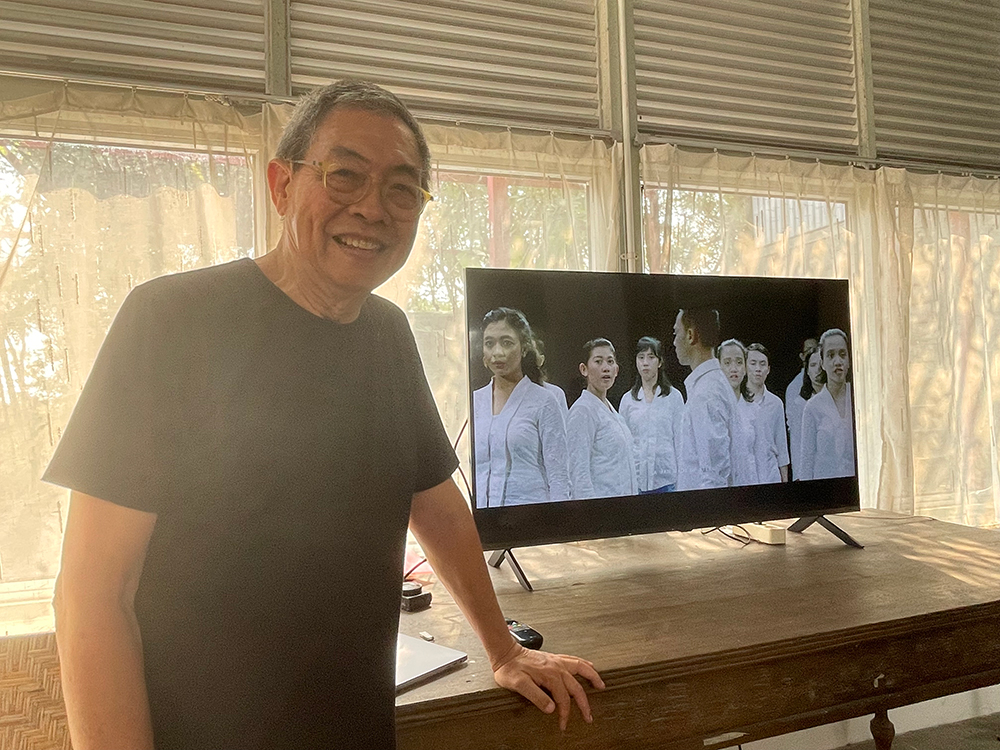

It was sometimes discomfiting to think of ourselves as a busload of cultural tourists, but we were. We had a name: the Australia Indonesia Art Forum, or Indonesian Art Study Tour 2024. In Yogyakarta, midday, day seven of ten, we climbed the wide concrete steps to the modernist lines of FX Harsono’s split-level studio comprising a high-ceilinged workspace-cum-gallery, an open-plan meeting area and an elevated office and library.

An icon of Indonesia’s contemporary art world and a leader of its shifting discourse inside and outside its institutions, Harsono assumes the role of elder/master, artist/educator and mediator/host with ease. His first question as we landed on the threshold was to ‘any Adelaide people’ who might have seen his work Nama (2019) screening at Samstag Museum of Art. None had.

A large roller-door allowed the heavy air to enter the building with us—the willing mob moving across the Indonesian cultural terrain at a clip, from Bali through Jakarta and Central Java to wrap up at ARTJOG 2024. As a group, we mostly rolled with—but occasionally grappled with—the ‘compressed delivery mode’ of our trip, as if speed-dating a wide cast of contemporary art types in varying states of play, place and tradition. At Harsono’s, as in numerous art stops, we gathered around the artist, thirsty for bottled water and insights into the art around us.

