinson, across each body of work we witness an evolution of ideas and material transmogrifications. It is as if Robinson were writing chapters of an anthology or scripting scenes in a film (and Robb moving through rooms of a gallery), where grand themes of patriarchy and power, class antagonisms, the perils of superstition, and the cautionary tales of groupthink or religious indoctrination are materialised (see the fiery fate of poor Sergeant Howie in The Wicker Man). Those universal human inevitabilities of growth, death and decay are played out; even social status can’t protect you from ending up in the ground. Certainly, by the time Robinson manifested The Beckoning Blade, the glut of material delicacies previously on offer–like the hybrid botanical specimen that was Beatrice and the cursed fruit of The National–had become over-ripe. Fallen from the tree and ploughed into the ground, they were now part of the fallow.

For Split by the Spade, Robinson has stayed in the fields. Curated by Andrew Purvis, Robinson’s solo exhibition at Adelaide Central Gallery launched the SALA publication, concurrent to a selection of works on display at Hugo Michell Gallery and a collection intervention at AGSA, Julia Robinson: Sculptural storytelling. Robinson’s strict figuration is not necessarily looser in Split by the Spade, but rather left to ferment. Her material decisiveness, on the other hand, remains evergreen with her experiments using bleach, which first appeared in Robinson's AGSA Studio takeover as part of the 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart, now more fully explored as a painterly surface treatment. As Robb states, Robinson initially trained as a painter.[2]