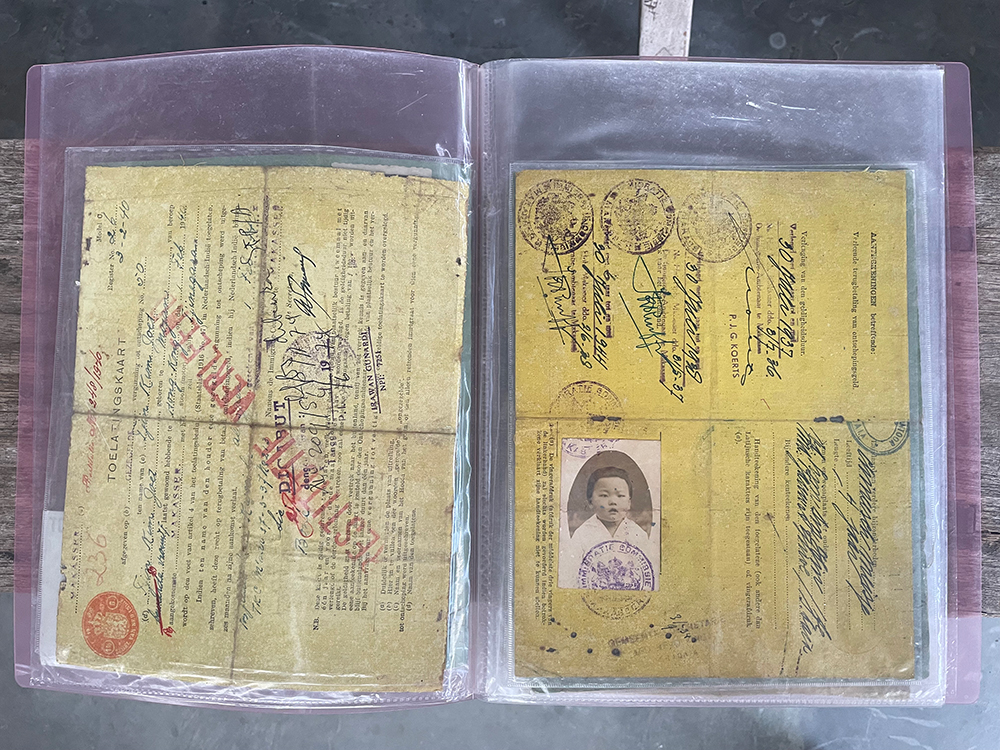

These included Shadow of Identity (2024), a syncretic altarpiece in which a horizontally scrolling red neon reads SHADOWS OF POWER OVERIDENTITY AND CULTURE – LET THEM DETERMINE THEIR OWN PATH / BAYANG-BAYANG KEKUASAAN DI ATAS IDENTITAS DAN KEBUDAYAAN – BIARKAN MEREKA MENENTUKAN JALANNYA SENDIRI. Nearby, a set of pinned works on paper drawn from Harsono’s family records embellished archival photographs lifted from the pervasive Chinese Indonesians Identity Cards. Until the post-Suharto era, these were forcibly required and difficult to acquire even when sovereignty was established across generations. A young Chinese female curatorial student (joining the group from Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok) avidly leafed the plastic folder of photocopied ID documents as if searching for someone.

Through the corrugated doorway, a breeze lifted the long vertical scrolls of Pilgrimage to History (2010–17), memorialised in the 2013 film of the same name. The drawings are rubbings of Chinese calligraphy, probably made in red ink but giving the effect of rosy floral tributes for those not literate in Chinese characters. We learnt that the work was taken from embossed text on marble memorials listing the names of Chinese Indonesians murdered and buried in unmarked, mass graves during the fight for independence after World War II, and again following massacres of alleged Chinese communists and their sympathisers in 1965 and afterwards.

This recuperative intergenerational project is ongoing, and the historic and contemporary persecution of Chinese Indonesians is a recurrent trauma and central theme in Harsono’s work, especially in the last quarter-century. This personal turn was amplified following events of 1998 when Suharto’s authoritarian New Order regime came apart—wreaking wide-reaching damage, from riots and arson attacks on Chinese Indonesian homes and businesses to the rape of Chinese Indonesian women. As a champion of social, collective activism, Harsono felt a sense of lost faith.

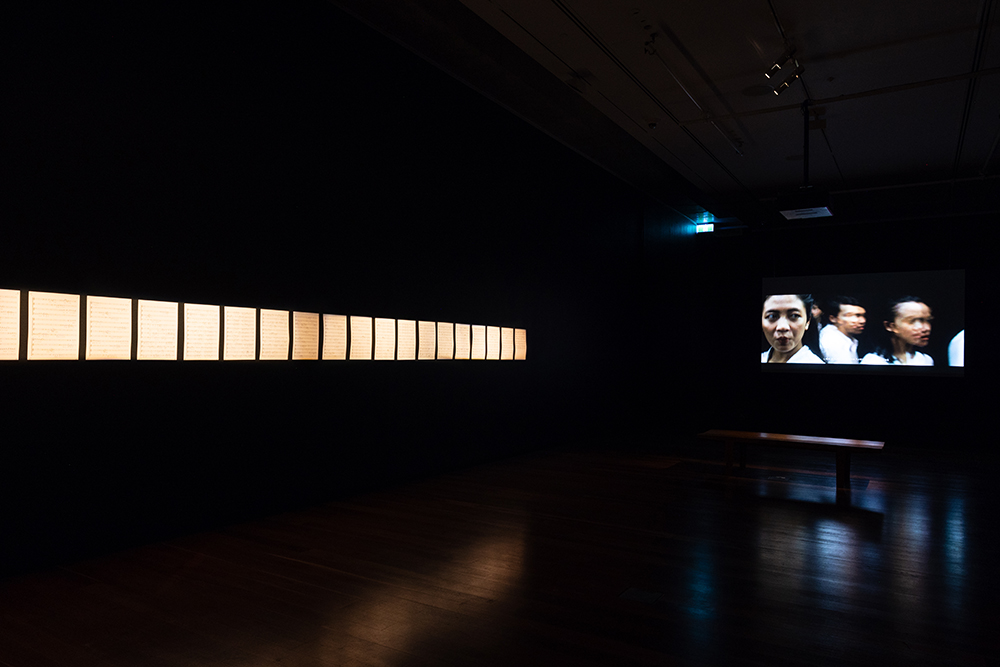

We watched Nama on a television monitor while eating lunch, its choral soundtrack accompanied by Harsono’s interjections and the play of sunlight across metal louvres. I imagined the film’s presentation at Samstag, the large format moving image, the space reverently dimmed, the liturgical score installed alongside the screen and lit like medieval manuscripts, with all the care of contemporary curating. Whatever the setting, Nama’s seductive choreography and soundscape contradicts its disturbing narrative: the recurrent chant of the repressed Chinese birth name, sung by a student choir from Atma Jaya University, recounting and thereby subtly recanting the Indonesian law of 1966 which forbade the use of Chinese names. (Siuli Tan’s excellent essay “FX Harsono: NAMA”, written for the Samstag exhibition catalogue, sheds further light on the film and its longer shadows.) It’s a history that Australians (who know their history) sit uncomfortably with, witness to a nation state which attempts to crush a people by banishing the mother tongue (and worse), systematically endeavouring to erase deep-held traditions and cultural identities.

After a week on the road and countless call-ins, even the most fastidious among us had lost some track of time, place and face, skipping through the full range of artist’s studios, collectives, galleries and shopfronts. They ranged from close quarters in family compounds, with gardens and temples adjoining small domestic spaces or workshops, to expansive architecturally designed white-cube galleries housing major collections, and slick commercial enterprises in affluent hilltop suburbs. In archives and universities, back rooms and bookstores, Asia Pacific Triennial catalogues and Queensland Art Gallery crates offered residual markers of cultural exchange between our two countries. The material and conceptual frameworks ranged just as widely, though much of the art is shot through with the tough social and political realities of living under successive oppressive regimes.

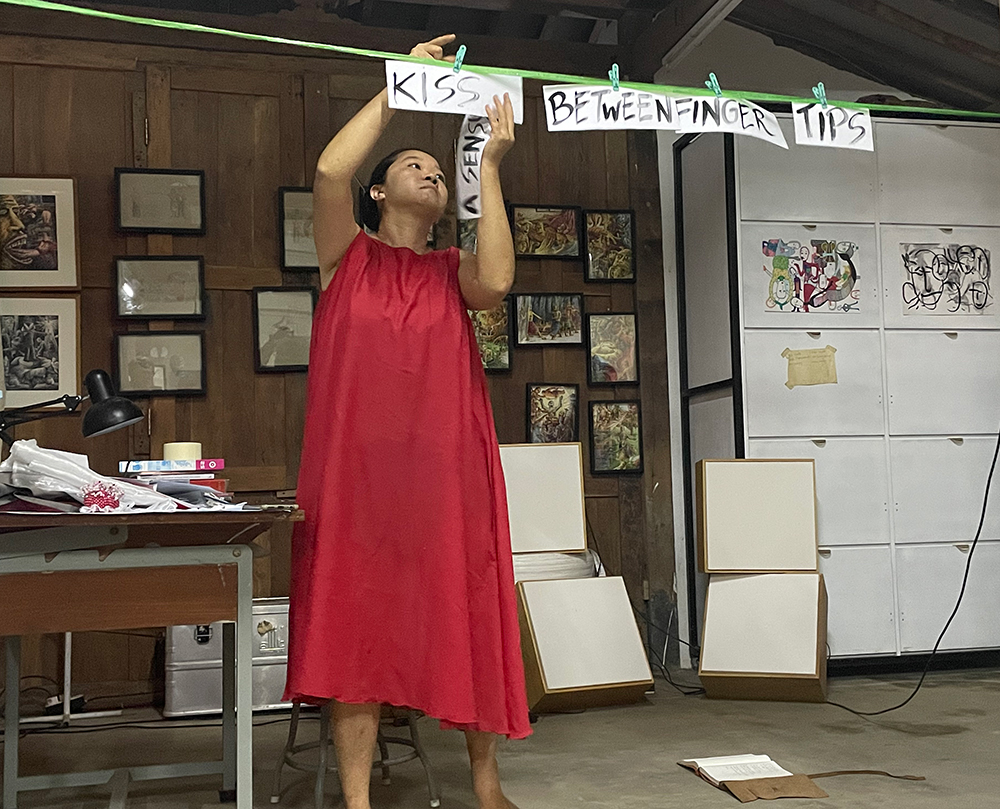

The previous day, following an exhaustive tour of the OHD Museum and private collection in Magelang, we gratefully received the evening hospitality of artists Agnes Christina and Popok Tri Wahyudi, whose interfaith marriage poses a challenge to Indonesian law. Working across storytelling formats Christina’s performance of The Knot (2024–) acted as an unannounced mindfulness exercise, its silent opening gestures bringing calm and focus to the frayed travellers. The red, black and white palette (garment, text, paper) and Christina’s humorous, tempered narration of her experience as a young Chinese Indonesian woman artist struck a potent chord and a sobering note. Like so many times over, we were reminded of our privilege and freedoms, while becoming ever so slowly the wiser to Indonesian artists, their practices and realities. And then we were back on the bus.