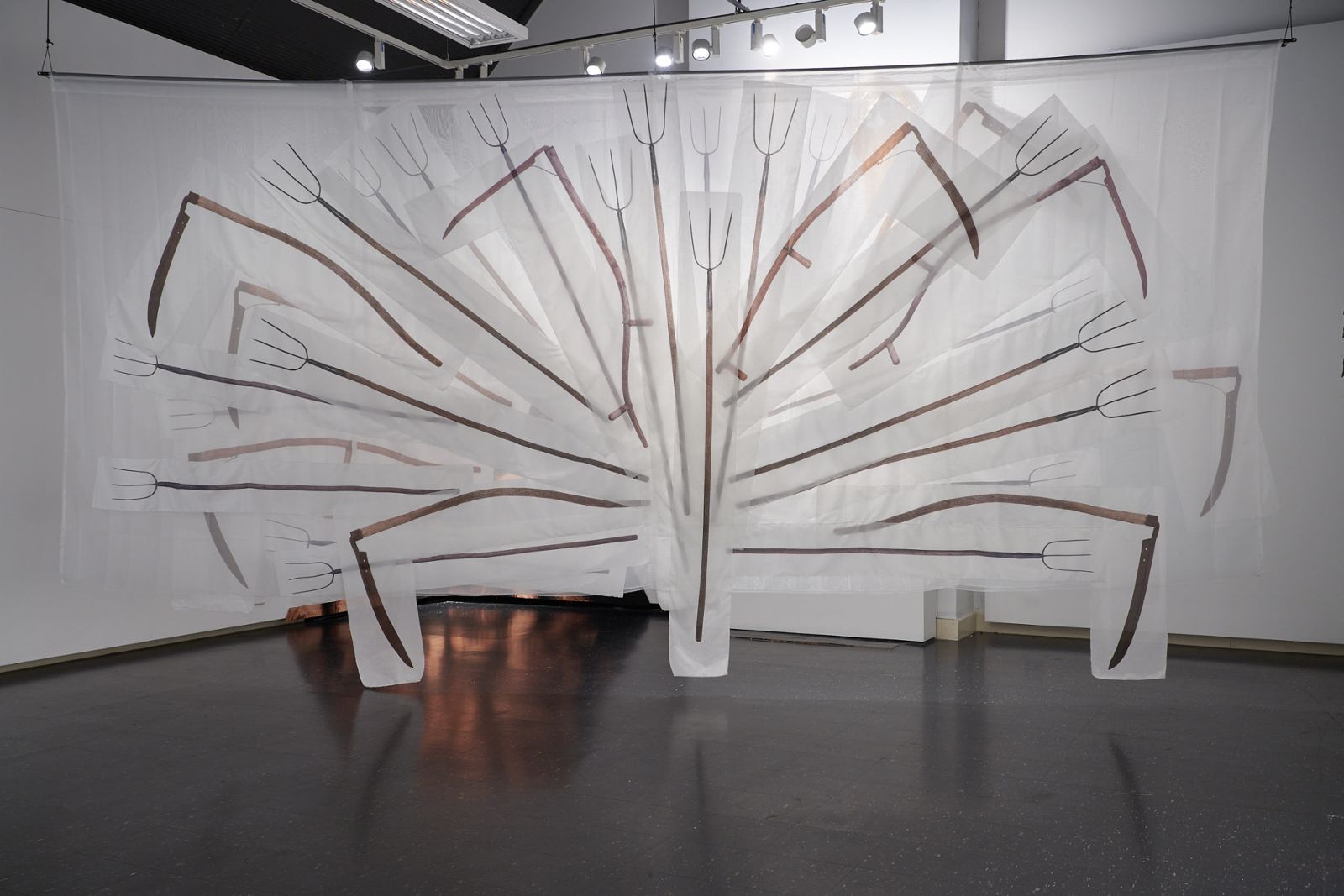

Split by the Spade is conceptually and spatially framed as an agricultural scene–think the back-breaking peasant life of Jean François Millet’s 1857 oil painting The Gleaners. A suite of five rusted wheels in various states of textile dress, shadowed by discs of brown oxide rubbed directly onto the wall, together form a seasonal arc that climaxes with the high summer/high noon of It watches with a yellow eye (2024). These ‘suns’ look across the scene, casting their line of sight over the large-scale diagonal installation Along the shuddering branches (2024)–a sheer veil of printed agricultural tools fanned out in a kind of anti-tree-of-life formation. Despite its translucency, the work spatially dominates. To answer my earlier question on the enduring relevance of Robinson’s subjects, the photographic literalism of Along the shuddering branches–Robinson's explicit rendering of pitchforks and scythes–draws a through line from the Renaissance capitalism of The Gleaners to the 1970s folk aesthetic of the Wicker Man, to the increasing Charlottesville ‘pitchfork and tiki torches’ mob mentality of contemporary (algorithmic) tribalism.

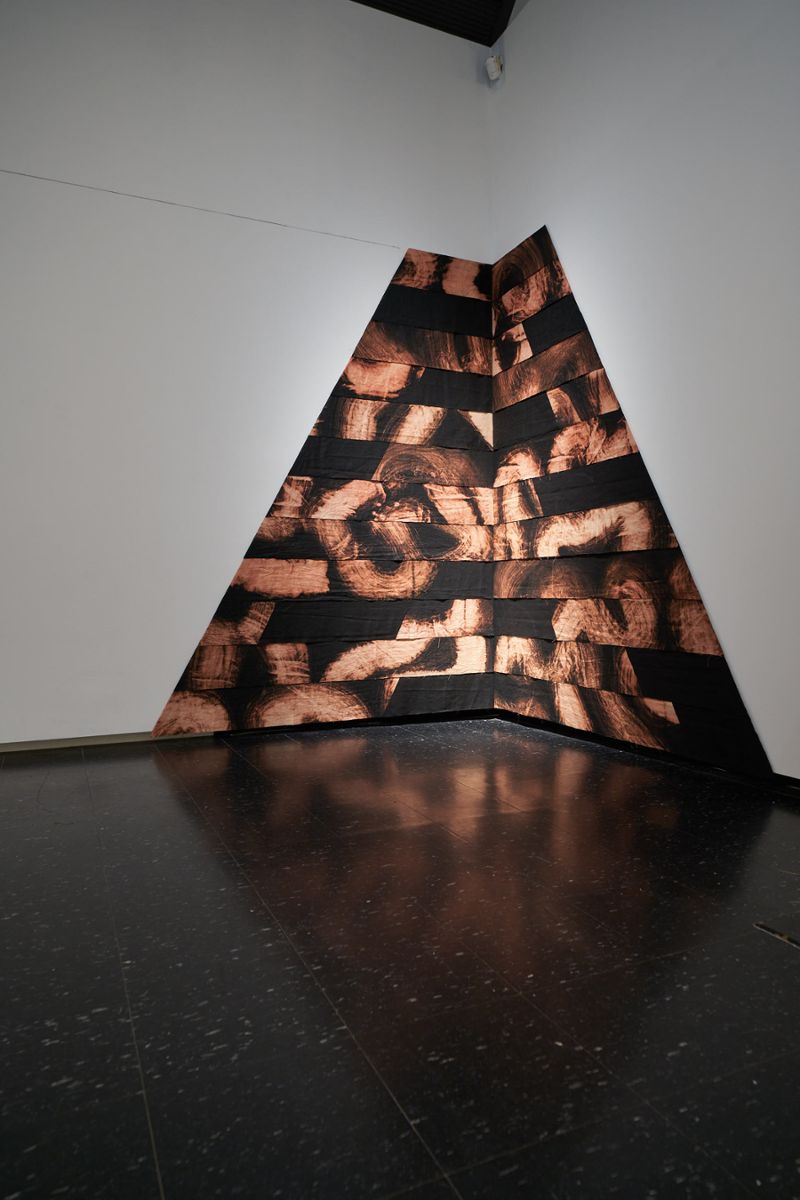

Robinson’s foray into the photographic image as object certainly offers another forking path for material investigation. However, it is her painterly use of bleach, particularly in the evocative wall-to-corner installation Beneath old patterns (2024), that offers something more transfixing, more fomenting. For Beneath old patterns, a barely-there oxide grid appears incised, or perhaps burnt, directly into the gallery wall–like a cast spell. The grid premeditates a single line traced to the corner, where it meets with an earthy geometry of rigorous and sweeping bleach strokes. This stratum of exhumed material taps into that familiar seething of The Beckoning Blade: decomposition, decay, the tragic indifference of life, a cycle of growth and erasure. The whole installation operates like a spatial hex.

In Julia Robinson, Robb unites the artist’s biography with the borrowed cultural power and figuration of the witch. Manningtree, a small parish of Essex, in England, was the hometown of Robinson’s paternal grandparents, and famously the site of the 1645 Manningtree Witch Trials. In Robb’s essay, “Blood, Milk, Poison and Soil”, she writes that,

Robinson’s fascination with the witch coincides with the rise of the figure of the witch as a feminist symbol in contemporary culture – the most dangerous woman in history. The etymology of the word ‘witch’ comes from the German hexe for fence, as witches were considered to be fence-riders, figures that live on the border between two things – the human and divine, and the human and the demonic – and dwell between the conscious and unconscious.[3]

“Blood, Milk, Poison and Soil” also draws out the artist’s chronology–a tried-and-true methodology for the monograph–with the eye of a curator. The carefully traced material and conceptual transitions between distinct bodies of work galvanise Robinson as a storyteller, such as her 2015 exhibition One to rot and one to grow marking ‘…a thematic shift…from death to resurrection, that was echoed chromatically and tonally, with the muted boiled wool [of Some to the stone (2012) and Pinch Wood (2013)] in favour of gold and pink silks and ribbons.’[4]

Taking the artist’s view, Taylor (who was once Robinson’s student) drills down into the specific alchemy involved in transforming research into form, and therefore compresses the time and space of Robb’s chronology and Robinson’s oeuvre. It is Kent’s vignettes that expand it once more. Another kind of perverse material reversal, Kent’s writings function as ‘intuitive extractions’ of Robinson’s visual works.[5] In an opening gambit, Kent’s poem, titled after Robinson’s baba-yaga-esque Structure for navigating an unknown afterlife (2016), traces a cycle of beginning and ending and beginning again that keeps the wheel of life–and the wheels of Robinson’s practice–turning: ‘…there is no sleep there is only what there is only death-bed cradle-cot… no longer blood no longer breath no longer life no longer death.’[6] Notably, despite Kent’s success as a novelist and author, Julia Robinson is the first time Kent’s poetry has been published.[7]

In early August, on the eastern side of Adelaide, GAGPROJECTS announced this year’s SALA exhibition as their last. The commercial gallery in Kent Town, directed by Paul Greenaway OAM, has since closed their space to the public and turned towards art consultancy. It is a notable book end, not just because the gallery has been operating for 32 years and offered a multitude of Australian artists opportunities to exhibit, to be seen and collected (including Robinson), but also because SALA Week–as it was first known, 26 years ago–was founded by Greenaway, following discussions with fellow gallerist Sam Hill-Smith.[8] The inaugural SALA monograph was Annette Bezor, authored by Richard Grayson. These early machinations are traced across the Artlink archive and capture the substantial growth and contributions to the South Australian art scene of these now-institutions. The inaugural 1998 SALA Week exhibitions were held across 42 venues, which doubled the following year, and now unfolds as a month-long affair spread over 700 venues and featuring more than 10,500 artists.[9] Likewise, Annette Bezor now appears a slim 72 pages compared to the handsome, richly illustrated and speculative tome that is Julia Robinson.

Footnotes

- ^ Countess Report 2022, eds. Miranda Samuels and Shevaun Wright (20 April 2024), PDF, 7

- ^ Leigh Robb, “Blood, Milk, Poison and Soil,” in Julia Robinson (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2024),15

- ^ Robb, Julia Robinson, 34

- ^ Robb, Julia Robinson, 45

- ^ Hannah Kent, “Episode 47 / Julia Robinson, Leigh Robb, Hannah Kent, Jess Taylor,” 27 August 2024, in SALA Podcast, podcast, 1:05:37

- ^ Hannah Kent, “Structure for navigating an unknown afterlife,” in Julia Robinson, 11

- ^ Kent, SALA podcast.

- ^ Wendy Walker, 'Paul Greenaway: Energy Synergy', Artlink 22:3, September 2002.

- ^ SALA Festival, email with author, 2 September 2024.